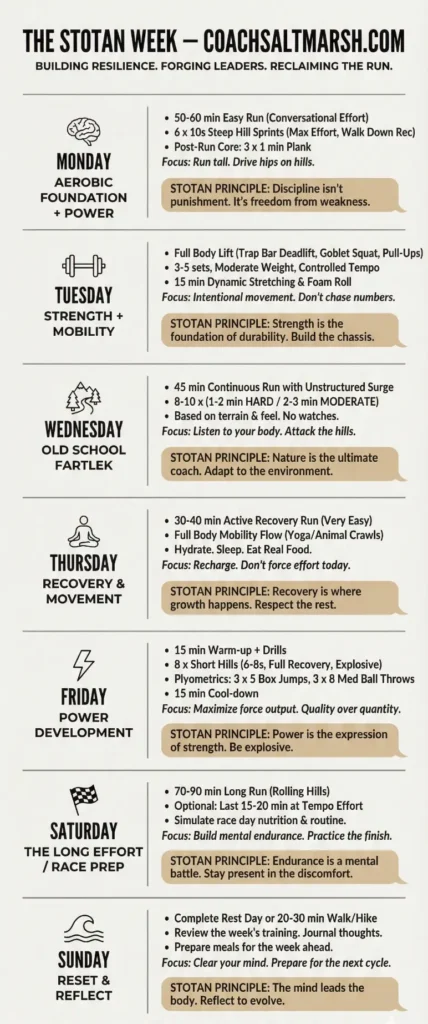

Why This Australian Madman Was Right About Everything

Grit Over Garmin: The Stotan Training Method

A Coaching Essay for High School Distance Runners

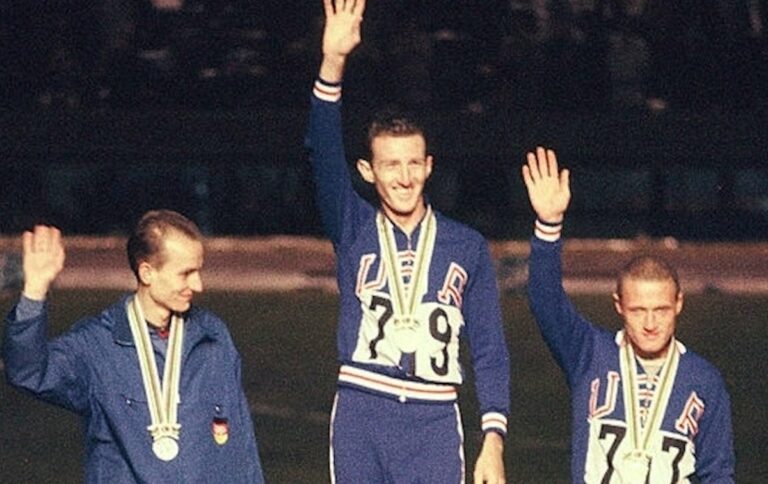

It’s 1960.

Herb Elliott—undefeated in every 1500m and mile race he ever ran—is charging up a 60-foot sand dune in Portsea, Australia. His coach, Percy Cerutty, is nearby, likely shouting something unfiltered like:

“BE A BEAST!”

Meanwhile, in New Zealand, Arthur Lydiard is carefully periodizing training cycles, building aerobic bases with scientific precision.

Both methods worked.

Both produced Olympic champions.

But only one of them makes you want to ditch your watch, leave the track, and run until something inside you changes.

If you’ve ever felt that modern distance training has become too sanitized—too safe, too dependent on data—Percy Cerutty deserves your attention.

This isn’t an argument against sports science.

It’s an argument for what science can’t measure.

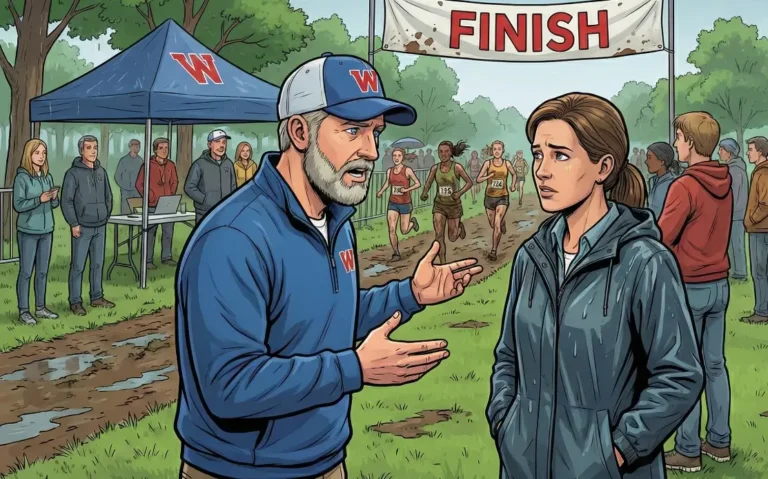

Because when your athletes are hurting with 800 meters to go at the State meet, physiology matters—but psychology decides the outcome.

Here’s what a “madman” from 1950s Australia can teach high school coaches in 2026.

1. The Stotan Philosophy: Training Athletes to Be Hard to Kill

Cerutty didn’t talk about mindset.

He talked about Stotan—a blend of Stoic and Spartan.

The Core Belief

Modern comfort makes athletes fragile. Great runners aren’t just fit—they’re resilient. Cerutty believed toughness had to be trained deliberately, not hoped for on race day.

Larry Myers, Cerutty’s own protégé, detailed exactly how the method developed “Whole Men”—athletes whose unshakable confidence came from enduring voluntary hardship—in his essential guide, Training with Cerutty.

What This Means for High School Coaches

You cannot build resilient racers in perfectly controlled environments.

The athletes who perform best in late October and November—cold, wet, windy, chaotic conditions—are not the ones who trained exclusively on a track with precise splits and ideal weather. That kind of resilience becomes especially valuable deep into the high school cross country season, when conditions are unpredictable and athletes are competing on accumulated fatigue.

They’re the ones who learned early that discomfort is normal—and survivable.

Practical Application

Once every week or two, schedule an “Old School” session:

- No watches

- No phones

- No earbuds

- No track

Find the hilliest, muddiest, least convenient terrain within 15–20 minutes of campus and run hard by effort.

The goal is not pace accuracy.

The goal is psychological durability.

You are teaching athletes:

- They can adapt when conditions aren’t perfect

- Effort matters more than numbers

- Confidence comes from experience, not data

Will this improve their Strava graphs? No.

Will it help them close hard races? Every time.

2. The Sand Dunes of Portsea: Strength Before Speed

Cerutty’s most famous training tool was the Big Hill at Portsea—a steep sand dune rising roughly 60 feet from the beach.

In the 1950s, he believed two things that most coaches ignored.

Strength Is Foundational

Running on sand forced powerful force production through a full range of motion. The unstable surface strengthened stabilizers that track running never touches.

This was resistance training—without a weight room.

Pain Is Trainable

Dune repeats hurt differently than track intervals. They combine muscular fatigue, cardiovascular stress, and psychological pressure. Athletes learn how to stay composed when everything hurts.

When Herb Elliott hit the final lap of the Olympic 1500m, it felt manageable—because Portsea had already shown him worse.

The High School Translation

You don’t need a sand dune.

Strength still precedes speed.

Hill Sprints (Early Base Phase)

- 6–8% grade

- 60–80 meters

- 6–8 reps at 90–95% effort

- Full walk-down recovery

Cue athletes to:

- Drive the hips

- Keep steps quick and powerful

- Maintain posture under fatigue

These are not aerobic hill repeats.

They’re neuromuscular power work that improves finishing speed and durability.

Cerutty understood—long before research confirmed it—that economy improves when athletes learn to apply force efficiently.

3. The Animal Model: Teaching Athletes How to Move

Cerutty rejected the passive “shuffle.” He studied animals—horses, lions—and emphasized relaxed power and efficient posture.

Three Stotan Movement Cues

- High Hips: Avoid sitting as fatigue sets in

- Pawing Action: Pull the ground backward, don’t slap it

- Relaxed Upper Body: Tension bleeds speed

Coaching Tip: Add animal movements (bear crawls, frog hops) to warm-ups. They reinforce core-driven movement and improve coordination without over-coaching mechanics.

4. Fueling the Athlete, Not the Appetite

Long before “clean eating” trends, Cerutty emphasized unprocessed foods. He believed athletes couldn’t recover—or stay healthy—on refined junk.

Keep It Simple

- Prioritize foods that spoil: fruits, vegetables, nuts

- Minimize refined sugars and ultra-processed snacks

For high school athletes, this isn’t about perfection.

It’s about reducing illness, improving recovery, and staying consistent during the season.

5. Strength Training: Why Cerutty Ignored the Fear

In Cerutty’s era, coaches worried lifting would make runners slow.

He disagreed—and time proved him right.

Simple, Effective Strength (2× Weekly)

- Trap Bar Deadlift: 3×5 (explosive intent)

- Box Jumps: 3×8

- Single-Leg RDLs: 3×10

- Medicine Ball Slams: 3×10

The goal isn’t hypertrophy.

It’s force production and injury resistance.

6. Coaching Identity, Not Just Fitness

This is Cerutty’s lasting lesson.

He didn’t just train bodies—he shaped how athletes saw themselves. That distinction—between managing workouts and shaping identity—is what separates programs that develop racers from programs that develop competitors.

When Herb Elliott raced, he didn’t wonder if he was ready. He knew—because he had already endured more than his competitors.

The Question for Modern Coaches

Are you building athletes who believe they can suffer longer than the field?

Because:

- GPS can’t measure courage

- Heart rate can’t quantify confidence

- Load management doesn’t create identity

Those things come from experience.

How High School Coaches Can Apply This Now

Train the Person

Talk openly about resilience and responsibility. Ask athletes who they want to be when things get hard.

Schedule Controlled Chaos

Once every two weeks, remove structure. Let effort guide the session.

Develop Power

Include sprints, jumps, and throws. Distance runners still need fast muscles.

Final Thought: The Dunes Are Everywhere

You don’t need Australia.

The dunes are:

- February hill days in the cold

- Early-morning lifts

- The last rep when legs are gone and excuses are loud

Percy Cerutty was called extreme.

But his athletes trusted him—and they won.

As coaching continues to chase better data and cleaner metrics, it’s worth remembering an old truth:

Greatness is built in discomfort. That belief should be woven into every part of your program, from preseason planning to how you define success on race day.

And no device will ever replace that.