Swimmer to Track Runner Transition: Your 6-Week Senior Season Protocol

That chlorine sting? Feels like a warm hug. The flip-turn rhythm? It’s wired into your DNA now. Your aerobic engine? It’s never been more dialed in.

But for a senior distance runner like Kaitlin, jumping from the pool to the outdoor track is like driving a Ferrari engine on a go-kart chassis. One sharp turn, and the whole thing falls apart. Kaitlin is a standout swimmer and a cross country varsity captain, but she remembers the “sledgehammer” pains of seasons past. Those weren’t just aches—they were the warning signs of a structural collapse.

She wants to go out with a PR, not a walking boot. She needs a bridge—one that keeps that massive aerobic fitness intact while turning her body into something that can handle the relentless pounding of the track without shattering. The research is crystal clear on this—the bone stress injury prevention research from AMSSM has documented repeatedly that bone stress injuries in high school athletes spike when impact loading increases too rapidly.

We’re not just looking for ‘swimmer-fit’—we’re looking for ‘track-sturdy.’ The secret to this season isn’t more volume; it’s a surgical approach to leaving the weightless sanctuary of the pool. You’ve seen a sea turtle emerge from the waves—an elite navigator of the deep that suddenly looks clumsy and strained the moment it touches the dunes. That is the water-to-land struggle in a nutshell. You have the engine to fly, but first, we have to teach your bones how to walk on land.

Why Swimmers Struggle With Running

Here’s what nobody tells you about making the jump from water to land: swimming and running are biomechanical opposites, and your body knows it.

In the pool, you’re horizontal. Gravity is neutralized. Every stroke happens in a fluid environment that supports your body weight and cushions every movement. Your hip flexors are in a shortened position for thousands of meters. Your feet? They’re pointed, not flexed. Your core is extended, not compressed. You’ve built an aerobic monster, but you’ve done it in zero-impact conditions.

Now you’re vertical. Gravity is no longer your friend—it’s applying 2-3x your body weight with every foot strike. Your hip flexors, adapted to that streamlined swimming position, are now screaming as they try to achieve the hip extension running demands. Your feet, which haven’t had to absorb shock in months, are getting pounded into the ground 160-180 times per minute. Your bones haven’t experienced loading forces in so long that they’re structurally unprepared for the stress.

This isn’t a fitness problem! You are super fit if you’ve been training and racing in the pool! This is a structural adaptation problem. The research backs this up: swimmers transitioning to running show significantly lower bone mineral density in weight-bearing bones compared to year-round runners. You’ve got the engine. You just need the chassis to handle it.

The 6-Week Structural Bridge Protocol for Multi-Sport Athletes

This isn’t some Couch to 5K program. This is a precision-engineered plan to take you from the pool to the track without breaking down. The framework follows the same science-backed periodization principles you’ll find in the from USATF—the gold standard for building athletes who last.

Phase I: Impact Re-Acclimation

Weeks 1-2The Goal: Turn fragile shins into iron by re-introducing impact on forgiving, natural surfaces and treadmills.

We’re going “Soft-First.” Grass fields, dirt paths, gravel rail trails—anything natural. Avoid cold, sterile indoor tracks or asphalt until your bones and tendons remember what impact feels like.

The “Quiet Feet” ProtocolHigh cadence (170-180 SPM) and mid-foot strike. If you’re pounding the ground like you’re trying to crack the earth open, you’re doing it wrong. Avoid long, thumpy strides.

The Volume SplitRun 3–4 days/week (30-35 mins) at a Zone 2, “Easy” effort. Continue pool work to protect your aerobic capacity while your skeletal system catches up.

Phase II: Structural Integration

Weeks 3-4The Goal: Build genuine strength and find your rhythmic flow without becoming a slave to the stopwatch.

Surface SelectionThe shift begins: 80% natural surfaces (trails/grass), 20% road/track. Earn your way back to the hard stuff.

The Unstructured TempoLeave the GPS watch at home. Run “to the horizon” on a trail (35-40 minutes, 4 days/week) at easy to medium effort. No splits. Just you and your breathing.

The Mental EdgeBreak free from the mathematics of the 200-meter oval. Restore your internal metronome and find your flow state based on feel, not lap counting.

Phase III: Speed & Track Sharpening

Weeks 5-6The Goal: Safely sharpen speed for when the starter’s pistol fires.

The 50/50 SplitEqual balance—50% natural surfaces, 50% track work. You’ve earned this.

Variable Strides6–8 x 100m strides on packed dirt or gravel. The instability forces aggressive glute engagement and a more powerful toe-off than a predictable track surface.

Track IntegrationOne interval session per week on the track (e.g., 400m repeats with “teeth”). Everything else stays on softer terrain to avoid repetitive stress from track turns.

Sample Weekly Routine

| Day | Training Session |

|---|---|

| Monday | 45 minutes Easy + 4x Strides |

| Tuesday | 10m WU, 6×400 (3200m Race Pace, 90s Rest), 10m CD + Weights |

| Wednesday | 30 minutes Easy + 4x Strides |

| Thursday | Rest Day |

| Friday | 35 minutes Easy + 4x Strides + Weights |

| Saturday | 50 minutes Easy |

| Sunday | Rest Day |

Foundation & Steel: Injury Prevention Routine for Runners

Twice weekly. Twenty minutes. Non-negotiable.

1. Single-Leg “Clock” Hops

Repetitions: 5x Per Leg The Action: Balance on one leg. Perform small, controlled hops to the 12, 3, 6, and 9 o’clock positions.

Coach’s Note: This builds ankle resilience—the literal foundation of your stride. If your ankles can’t handle it, your speed doesn’t matter.

2. Bent-Knee Calf Raises

Repetitions: 10x Per Leg The Action: Perform a calf raise with a slight bend in the knee.

Coach’s Note: This targets the soleus muscle, which absorbs 6–8x your body weight every single stride. This is your #1 defense against shin splints.

3. Eccentric Step-Downs

Repetitions: 5x Per Leg The Action: Stand on a curb or step. Slowly lower one foot (heel first) with a 3-second descent.

Coach’s Note: You are training the “braking” mechanism of the lower body. This protects your knees from the impact forces that destroy unprepared runners transitioning from the pool.

4. Natural Surface Lunges

Repetitions: 10x Alternating The Action: Slow, deliberate lunges performed on uneven ground (grass, gravel, or dirt).

Coach’s Note: This is functional strength. By avoiding flat, synthetic surfaces, you force your stabilizers to fire harder. This keeps your form intact when fatigue sets in at the end of a 3200m race.

Athlete Implementation:

- Frequency: 2–3 times per week.

- Timing: Immediately following your runs.

- Quality over quantity: If you can’t control the landing, slow down.

5 Common Mistakes to Avoid

Swimmers make the same five mistakes when transitioning to track. Here’s how to avoid them:

Mistake #1: “I’m Already Fit, So I Can Skip the Easy Stuff” Your cardiovascular system is fit. Your bones and tendons are not. Fitness and durability are not the same thing. Trying to run the volume your aerobic capacity can handle before your skeletal system is ready is how you end up in a walking boot.

Mistake #2: Jumping Straight to Track Intervals Swimming made you aerobically ready for speed work, but it didn’t prepare your body for the repetitive impact loading of 400m repeats on synthetic surface. Earn the track through progressive adaptation first.

Mistake #3: Ignoring the Strength Work You think you don’t need single-leg exercises because you feel strong. However, your core, glutes, and soleus aren’t prepared for the eccentric loading demands of running. Do not skip the Foundation & Steel exercises.

Mistake #4: Abandoning the Pool Completely You don’t have to choose. Keep 1-2 swim sessions per week during the early transition. It maintains your aerobic ceiling while your running legs catch up. The pool is recovery and capacity maintenance—use it strategically.

Mistake #5: Comparing Yourself to Year-Round Runners They’ve been absorbing impact all winter. You haven’t. Their bodies are adapted. Yours isn’t—yet. Don’t let ego drive your training decisions in January. Be patient now, be dangerous later 😈.

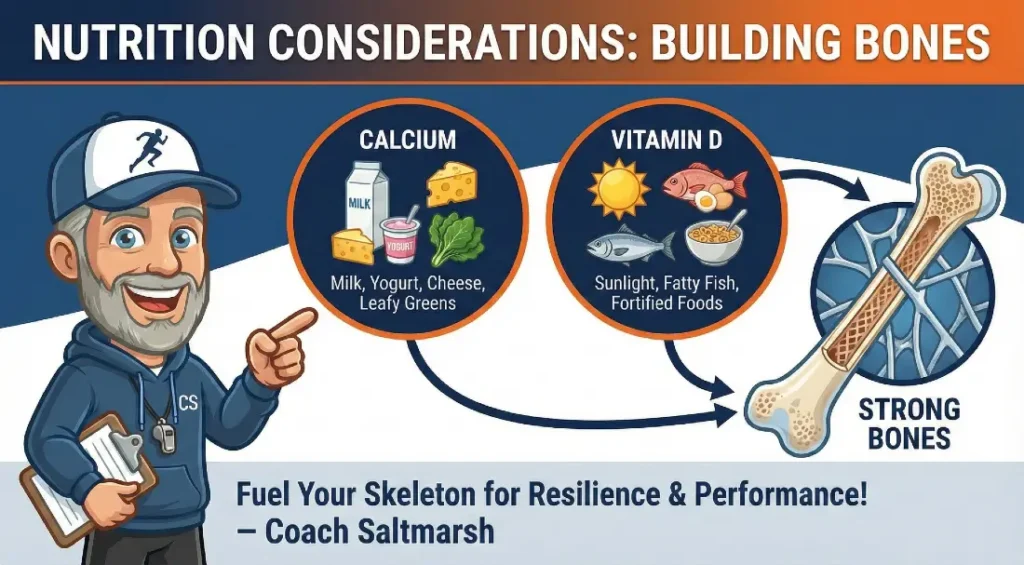

Nutrition Considerations: Building Bones

Impact loading creates entirely different demands on your skeletal system, and if you’re not fueling for bone adaptation, you’re setting yourself up for a stress fracture.

Calcium is non-negotiable. You need 1,300mg daily minimum—that’s about four servings of dairy or fortified alternatives. Your bones are literally remodeling themselves to handle impact forces they haven’t experienced in months. Give them the raw materials they need. Greek yogurt, milk, fortified orange juice, leafy greens—make them staples, not afterthoughts.

Vitamin D is your calcium’s partner. You can’t absorb calcium efficiently without adequate vitamin D. Target 600-800 IU daily, and if you’re training indoors all winter in New Hampshire (I see you Kaitlin), you’re probably deficient.

Protein timing matters more now. You’re not just maintaining muscle—you’re building structural resilience. Aim for 0.7-0.8g per pound of body weight, distributed across the day. Post-run protein isn’t just for recovery; it’s for adaptation.

Don’t gamble with your skeleton. Fuel it properly, or pay the price in lost training weeks.

Frequently Asked Questions

Six weeks minimum for structural adaptation, but that doesn’t mean you’re ready to race. Your bones need 6-8 weeks to increase mineral density in response to impact loading—that’s not negotiable biology. The Structural Bridge Protocol gets you to the starting line safely. Racing fitness comes after you’ve built durability. Don’t rush it.

Keep 1-2 swim sessions per week during the transition phase (Weeks 1-4) for active recovery and cardiovascular maintenance. The pool built your engine—don’t abandon it completely.

Simple: impact loading shock combined with structural unpreparedness. Your tibialis anterior and soleus muscles haven’t had to eccentrically control foot strike forces for months. Your bones haven’t experienced repetitive loading. When you suddenly ask them to absorb 2-3x your body weight 180 times per minute, they rebel. The bent-knee calf raises and soft-surface progression in the protocol directly address this.

You can if you have to, but you’re missing the point. The treadmill is still a repetitive, predictable surface that doesn’t force your stabilizer muscles to work. Trail and grass running create subtle variations in foot strike that build resilient ankles and more robust movement patterns. The treadmill is better than asphalt, but it’s not better than dirt. Use it for weather emergencies, not as your default.

It depends. If you took December-January off from running to focus on swimming, then yes—you’ve deconditioned your running-specific structures and need to rebuild them. If you’ve been maintaining 2-3 runs per week through swim season, you can abbreviate the protocol to 3-4 weeks. But if you completely stopped running for 8+ weeks, your body needs the full reacclimation period. Don’t let your cross country fitness from October fool you—it’s January now.

Stop. Immediately. Shin pain during the transition is your body screaming that you’re progressing too fast. Drop back to pool running and swimming-only for 3-5 days. When you return to running, reduce volume by 30-40% and ensure you’re on the softest surfaces possible. Add an extra day of the Foundation & Steel routine, especially the bent-knee calf raises. If pain persists beyond one week or occurs at rest, see a sports medicine physician—stress reactions don’t heal with wishful thinking.

Three checkpoints: (1) You’re completing all prescribed runs without pain during or after, (2) You’re not excessively sore 24-48 hours post-run, and (3) You’re sleeping well and feeling recovered between sessions. If you’re checking all three boxes consistently within a phase, you’re ready to progress. If you’re struggling, extend that phase by another week. This isn’t a race—it’s a construction project.