Mastering 5K Race Strategy: A Science-Backed Guide for Coaches

I stood at the one-mile mark of a divisional championship 5K watching one of my best runners—someone who had trained flawlessly for twelve weeks—blow up spectacularly. She’d gone out in 5:45 for the first mile when her fitness supported 6:05. By two miles, she was shuffling and having difficulty just keeping her chin up and eyes forward. By 2.5 miles, her race was in slow motion decline and she was suffering. Our 2nd runner became our 7th that day, and to the disappointment of the team, we missed going to States by single digits.

After twenty years of coaching distance runners, I’ve learned that talent and training get you to the starting line. Race strategy gets you to the podium. The athletes who consistently perform at championships aren’t always the most gifted; they’re the ones who’ve learned to race strategically.

Arthur Lydiard, the legendary New Zealand coach who guided Peter Snell and Murray Halberg to Olympic gold, said it best: “You must condition the body first so that it can stand the hard fast work.” But once conditioned, athletes must learn to deploy that fitness tactically. Steve Magness, who coached at the University of Houston and trains professional runners, emphasizes that “losing focus is a real limiting factor when it comes to peak performance.” His training introduces uncertainty—no watches, misplaced distance markers, unpredictable group dynamics—to prepare athletes for the chaos of actual competition.

This isn’t just theory. These are principles that separate athletes who run well in practice from those who execute when it matters. In this article, I’ll share with you the race strategies that work—backed by research, validated by elite coaches, and proven by champions.

The Science of Pacing: Why Even Splits Are a Myth (Sort Of)

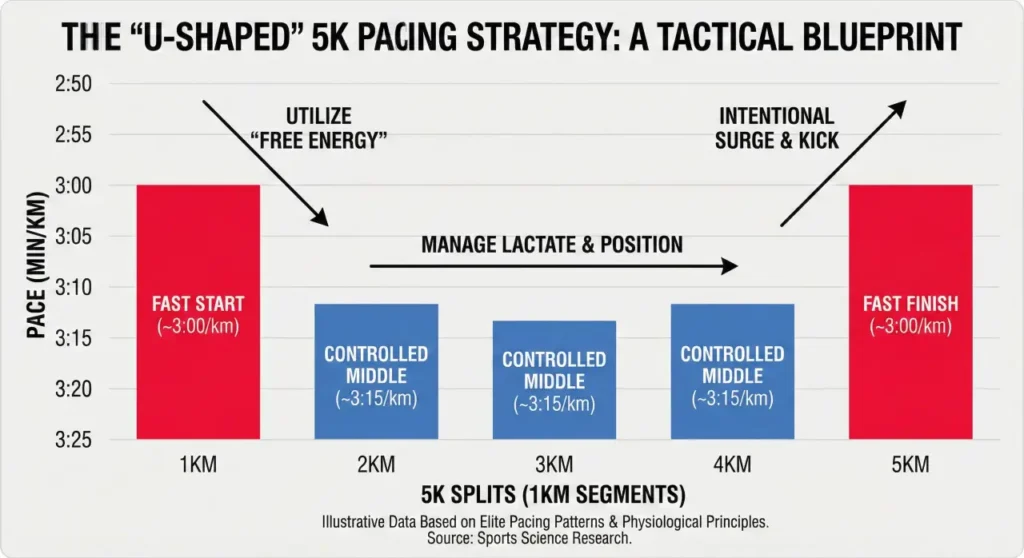

For decades, coaches preached even-pace running as gospel. Run every mile at the same speed, we said, because it’s the most physiologically efficient distribution of effort. Then Alex Hutchinson, author of Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance, analyzed every 5,000m and 10,000m world record set in the modern era.The data was unambiguous: the first kilometer and the last kilometer were faster than every other kilometer in the race. Every. Single. Record.

Why? Hutchinson explains that “you have a little bit of free energy, a little bit of energy that you can use up without particular cost in the first couple of minutes of a race.” Your phosphocreatine (PCr) system—the immediate energy source for explosive efforts—provides a boost at the start. If you don’t use it early, you waste it.

But here’s the critical nuance: this doesn’t mean you should sprint. The research from COROS sports scientists confirms that elite 5K pacing follows a specific pattern: slightly fast first kilometer, controlled middle kilometers where lactate is managed, and a progressively faster final kilometer where athletes allow lactate accumulation because the finish line is near.

The takeaway for high school coaches? Teach your athletes to run the first 800m of a 5K about 3-5 seconds faster per mile than goal pace, settle into rhythm for the middle 2 miles, and then progressively accelerate from 2.5 miles to the finish. This isn’t reckless; it’s strategic use of available energy systems.

The Four Phases of a Strategic 5K Race

Joe Vigil, the legendary coach who guided Deena Kastor and the Adams State distance dynasty, emphasized understanding the physiological demands of each race phase. Here’s how to break down a 5K:

Phase 1: The Opening 800m (Positioning Without Panic)

The Goal: Establish position without depleting glycogen stores.

In a competitive field, the first 400m determines whether you’re running in traffic or running in space. Cross country courses with narrow trails or funnel points make this even more critical. Steve Magness teaches his athletes to “get comfortable with uncertainty”—you can’t control the start, but you can control your response.

Tactical Principles:

- Run 3-5 seconds per mile faster than goal pace, no more

- Focus on external positioning (stay out of boxes, avoid the inside of turns where congestion forms)

- Relax your shoulders, keep your breathing controlled

- If the pace feels “comfortably hard,” you’re right. If it feels “hard,” you’ve gone out too fast

Phase 2: Miles 1-2 (The Patience Test)

The Goal: Maintain contact with your competitors while running at or slightly below threshold pace.

This is where races are lost. Athletes who went out too fast begin to fade. Your job is to run your race while staying tactically positioned. As Hutchinson discovered in his research, elite runners intentionally slow during the middle kilometers—not because they’re tired, but because they’re rationing energy for the finish.

Lydiard‘s athletes were taught to run “best maximum steady-state pace” during aerobic conditioning, developing the neuromuscular efficiency to hold a challenging-but-sustainable effort. This phase of the race tests whether your training properly developed that capacity.

Tactical Principles:

- Stay within 3-5 seconds of the leaders (close enough to respond, far enough to avoid their mistakes)

- On cross country courses, position yourself on the outside of turns to maintain momentum

- Use downhills to recover slightly; maintain effort (not pace) on uphills

- Focus on rhythm and relaxation—if your jaw is clenched, you’re wasting energy

Phase 3: Miles 2-2.5 (The Mental Crucible)

The Goal: Resist the urge to slow down when discomfort peaks.

Between 2 miles and 2.5 miles in a 5K, lactate accumulation accelerates, perceived exertion spikes, and your brain begins sending urgent messages to slow down. Alex Hutchinson’s research on the “Central Governor Theory” suggests that these signals aren’t just physiological—they’re protective mechanisms your brain uses to prevent catastrophic failure.

Elite athletes have learned to reinterpret these signals. As Hutchinson notes, “If you’re a beginner, regardless of how fast you are, you probably haven’t learned to hold your finger in the flame quite as long.” Championship-level athletes don’t experience less discomfort; they’ve simply trained themselves to tolerate higher levels of it.

Tactical Principles:

- Expect discomfort and reframe it: “This means I’m running hard”

- Make your move or respond to moves during this phase—waiting until the final 400m is often too late in high school competition

- On hilly cross country courses, attack over the top of hills (when opponents are recovering)

- Break the race into micro-goals: “Get to that tree,” then “Get to that cone”

Weather Considerations

Hot/Humid Conditions: Your pace will be 15-30 seconds per mile slower than cool conditions. The Central Governor protects against heat stroke by forcing you to slow down. Don’t fight it in miles 1-2; accept the slower pace and rely on superior mental toughness in miles 2-3.

Cold/Windy Conditions: Use competitors as windbreaks during miles 1-2. Make your move when you turn with the wind, not into it. Cold weather favors athletes with superior cardiovascular fitness over those relying on speed.

Muddy/Technical Courses: Slow down less than your competitors on difficult terrain. While they’re tip-toeing through mud, maintain effort and pass them. Technical courses reward courage and bike-handling skills from cross-training.

Phase 4: The Final 800m (Controlled Aggression)

The Goal: Run the last half-mile faster than any other segment while maintaining form.

COROS sports scientists explain that during the final 1000m, “you can let loose and allow lactate and hydrogen ions to accumulate faster than your body can clear them.” You’ve spent 2.1 miles managing lactate; now you’re going to produce it intentionally.

Steve Magness’s research confirms that the ability to finish strong isn’t just about fitness—it’s about having trained your neuromuscular system to recruit muscle fibers efficiently when fatigued. This is why he emphasizes sprint drills and form work throughout the training cycle.

Tactical Principles:

- Accelerate gradually from 2.5 miles to 3 miles, don’t wait for a “kick”

- Focus on form: drive your knees, pump your arms, lift your chest

- In the final 400m, commit fully—there’s no saving energy for later

- If you still have PCr stores (explosive energy), use them in the final 200m

Calculates optimal 800m splits for your runners based on goal time for each of the 4 phases.

Cross Country Tactics: Hills, Mud, and Grass

Cross country isn’t run on flat, predictable tracks. Your athletes need sport-specific strategies.

Uphill Running Strategy

The Conventional Wisdom: Attack the hills, pass people going up.

The Smart Approach: Maintain your effort (not pace) going up, then accelerate over the crest and down the other side.

Physiologically, pushing hard uphill depletes glycogen stores disproportionately. Athletes who surge up hills often fade immediately after cresting. Instead, teach your runners to:

- Shorten their stride and increase cadence on uphills

- Lean slightly forward from the ankles

- Maintain effort while accepting a slower pace

- Explode over the top of the hill when competitors are recovering

- Carry momentum down the other side

The athletes who gain the most time on hills aren’t the ones who charge up them—they’re the ones who recover less at the top.

Downhill Running Strategy

Downhills should be free speed, but most high school runners brake excessively because they’re afraid of losing control. Teach them to:

- Lean slightly forward (not back)

- Increase cadence, not stride length

- Stay light on their feet—imagine running on hot coals

- Let elbows/arms move out to the side for balance

- Don’t land on your heels

- Use gravity to build momentum for the next uphill

Elite athletes gain 5-10 seconds on competitors during downhill sections simply by being less cautious.

Running in Mud, Sand, or Soft Terrain

When the course deteriorates, strategy matters more than fitness. The athlete who slows down the least on bad terrain wins.

Key Principles:

- Shorten your stride—trying to maintain stride length in mud wastes energy

- Pick up your knees—minimize ground contact time

- Accept that everyone slows down; focus on slowing down less

- Look ahead 10-15 meters to identify the best footing

A 16:30 5K runner who handles mud well will beat a 16:00 runner who doesn’t. This is where cross country rewards toughness over pure speed.

The Mental Game: What Separates Good From Great

Elite athletes don’t experience less pain than high school runners. They’ve simply learned to expect it, accept it, and push through it.

Bernard Lagat, four-time Olympian and one of the greatest middle-distance runners in U.S. history, claims his success came from his ability to race tactically in finals where fitness is equal and strategy determines outcomes.

Teaching Mental Resilience

During Training:

- Run time trials without watches so athletes learn to run by feel

- Practice “surge and recover” workouts where athletes respond to random accelerations

- Include race-simulation workouts with competitive scenarios

During Racing:

- Teach athletes to count breathing patterns (e.g., “3 steps inhale, 2 steps exhale”) during discomfort—this provides a cognitive anchor

- Use external cues: “Focus on the spot between the runner’s shoulder blades in front of me” rather than internal cues like “my legs hurt”

- Break the race into segments: “I just need to stay strong until the next turn”

Coaching Game Plan: The Pre-Race Strategy Session

Two days before a championship race, hold a 15-minute team meeting covering:

Course Reconnaissance:

- Walk the course if possible; if not, study video or satellite imagery

- Identify the first turn (where positioning matters most)

- Locate all significant hills (where to maintain vs. where to attack)

- Note the final 400m layout (straight? Turn? Uphill finish?)

Individual Pacing Plans:

- Based on current fitness, assign each athlete a target 800m split for Phase 1

- Emphasize that going out 5 seconds too fast is worse than 5 seconds too slow

- Remind them: “You can’t win in the first mile, but you can lose it there”

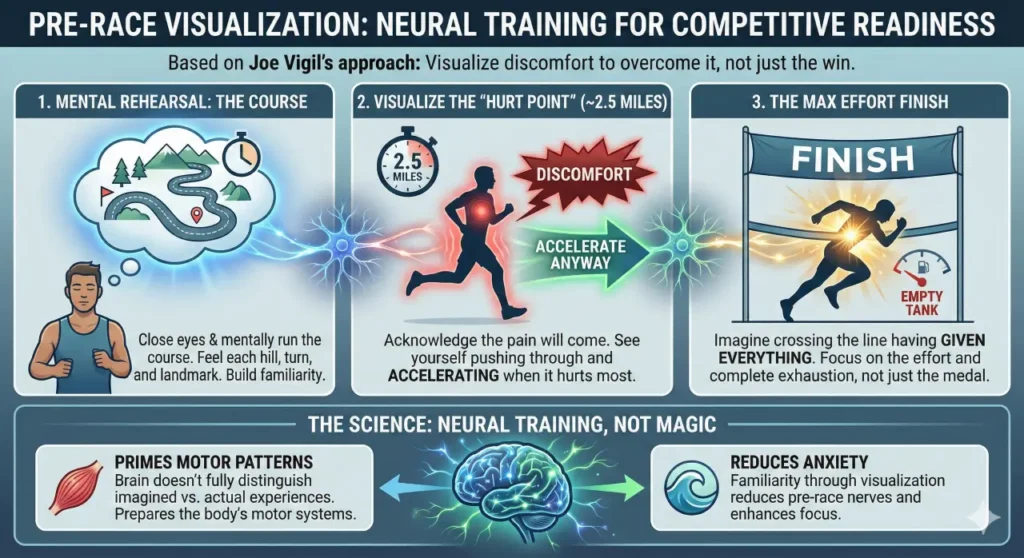

Mental Preparation:

- Normalize discomfort: “Everyone at 2.5 miles will hurt. The winner is whoever hurts and keeps pushing. No quit, no mercy!”

- Establish a mantra: “Strong and smooth”

- Review visualization protocol

Team Tactics:

- If scoring matters, discuss pack running: “If you’re in 8th place and a teammate is in 9th, slow down and let them pass you if they’re stronger”

- Identify competitors: “Stay with the green singlet through 2 miles, then drop them”

What Coaches Get Wrong About Race Strategy

Mistake #1: Treating All Athletes the Same A front-runner with a strong aerobic base should race differently than a kicker with superior speed.

Mistake #2: Ignoring the Competition Your athlete might be fit enough to run 16:30, but if the lead pack goes out in 5:50, they need to make a decision: go with them and risk blowing up, or run their pace and hope to catch them later. There’s no universal answer—it depends on the athlete’s strengths.

Mistake #3: Valuing the Kick Too Highly High school races are won in miles 2-3, not in the final 200m.

The Long-Term View: Strategy Development Across Seasons

Arthur Lydiard taught that talent is universal—it’s training that unlocks potential. The same applies to race strategy. Athletes aren’t born with tactical awareness; they develop it through:

Freshman/Sophomore Years:

- Focus on learning proper pacing

- Emphasize effort-based racing over time-based racing

- Run shorter time trials (1600-3000m) to practice phase management

Junior/Senior Years:

- Introduce tactical scenarios in workouts: “Respond to a surge at 2 miles”

- Study race video together, analyzing where races were won/lost

- Give athletes autonomy: “You know the plan. Trust yourself to execute it.”

Joe Vigil’s legacy at Adams State proves this approach works. He didn’t recruit five-star athletes—he developed ordinary runners into national champions by teaching them to think tactically and execute relentlessly.

The Final Word: Controlled Aggression

The best race strategy isn’t conservative. It isn’t reckless. It’s controlled aggression—running at the edge of your ability while making smart decisions about when to push and when to recover.

Alex Hutchinson’s research shows that “the limits of human endurance are curiously elastic”—they bend when athletes learn to push through discomfort. And Lydiard proved that ordinary athletes, properly trained and tactically prepared, can beat more talented competitors who don’t know how to race.

Your job as a coach isn’t to make your athletes faster on race day—the training already did that. Your job is to teach them to deploy their fitness intelligently, to make split-second tactical decisions under fatigue, and to push through discomfort when their brain is screaming to slow down.

Because at the end of the day, the athlete standing on the podium isn’t always the fastest runner in the field. They’re the best one that day.

Related Resources:

→ Complete Guide to Coaching High School Distance Runners

→ Building a Culture of Excellence in High School Running

→ The 3 Essential Workouts Every XC Runner Needs