Speed as a Skill: A Guide for Distance Runners

The Problem with “Aerobic Base Only” Training

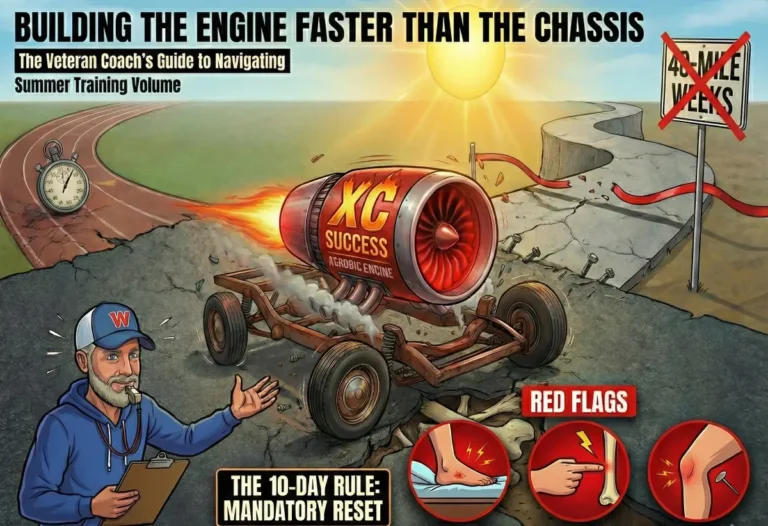

Traditional high school distance training often produces athletes who are aerobically fit but mechanically broken. By prioritizing “aerobic base” while ignoring top-end speed, coaches inadvertently lower their athletes’ performance ceiling.

The missing piece? Speed as a skill.

While most coaches focus on the metabolic system (how the body creates energy), the neuromuscular system (how the brain tells muscles to move) is actually the performance ceiling. Research by Paavolainen et al. (1999) demonstrated that explosive-strength training improved 5K times significantly—without any change in VO₂max. The athletes simply became more economical, using less energy to cover the same ground.

What is Speed Reserve in Running?

Speed Reserve is the functional gap between an athlete’s maximum sprinting velocity and their sub-maximal race pace. By increasing top-end speed, a runner reduces the relative intensity of their race pace, making it more sustainable. Let’s consider two runners trying to break 5 minutes in the mile.

| Metric | Athlete A (Fast) | Athlete B (Slow) |

|---|---|---|

| Max 400m Time | 55 seconds | 68 seconds |

| Race Pace (5:00 Mile) | 75s / lap | 75s / lap |

| % of Max Capacity | 73% | 90% |

The Takeaway: Athlete A is “cruising” while Athlete B is “redlining.” Raising the speed ceiling makes every other pace feel easier and more efficient. This is the importance of speed reserve.

Three Non-Negotiable Rules for Speed Development

Adapted from Tony Holler’s “Feed the Cats” philosophy:

- 100% Intensity – You cannot “sort of” sprint. Running at 90% trains aerobic capacity, not maximum velocity.

- Full Recovery – Neuromuscular adaptation requires a fresh nervous system. Use 1 minute of rest for every 10 meters sprinted.

- Quality over Quantity – A speed session might include only three 30-meter sprints. If athletes look tired, the session is over.

Three Essential Drills to Build the Chassis

1. Wicket Drills (The Posture Builder)

Mini 6-inch hurdles spaced 5–6 feet apart force runners into upright posture with front-side mechanics. This prevents the reaching and heel-striking that kills momentum.

The Cue: “Step over the pipe, don’t kick the bucket.”

2. Flying 30s (The Speed Ceiling)

The gold standard of speed development: 20m build-up → 30m “fly zone” at absolute max velocity → 20m deceleration.

Why it works: It trains the brain to fire muscle fibers at rates that distance running never touches.

3. Short Hill Sprints (The Hidden Weight Room)

For freshmen not ready for heavy squats, hills provide the answer. A 6–8 second sprint up a steep grade (10%+) at 100% effort forces high knee drive and glute activation.

The Benefit: It’s self-correcting. Bad mechanics are nearly impossible on a steep grade.

The High/Low Training Model

You don’t sacrifice long runs for speed—you sequence them correctly. Following Olympic sprint coach Charlie Francis’s High/Low model, group high-stress days together and follow with low-stress recovery days.

|

Day |

Intensity |

Focus |

Key Workout |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Monday |

HIGH |

Neuromuscular (Speed) |

Flying 30s & Wicket Drills |

|

Tuesday |

LOW |

Aerobic Recovery |

30-45m Easy Run + Mobility |

|

Wednesday |

HIGH |

Metabolic (Intervals) |

Critical Velocity (CV) Intervals |

|

Thursday |

LOW |

Aerobic + Drills |

30m Easy + Form Drills |

|

Friday |

HIGH |

Power (Hills) |

Short Hill Sprints (6-8s) |

|

Saturday |

MODERATE |

Long Run |

The Long Run (Conversational) |

Weekly Execution Guide

Monday: Neuromuscular Speed Day

The Workout

Warm-up: 15-minute easy jog + dynamic mobility (leg swings, gate openers)

- Wickets: 6–10 mini-hurdles (6″) spaced by height/speed. 3–4 passes.

- Flying 30s: 20m build-up → 30m fly at 100% effort → 20m deceleration. Full 3-minute rest between reps.

- Easy Finish: 3 miles at very easy, recovery pace.

Adaptations

- Freshmen: Only 2 Flying Sprints. Focus on “staying tall” through wickets. If they start reaching, stop the session.

- Varsity: 4–5 Flying Sprints. Use timing gates or stopwatch to record, rank, and publish times.

Tuesday: Recovery & Tissue Quality

The Workout

- Run: 30–40 minutes at “Conversation Pace.” If they can’t speak in full sentences, they’re running too fast.

- Mobility: 10 minutes of chassis work (Jay Johnson’s Lunge Matrix or hip/glute activation)

Adaptations

- Freshmen: 25–30 minutes. Focus on “quiet feet” to reduce shin impact.

- Varsity: 45 minutes. Add 4 light strides at the end to flush legs.

Wednesday: The “Tinman” Metabolic Engine

The Workout

- 8 × 1000m at CV pace (roughly 10K race effort) with 200m slow jog recovery (about 90 seconds)

Adaptations

- Freshmen: 4–6 × 800m instead. Goal is to finish feeling like they could do two more.

- Varsity: 8 × 1000m. Don’t “race” the workout—the last rep should match the first.

Thursday: Active Rest

The Workout

- Run: 30 minutes easy

- Form Drills: 15 minutes of intensive A-Skips, B-Skips, and Bounds. Focus on “stiff” ankle and explosive ground contact.

Friday: Structural Power (The Hill)

The Workout

Warm-up: 15-minute jog + 4 strides

- 6 × 8-second Hill Sprints on steep grade (10%+) at 100% effort

- Walk down slowly for full recovery (2–3 minutes)

- Easy Finish: 2 miles easy

Adaptations

- Freshmen: 4 reps. Coach the arm drive—”pull the grass” with your hands.

- Varsity: 8 reps. Focus on the transition from hill to flat during cool-down.

Saturday: The Long Run (Aerobic Foundation)

The Workout

- Steady, conversational effort

Adaptations

- Freshmen: 45–50 minutes (time-based only—don’t worry about mileage)

- Varsity: 75–90 minutes. Can include a “fast finish” (last 10 minutes at slightly picked-up pace) if feeling fresh.

The Bottom Line

Training only the engine while neglecting the chassis creates runners who break down. By treating speed as a skill, practiced with intention and proper recovery, you build athletes who are both aerobically fit and mechanically sound.