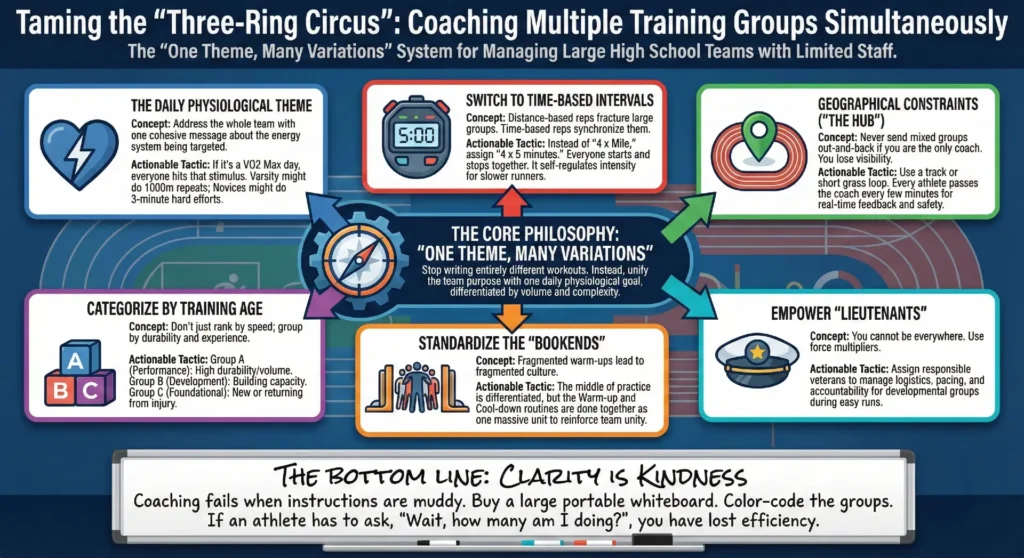

The Three-Ring Circus: How to Coach Multiple Training Groups

It’s 2:50 PM on a Tuesday. The bell has rung, the locker room doors are banging open, and sixty high schoolers are spilling onto the track. You have your Varsity squad looking to qualify for States, a solid JV group that needs development, and a dozen freshmen who are still figuring out how to keep their shoes tied.

This is the reality of coaching high school distance runners. We are often managing a ‘three-ring circus” where we need to deliver high-level physiological adaptations to our elites while simultaneously teaching the basics to our novices—all within the same 90-minute window.

If you try to train everyone the same way, you fail. Your top runners will be under-stimulated, and your novices will be broken. But if you try to write sixty individual training plans, you’ll burn out by mid-season.

The solution lies in a system I call “One Bowl, Many Spoons.” Pick a workout objective (bowl) and then only give each athlete (spoons) only what they can handle.

Here is the strategy I’ve developed over the years to manage multiple training groups effectively, scientifically, and sanely.

1. The Physiological “Bowl”

The biggest mistake coaches make is thinking they need entirely different workouts for different groups. You don’t. You need different expressions of the same physiological theme.

Before I write a single rep on the whiteboard, I ask: What energy system are we targeting today?

If it’s a VO2 Max day, that’s the theme for everyone. The Varsity kids might hit that stimulus with 1000m repeats at 5k pace. The developmental group might hit it with 800m repeats. The newbies might hit it with 3-minute hard efforts.

By keeping the “Theme” consistent, you unify the team’s purpose. Everyone is doing “hard intervals” today. This allows you to address the whole team at the start of practice with one cohesive message about the goal of the workout, rather than explaining four separate agendas.

2. The Power of Duration-Based Training

If there is one tool that will save your sanity, it is the stopwatch.

When you assign distance-based reps (e.g., “Go run 4 x 1 Mile”), your group immediately fractures. Your 4:30 miler finishes in 4:45. Your 6:35 miler finishes three minutes later. By the third rep, the group is spread out over half a mile. You can’t coach them because you literally cannot see them.

Switch to time-based intervals. Instead of “4 x Mile,” assign “4 x 5 minutes at Threshold Effort.”

Now, the magic happens:

- Synchronization: Everyone starts the interval at the same time, and everyone stops at the same time. The faster kids just cover more ground. Cool. They can handle it.

- Recovery Management: You can control the rest periods perfectly. You blow the whistle to start, blow it to stop, and blow it to start again.

- Individualization: This automatically self-regulates intensity. A freshman doesn’t have to strain to hit a specific split; they just run by effort for 5 minutes.

This single shift turns a chaotic, spread-out practice into a tight, manageable unit where you can observe form, effort, and attitude for every single athlete.

3. Geographical Constraints: The “Hub” Model

Never send a large, mixed-ability group on a long “out-and-back” run if you are the only coach. You will lose the back of the pack, and that is where the injuries (and shenanigans) happen.

Design your workouts around a “Hub.”

- The Grass Loop: Find a 1000m or 1-mile loop at a local park or around your school grounds. Position yourself at the start/finish line.

- The Track (with Lanes): Use the outer lanes for recovery jogs and inner lanes for work intervals to keep traffic flowing.

When you use a Hub Model, every athlete passes you every few minutes. This allows you to give real-time feedback (“Relax your shoulders, Brody”, “Good knee drive, Alex!”) to all of your runners. It makes every athlete feel “seen”—which is crucial for team culture.

4. Categorize, Don’t Rank

We all know who the fast kids are. But for psychological safety and logistical ease, I categorize training groups by Training Age rather than just race times.

- Blue: High training age, high durability. Able to handle high volume and complex workouts.

- Red: Moderate experience. Good mechanics, but building aerobic capacity.

- White (if group is large enough): New to the sport or returning from injury. Focus is on mechanics and consistency.

I post the workout on the whiteboard in three columns. Athletes know which group they belong to. It removes the ambiguity. “Group A, you have 6 reps. Group B, you have 5. Group C, you have 4.”

Use my Run to Bike Conversion Calculator to determine what your injured athletes should be doing and for how long.

5. Standardize the Bookends

While the middle of practice (the workout) is differentiated, the beginning and end should be unified.

The Warm-up: Every athlete, regardless of ability, does the same dynamic warm-up routine together. We do our lunge matrix, our leg swings, and our drills as one massive unit. This reinforces that we are one team. It also allows captains to lead the warm-up, freeing you to set up cones or handle administrative tasks.

The Cool-down: Similarly, if feasible, bring everyone back together for the post-run core routine or stretching. This provides a clear “end” to practice and allows for team announcements.

If you fragment the warm-up, you fragment the culture.

6. Empower Your “Lieutenants”

You cannot be everywhere. Identify your veteran athletes—not necessarily the fastest ones, but the most responsible ones—and deputize them.

I assign a “Lieutenant” (or two) to the White group for easy runs. Their job isn’t to coach technique, but to manage the logistics:

- “Make sure we turn left at the fire station.”

- “Keep the pace honest—no hammering, no walking.”

- “Make sure nobody gets left behind.”

This gives your seniors ownership of the program and ensures that even when your eyes aren’t on a group, the standards of the program are being upheld.

The Bottom Line: Clarity is Kindness

Coaching multiple groups fails when the instructions are muddy. If a kid has to ask, “Wait, how many am I doing?” you have lost efficiency.

Buy a large portable whiteboard. Write the workout clearly before anyone arrives. Use color-coded markers for different groups.

When you standardize the routine, utilize time-based training, and operate from a central hub, you stop being a traffic cop and start being a coach again. You create an environment where the state champion and the kid running their first mile can both thrive, side by side.

And that, ultimately, is the job.