A Coach’s Guide to Breaking Through Self-Limiting Beliefs in Distance Runners

The snow was coming down sideways, the kind of February afternoon in New Hampshire where the wind makes the windows rattle and you’re grateful to be inside. I sat across from one of my runners—let’s call her Clara—talking about her cross country season and mapping out what track might look like.

We talked splits. We talked workouts. We talked about the team, about who was doing what this winter, about her goals for the upcoming season.

And then we talked about what really mattered.

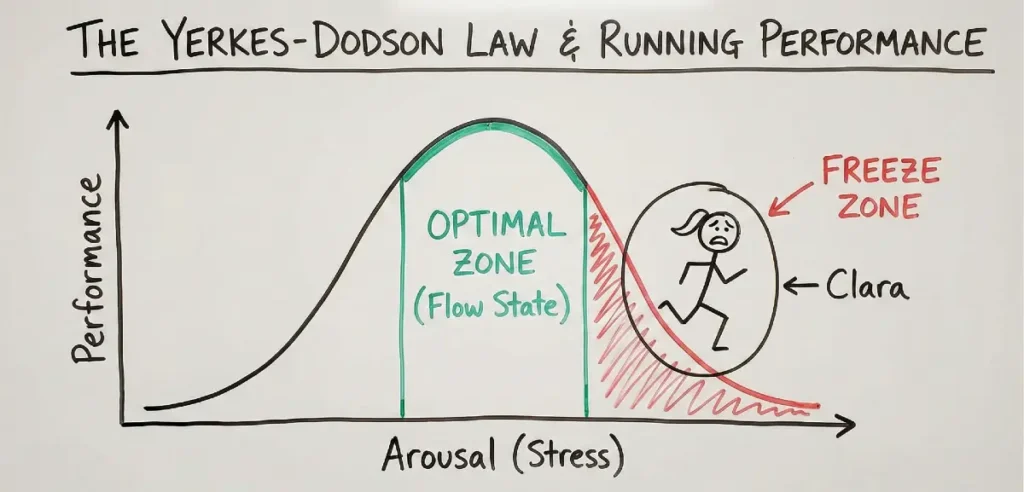

I mentioned that racing brings a specific kind of anxiety—the kind that makes your body scream for an escape route. Fight, flight, or freeze. I’ve seen all three responses in my 25 years of coaching. Some kids fight through the pain and push harder. Some kids take flight and just bail on the workout mentally. And some kids freeze.

Clara is a freezer. 🥶 Ice cold.

She’d lock up midrace, her stride shortening, her arms tightening, her face going blank. Sometimes she’d step off the course entirely feeling dizzy or sick to her stomach. Other times, she’d just fade so dramatically that you’d never mistake her for one of the varsity scorers, even though her workout times said she should be.

She was a practice hero who couldn’t translate it to race day. Just good enough to be a 7th runner, but never even challenging 6th.

I asked her why she thought this kept happening. What was she feeling when she started to shut down?

She looked out the window at the snow for a long moment. Then she said it:

“Coach, honestly? I’d rather be the fast one in the slow group than the slow one in the fast group.”

And there it was.

The sentence that explains why some talented athletes plateau while others with less natural ability soar past them. The admission that reveals the massive hidden iceberg lurking beneath the surface—an iceberg made up of friendships, relationships, expectations, self-confidence, and external pressure.

If you coach long enough, you’ll hear some version of this confession. It might come after a disappointing race. It might slip out during a workout when you ask why they’re holding back. It might show up in a text message at 11 PM when the athlete finally finds the courage to be honest just hours before the big race. Or it might literally happen at the starting line of the divisional championship race. I’ve seen it all.

So, when you hear it, you need to recognize it for what it is: a massive red flag disguised as self-awareness.

The Psychology of Performance Anxiety: Understanding Self-Handicapping

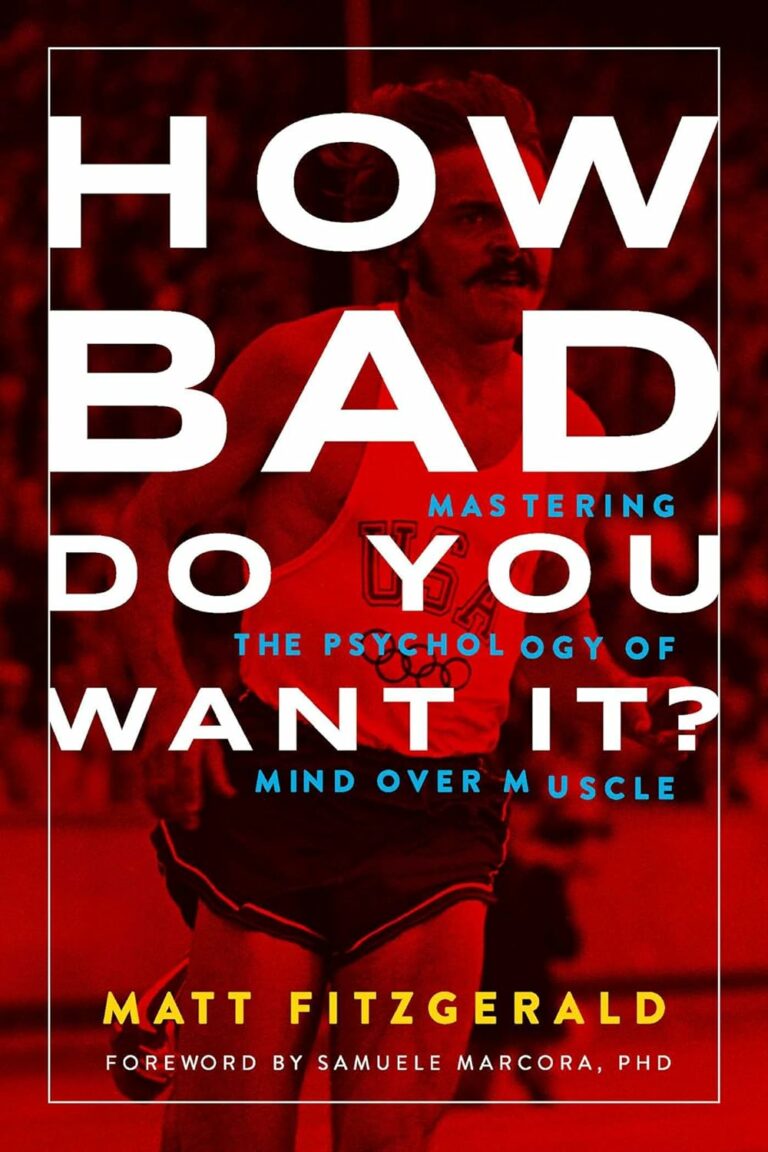

Let me put on my armchair sports psychologist hat for a moment, because understanding the “why” is critical before we can address the “how.”

What this athlete is really saying is that they fear negative social evaluation—they’re terrified that others will view them as a failure if they can’t keep up with faster runners. When athletes focus on what they don’t want to happen rather than what they want to achieve, it becomes nearly impossible to perform with confidence and trust in their abilities.

This mindset has a name in sports psychology: self-handicapping. It’s when athletes engage in behaviors that allow them to attribute failure to external factors rather than to their abilities. By choosing to train with slower runners, your athlete is creating a pre-made excuse. If they don’t improve, well, it’s because they weren’t training with fast enough people. It protects their ego, but it destroys their potential.

Here’s what the research tells us:

Athletes with growth mindsets analyze defeats for improvement opportunities, while those with fixed mindsets interpret losses as evidence of limited ability. Clara has adopted a fixed mindset—she believes her current speed represents who she is rather than where she is right now.

The fear itself causes athletes to play timidly and hold back, focusing more on avoiding mistakes than on performing freely and confidently. And here’s the killer: behavioral self-handicapping is negatively correlated with actual athletic performance. In other words, this strategy doesn’t just limit growth—it actively makes athletes slower.

The One-on-One Conversation: How I Address It

When an athlete admits this to me, I don’t lecture. I don’t get frustrated. Instead, I ask questions. Good questions.

Me: “Tell me more about that. What are you afraid will happen if you train with faster runners?”

Usually, they’ll say something like: “I don’t want to be the one holding everyone back” or “I don’t want them to think I’m slow.”

Me: “So you’re worried about what they’ll think?”

Athlete: “Yeah.”

Me: “Here’s the thing I’ve learned in 25 years of coaching: The fast kids aren’t thinking about you during the workout. They’re thinking about themselves, their splits, their form. And you know what? If they ARE judging you? They’re likely judging everything and everyone- including themselves.”

I let that land for a second, then continue:

Me: “Let me ask you something different. When you’re running with the ‘slow group,’ are you getting faster?”

This is where they usually go quiet, because they know the answer.

Me: “You can’t become what you don’t practice being. If you always train with people you can beat, you’ll always BE someone who can only beat those people. But if you train with people who push you past what’s comfortable and easy, you become someone stronger.”

Then I hit them with the hard truth:

Me: “Right now, you’re making a choice. You’re choosing comfort over growth. You’re choosing your ego over your potential. And that’s okay—it’s your choice to make. But I need you to own it. Don’t tell me you want to run a sub-20 5K and then refuse to train with the sub-20 kids. Don’t tell me you want to really get better this season and then hide in the middle of the pack during workouts, or make excuses because it feels safer.”

The Growth Mindset Intervention

Almost every great athlete has a growth mindset. My job is to help athletes transition from “I can’t” to “I haven’t yet.” Here is the 4-step protocol:

1 Reframe Failure as Data

I have athletes keep a workout journal. After every hard session, they record three specific things:

- What went well

- What I learned (Where was my limit today?)

- What I’ll adjust next time

2 Set Process Goals

Outcome goals (like “Beating Sarah”) are uncontrollable. We replace them with controllable process goals:

- ❌ Outcome: “Don’t get dropped.”

- ✅ Process: “Hit the specific split times for the first 2 reps.”

- ✅ Process: “Keep arms from crossing the body when tired.”

3 Controlled Exposure

We don’t throw them into the deep end. We build “unshatterable belief” through a progression:

- Week 1-2: Warmups/Cooldowns with fast group.

- Week 3-4: First half of the workout only.

- Week 5-6: Complete the full workout (even if you fade).

- Week 7+: Find your place in the pack.

4 Public Commitment

I announce the workout groups out loud each day. This creates immediate social accountability.

It is much harder to hide in the “safe” group when the whole team knows you are supposed to be pushing with the fast pack. We make bravery the standard, not the exception.

The Social Complexity: Why This Hits Different for Teenage Girls

Before we talk about the team-wide approach, I need to address something that’s often the elephant in the room: this issue affects teenage girls differently, and more acutely, than it affects boys.

I’ve coached both boys and girls for over two decades, and I can tell you unequivocally that the social stakes of athletic performance are significantly higher for girls. This isn’t just my observation—it’s backed by extensive research on adolescent female development and sports participation.

The Social Minefield of Female Athletic Performance

Here’s what I’ve learned: for many teenage girls, their athletic performance doesn’t just affect how they see themselves—it fundamentally shapes their social standing, their friendships, and their sense of belonging in ways that boys simply don’t experience to the same degree.

“As one school counselor—a former competitor herself—put it, high school is essentially a real-life game of Survivor. The goal isn’t just to win; it’s to make sure you don’t get voted off the island.”

According to data from the Women’s Sports Foundation, by age 14, girls drop out of sports at two times the rate of boys. A primary factor? Social stigma and body image issues.

When a girl chooses to train with the fast group and gets dropped, she’s not just dealing with physical failure—she’s navigating a complex web of social consequences:

The “Backhanded Compliment” Dynamic

One female track athlete described it perfectly in a recent study: “There have been a few individual races this season where I kept beating them and I noticed they got annoyed and a little jealous. They would make backhanded compliments; they weren’t happy for me…I was making them look bad so they wouldn’t talk to me.”

This is the reality: when girls outperform their peers, they sometimes face social punishment. The faster girl becomes threatening. Friendships become conditional. The locker room gets quiet.

And here’s the brutal irony: if she holds back to stay with the slower group, she preserves the friendships but sacrifices her potential. If she pushes ahead, she might lose those relationships entirely.

The Body Image Battlefield

Gender stereotypes serve as a significant barrier to physical activity participation for adolescent girls.

Girls are already navigating impossible standards about how their bodies should look. Add athletic training to that mix—the muscular legs, the broader shoulders, the lower body fat percentage—and you’ve created a minefield. Some girls fear that becoming “too athletic” will make them less feminine, less attractive to peers, or subject to ridicule. While others fear that they don’t “look like runners” and therefore cannot be good at it.

I’ve had girls tell me they don’t want to lift weights for fear of getting too big. I’ve had parents express concern that their daughter is too thin from running. And, worst of all, I see a lot of girls that fear food as a fuel. This is the reality we’re working with. We want healthy student athletes. Healthy isn’t a look, it’s a lifestyle.

Why the Fear Is More Than Just Fear

During adolescence, friendships provide deep emotional connections offering companionship, validation, and a sense of belonging that helps adolescents navigate challenges, while supportive friendships are related to positive mental health and peer conflict is associated with heightened risk of mental health problems.

When a teenage girl says “I’d rather be the fast one in the slow group,” she’s not just being lazy or lacking confidence. She’s making a calculated social decision based on very real consequences she’s observed or experienced.

She’s seen what happens to the girls who push too hard:

- They get isolated at team dinners

- They don’t get invited to the social gatherings outside of practice

- They’re labeled as “too intense” or “too competitive”

- Their successes are minimized or attributed to “just being naturally gifted”

She’s navigating questions that boys rarely face:

- Will my friends resent me if I get too fast?

- Will boys think I’m too aggressive?

- Will I have to choose between being good at running and being liked?

- If I fail trying to keep up with the fast girls, will everyone think I’m a fraud?

The Coach’s Dilemma: Friendship Groups vs. Training Groups

Here’s where it gets really complicated for us as coaches. Research shows that peer dynamics in team sports are better able to sustain interest and motivation than coach relationships alone, with athletes stating that relationships with peers got them through hard times and kept them interested when ready to quit.

In other words: FRIENDSHIPS ARE THE REASON many girls stay in the sport.

So when we push a girl to leave her friend group to train with faster runners, we’re not just asking her to get uncomfortable physically—we’re asking her to risk the very thing that makes the sport enjoyable for her.

This is why the “just do it” approach doesn’t work as well with girls. We have to acknowledge and work WITH the social dynamics, not against them.

What Actually Works: A Different Approach for Girls

Based on both research and my experience, here’s what I’ve found effective:

1. Create Mixed Training Opportunities

Instead of rigidly dividing the team by pace, I create workouts where different groups naturally overlap:

- One group does 8 x 800m

- One group does 6 x 800m

- Both groups start at the same time

This allows all the girls to train alongside each other without the pressure of completing the entire session. Some can experience what it’s like to run with faster girls without the all-or-nothing commitment.

2. Build Bridges Between Groups

I intentionally pair girls from different training groups as workout partners for warm-ups, cool-downs, and easy runs. This prevents the formation of exclusive social cliques and helps girls see that they can have friends across performance levels.

3. Reframe Competition as Collective Achievement

Girls respond better to team goals than to individual rankings. Instead of posting times that create a hierarchy, I track team improvement:

- “Last week, our varsity averaged 21:30 for 5K. This week we averaged 21:15. That’s what we call getting better.”

- “Emma dropped 20 seconds, Sarah dropped 15, and Mia ran her first sub-22. That’s three PRs in one race—we’re building something here.”

- Create a fun award like the Salty Shoe and award it to a member of the team that had an outstanding performance based on their own progression

4. Address the Social Dynamics Explicitly

I talk about this stuff openly with the team:

“Listen, I know that in middle school and early high school, sometimes being really good at something—especially sports—can make you feel like you have a target on your back. I know some of you have experienced friends who got weird when you beat them. I know some of you have been accused of being ‘too competitive’ or ‘too intense.’

Here’s what I want you to know: on this team, we celebrate each other’s success. If you can’t be happy for your teammate when she PRs, you don’t belong on this team. If you make backhanded comments or give someone the silent treatment because they ran faster than you, we’re going to have a conversation.

And if you’re holding back because you’re afraid your friends will resent you—I want you to know that real friends don’t resent your success. They celebrate it. And if the people around you can’t handle you becoming the best version of yourself, those aren’t your people.”

5. Leverage the Power of Female Role Models

Peer and family support, especially from mothers, increases girls’ feelings of competence, enjoyment of activities, and persistence with sports, while teasing particularly related to physical appearance was cited as a strong concern among girls who left sport.

I bring in former athletes—college runners, or even just successful alumni—to talk to the team about navigating these exact dynamics. Hearing from someone who’s been through it carries more weight than anything I can say.

The Hard Conversation with Parents of Daughters

Parents of girls need to hear this too, because they’re often unintentionally reinforcing the very dynamics we’re trying to break.

When I meet with parents at the beginning of the season, I say this:

“Your daughter is navigating something your sons probably won’t experience to the same degree. She’s in a sport where being too good, too competitive, or too intense can actually hurt her socially. That’s the reality.

Some of you might be tempted to tell her to ‘just focus on the running and not worry about what other people think.’ But that’s easy for us adults to say. For a 15-year-old girl, her peer relationships literally feel like life or death sometimes. Her brain is wired to prioritize social connection.

So here’s what I need from you: don’t minimize the social stakes for her. Don’t tell her friendships don’t matter or that she should just ignore the drama. Instead, help her see that there’s a difference between friends who support her growth and friends who need her to stay small so they can feel comfortable.

Help her find the courage to choose the first kind.”

When to Recognize It’s About Safety, Not Comfort

Here’s an important distinction I’ve learned to make: sometimes a girl’s reluctance to train with faster runners isn’t about comfort—it’s about genuine social or emotional safety.

If a girl is being bullied, ostracized, or subjected to targeted cruelty by the faster group, my job isn’t to force her into that environment. My job is to address the toxicity first.

I watch for these warning signs:

- Social media exclusion or negative posts about certain athletes

- Deliberate attempts to make a runner feel unwelcome during workouts

- Comments about body size, eating habits, or appearance

- Formation of exclusive cliques that actively exclude others

When I see this stuff, the conversation shifts from “You need to be tougher” to “We need to fix the team culture.” Because no athlete—male or female—should have to choose between their athletic development and their emotional well-being.

The Team Meeting: Setting the Culture

This isn’t just an individual problem—it’s a team culture issue. So I address it with everyone.

Here’s what I tell the whole team at the beginning of the season:

“Listen up. We have runners of different abilities on this team, and that’s not just okay—it’s awesome! But I need to make something crystal clear: this team does not tolerate mediocrity disguised as humility.

If you’re capable of running with the varsity group but you choose to hang back with JV because it’s more comfortable, you’re not being humble—you’re being selfish. You’re robbing yourself of growth, and you’re robbing the slower runners of their chance to lead their own group and grow themselves.

On this team, we run where we belong based on fitness, not based on where our friends are. And if you’re brave enough to run with people faster than you—even if you get dropped—we will celebrate that courage. Because that’s how champions are made.”

Then I make it tangible:

“We’re going to have three workout groups: Red, White, and Blue. Blue is the fastest. White is developing. Red is in between. But here’s the thing—these groups are fluid. If you’re in White and you think you can hang with Red, I want you to try. If you make it through the workout, you’re in Red next time. If you don’t, you go back to White and we try again in two weeks.”

The language of growth, if cultivated routinely, finds its way into other areas of life, and creating space between an event and one’s response allows for intentional use of growth-oriented language rather than fixed, negative methods.

I also address the fast kids directly:

“And for those of you in the Blue group—your job isn’t just to run fast. Your job is to PULL people with you. If someone’s struggling to hang on, you encourage them. You tell them they’re doing great. You do NOT drop them intentionally and then talk about how slow they are afterward. Leaders lift. Always.”

The Parent Conversation: Managing Expectations

Parents are harder than athletes sometimes, because they’re protective. They don’t want to see their child struggle. They don’t want to see them get dropped in workouts or finish last in races.

So when a parent comes to me concerned about their daughter “being pushed too hard,” sometimes it’s because their child came home upset because they couldn’t keep up with the fast group.

Here’s how I handle it:

“I appreciate you coming to me with this concern. Let me share what I’m seeing. Your daughter is talented—really talented. But right now, given the choice, she’s operating in her comfort zone. She’s training with people she can keep up with, which feels good in the moment but limits her long-term growth.

Think of it like school. If your daughter is capable of honors math but chooses regular math because honors seems ‘too hard,’ would you support that choice? Probably not, because you know she won’t reach her potential that way.

Running is the same. The discomfort she’s feeling? That’s not injury. That’s not overtraining. That’s growth. Her body is adapting and getting stronger in the process. My job as her coach is to help her navigate that discomfort safely while pushing her toward her potential.”

Then I give them the research:

Failure creates opportunity to learn and grow, and looking at situations from both worst-case and best-case scenario perspectives helps athletes see the benefits of pushing themselves beyond their comfort zone.

“The worst-case scenario? She gets dropped in a workout and has to run the cooldown by herself. That’s uncomfortable, but it’s not dangerous.

The best-case scenario? She discovers she’s capable of far more than she thought. She makes varsity. She earns a PR. She becomes a leader on this team.

Most parents get it once you frame it this way. The ones who don’t—well, that brings me to my next point.

When to Walk Away: Knowing Your Limits

Here’s the hard truth that took me years to accept: you can’t coach someone who doesn’t want to be coached.

Over 25 years, I’ve learned that high school distance runners generally fall into four categories:

The Pretender is the one who will cause you and your team the most headaches. And here’s what I’ve learned: you can’t fix someone who doesn’t think they’re broken.

I give them one season. Maybe two if I’m feeling generous.

I have the conversations. I offer the support. I create the opportunities. I adjust the training. I meet with the parents. I try the carrot. I try the stick. I try everything in between.

But if by the end of that season they’re still choosing comfort over growth, still making excuses instead of adjustments, still demanding attention without putting in effort—I stop investing my finite time and energy trying to change them.

Why?

Because I have 20 other athletes who DO want to get better. Athletes who show up even when it’s hard. Athletes who ask “What can I do to improve?” instead of “Why do I have to do this?” And spending 80% of my coaching bandwidth trying to convince one athlete to care means I’m neglecting the athletes who already do.

So eventually, I have this conversation:

“Listen, I think you’re capable of great things. I really do. But I can’t want it for you more than you want it for yourself. I can’t care about your running more than you care about it. The door is always open if you change your mind—it genuinely is. But right now, I need to focus my energy on athletes who are ready to do the work.”

And then I move on.

It’s not giving up. It’s recognizing that some lessons can only be learned through personal experience. Sometimes an athlete needs to watch their teammates improve while they stagnate before they’re ready to make a change. Sometimes they need to see what they’re missing before they’re willing to reach for it.

And that’s okay. That’s part of growing up.

The Wrong Reasons

Here’s another truth worth naming: some kids are running for the wrong reasons.

Maybe they’re running because their parents were runners and expect them to be too. Maybe they had success in middle school and are trying to relive past glory rather than create new success. Maybe they think being on the team will look good on a college application, so they’re just checking a box.

But here’s the thing about high school distance running: if you don’t genuinely love it—or at least love something about it—you’re not going to make it.

This sport is too hard. The workouts are too demanding. The weather is too brutal. The early mornings and late afternoons are too sacrificial. The soreness, the fatigue, the mental battles—none of it is worth it unless you actually want to be there.

You don’t have to love every workout. You don’t have to love every tempo run or hill repeat or freezing November morning. But you do need to love something about running—the feeling of getting stronger, the camaraderie of the team, the satisfaction of a PR, the rhythm of your feet on the trail, the clarity it brings to your mind.

If you can’t find that love somewhere in the sport, then distance running probably isn’t for you. And that’s not a moral failing. It just means you should find something else that lights you up.

My job as a coach isn’t to convince you to love running. It’s to help athletes who already have that spark turn it into a fire.

And for the athletes who don’t have that spark? I hope they find it somewhere else. Because every kid deserves to find the thing that makes them come alive—it just might not be running.

The Long Game: What This Is Really About

Look, this conversation isn’t really about running. It’s about life.

The athlete who chooses the slow group because it feels safer is the same person who will choose the easy major in college because the hard one is “too stressful.” They’re the same person who will stay in a dead-end job because looking for a better one is “too risky.”

When coaches refer to the life lessons learned through sport, growth mindset might be one of the most powerful, and cultivating this mindset often requires creating space between an event and one’s response to it.

Our job as coaches isn’t just to make kids faster. It’s to teach them that discomfort is not the enemy—mediocrity is.

It’s to show them that the only way to discover what you’re capable of is to try things that scare you.

It’s to help them understand that being the slowest person in a fast group is infinitely more valuable than being the fastest person in a slow group, because growth happens at the edge of your ability, not in the middle of your comfort zone.

My Challenge to You (And Your Athletes)

If you’re a coach reading this and you have an athlete like Clara on your team, here’s what I want you to do:

1. Have the conversation. Don’t avoid it because it’s uncomfortable or because you’re worried about hurting their feelings. The discomfort of an honest conversation is nothing compared to the regret of wasted potential. This is exactly the kind of moment we signed up for as coaches—we’re teaching kids to embrace hard truths, not run from them.

2. Set clear, non-negotiable expectations. Tell them what you expect from them. Make it clear that trying—genuinely trying—to train with faster runners is a requirement, not a suggestion. They don’t have to complete every interval with the fast group. They don’t have to keep up the entire workout. But they do have to show up at the start line of the workout willing to chase discomfort.

3. Celebrate courage, not just outcomes. When they get dropped trying to hang with the fast group—and they will get dropped—praise them for trying. Make it abundantly clear that courage is valued on your team. Create a culture where attempting something hard and failing is celebrated more than playing it safe and succeeding.

4. Be patient, but set boundaries. Give them time to adjust. Real mindset change doesn’t happen overnight. But don’t waste an entire career trying to convince someone who refuses to be convinced. One season, maybe two—that’s your window. After that, you’re not helping them by continuing to push. You’re just enabling the avoidance.

5. Know when the issue is bigger than running. If you suspect anxiety, depression, or other mental health challenges are at play, loop in school counselors, parents, or sports psychologists. Sometimes “I’d rather be the fast one in the slow group” isn’t about training philosophy—it’s a symptom of something deeper that requires professional support.

And if you’re an athlete reading this and you recognize yourself in Clara’s story—if you’ve ever felt like quitting before a race, or found yourself holding back in workouts because you’re afraid of what failure might mean—here’s my challenge to you:

Just try it. Once.

One workout. That’s all I’m asking.

Run with the fast group. Get dropped if you have to. Struggle if you must. Feel that burning in your legs and that voice in your head telling you to quit.

But see what it feels like to chase something beyond what’s comfortable.

See what it feels like to cross a finish line knowing you gave everything you had, even if “everything you had” wasn’t enough to keep up.

See what it feels like to walk back to the start knowing you were brave.

Because here’s what I’ve learned after coaching hundreds of athletes over 25 years:

The runners who make me the proudest aren’t the ones who were naturally fast.

They’re the ones who were terrified but showed up anyway.

They’re the ones who got dropped in workouts, asked questions about what went wrong, learned from their mistakes, and showed up ready to try again the next day.

They’re the ones who chose discomfort over comfort, growth over safety, and potential over ego.

Those are the athletes who don’t just get faster.

They mature into people who understand that the only limits that truly matter are the ones they place on themselves.

They become adults who know how to face hard things, who understand that temporary failure is just part of the process, who inspire others through their example rather than their excuses.

They become the kind of people who, years later, will look back on their running career and say, “That sport taught me who I could become.”

And that—not the medals, not the PRs, not the college scholarships—is what this is really about.

So here’s my final question for you, whether you’re a coach or an athlete:

What are you going to do with this moment?

Are you going to keep playing it safe, staying comfortable, choosing the path of least resistance?

Or are you going to step into the arena, risk losing, and discover what you’re actually capable of?

The choice, as always, is yours.

But I hope you choose bravely.

Share this with a coach who needs it. Forward it to an athlete who’s ready to hear it.

Because this message could change someone’s season—or their life.