Developing Young Distance Runners: Talent, Patience, and Burnout

An eighth-grader showed up to my first practice wearing basketball shorts and generic running shoes from Kohl’s. He’d never run competitively. Didn’t know what a PR was. Couldn’t tell you the difference between a 400 and an 800. But when we did our baseline mile time trial, he ran 5:47 like it was a Sunday jog, chatting with his buddies the entire way.

That kid went on to run sub-10:00 for the 3200m as a senior and got multiple offers to run in college. But here’s what I learned: for every obvious talent like him, I’ve coached three kids who looked ordinary at thirteen and became champions by eighteen—and I’ve coached just as many “can’t-miss” prospects who quit before junior year.

After two decades of coaching distance runners and working with dozens of state champions, I’ve come to understand something fundamental: identifying talent in young runners isn’t about finding the next Footlocker champion in seventh grade. It’s about recognizing potential, protecting it from premature specialization, and creating an environment where talent has permission to develop slowly.

Because here’s the truth every high school coach needs to hear: most of the kids standing on state championship podiums weren’t the best runners in middle school. They were just the ones who stayed healthy, stayed interested, and had coaches who understood the difference between training a twelve-year-old and training a seventeen-year-old.

What Actually Predicts Future Success in Youth Running (It’s Not Times)

Steve Magness ran 4:01 for the 1600m in high school—one of the fastest times in the nation. He went on to become one of the world’s leading running coaches and authors of The Science of Running, working with Olympians and World Championship medalists. When asked about identifying talent in young runners, his answer might surprise you.

“Youth coaches are the most important,” Magness emphasizes. “They set up the patterns for which their athletes will view the sport for the rest of their life… At the college and even professional level, you can trace the mindsets of the runners back to their early competitive days.”

He didn’t mention VO2max testing. He didn’t talk about lactate threshold. He talked about mindset. Because the research consistently shows that psychological characteristics—motivation, resilience, coachability—are better predictors of long-term success than early physical performance.

Renato Canova, the legendary Italian coach who’s guided over 50 Olympic and World Championship medalists, explains that athletes need “8-10 years for building their aerobic house.” He notes that many of his elite African runners had years of natural, unstructured activity as children—”running at different speeds, building aerobic efficiency when still very young.” This wasn’t formal training; it was play. And that distinction matters enormously.

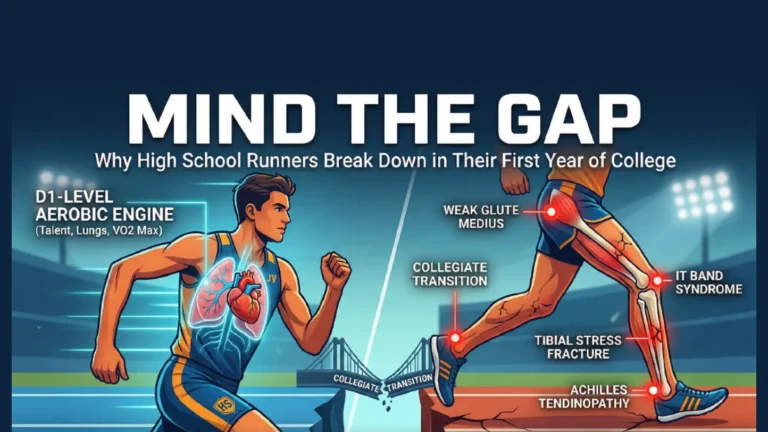

Greg McMillan, who coaches everyone from beginners to Olympians, describes what he calls “The Discovery”—the athlete who shows up with zero running experience but natural talent emerges almost immediately. “He was usually a freshman or sophomore with little running experience, but boy, could he run,” McMillan writes. “With Discoveries, the coach has a careful balancing act… injuries are common with talented athletes with few miles under their belts.”

So what should you look for when a middle schooler or freshman shows up at practice?

The 5 Indicators of Running Talent in Middle School

1. Movement Efficiency Over Raw Speed

Scott Christensen, whose teams have been ranked in the national top 10 eight times, emphasizes watching how kids run, not just how fast. Look for natural rhythm, relaxed shoulders, and minimal wasted motion. The kid who runs 6:15 for the mile with smooth mechanics will likely improve more than the kid who runs 5:55 by grinding and forcing every step.

2. Competitive Drive Without External Pressure

Does the kid want to win because they want to win, or because their parents want them to win? Steve Magness calls this distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. “If they had a hard nosed coach they were afraid of, 10 years down the line, the athlete still displays a fear of failure when racing.”

Arthur Lydiard, whose New Zealand coaching system produced multiple Olympic champions like Peter Snell, believed deeply in athlete autonomy. His runners trained hard because they chose to. That internal drive is what sustains athletes through thousands of rigorous training miles.

Watch how young runners respond when they don’t perform well. Do they immediately look at their parents? Do they make excuses? Or do they ask thoughtful questions about what went wrong? The latter group has talent you can develop.

3. Coachability and Growth Mindset

Research from the Journal of Athletic Training on talent identification in young athletes consistently shows that coachability—the willingness to receive feedback and adjust—predicts long-term success better than early performance metrics.

The best runners that I have had the privilege to coach all listened intently to every coaching cue, asked questions about form, and implemented feedback immediately. Many of them were running sub-4:30 (boys) or sub-5:00 (girls) in the 1600m by senior year with low mileage levels that most coaches would laugh at.

Talent without coachability is like horsepower without steering.

4. Relative Aerobic Capacity

Here’s where we get slightly technical, but it matters. Young talented distance runners often show VO2max values above 60 ml/kg/min for boys and 55 ml/kg/min for girls, even before structured training. But here’s the thing: HS coaches don’t have access to a sports science lab to measure this.

Instead, look for kids who recover quickly between efforts. During a practice where you’re doing 400m repeats, the talented kid isn’t just running fast—they’re bouncing back to normal breathing within 90 seconds. Their heart rate drops rapidly. They’re ready to go again while others are still bent over.

This recovery capacity is trainable, but kids with naturally efficient cardiovascular systems show it early. It’s visible in the beep test, in time trials, in any scenario where you stress the aerobic system and then watch what happens during recovery. Observation is 90% of coaching.

5. Multi-Sport Background

This one surprises coaches who think early specialization is necessary. Steve Magness is unequivocal: “You do NOT need to specialize in order to reach your potential. In fact, specializing early is more likely to ensure that you never get the most out of your talent.”

Research on sport specialization in adolescent runners shows that highly specialized middle schoolers report higher running volume and more competition months per year—but no differences in injury rates or long-term success compared to multi-sport athletes. The specialized kids often plateau earlier or burn out.

The best mid-distance runner I ever coached played soccer in fall and ran track in spring. He played baseball freshman year. He didn’t “focus on running” until junior year. By senior year, he was a state champion and had the fastest times in the 800m (1:53) and 1600m (4:18) in school history. His multi-sport background gave him coordination, power, and—crucially—protection from overuse injuries that sideline single-sport specialists.

Managing Parents and Protecting Talent from Premature Expectations

Here’s where most coaches fail. They identify a talented seventh or eighth grader, get excited, and either push too hard or let the parents’ expectations dictate the training. Both paths lead to burnout.

When a middle schooler with obvious talent joins your program, schedule a meeting with the parents before the first workout. Here’s the sample script:

“Your child has real talent. I can see it in their movement, their recovery capacity, and their competitive drive. But here’s what I need you to understand: the goal isn’t to make them the best 14-year-old in the state. The goal is to make them the best 17 or 18-year-old they can become. That requires patience.”

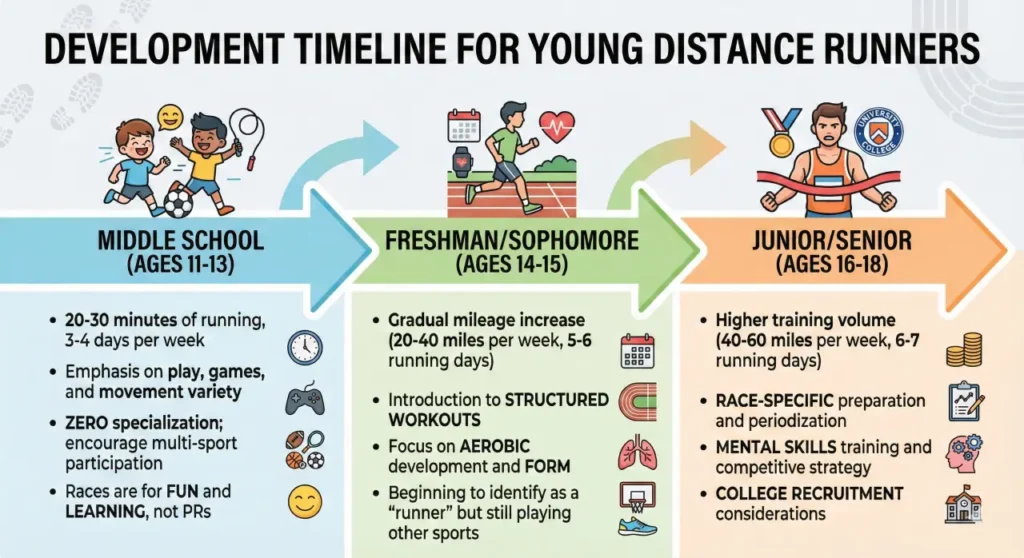

Then outline the development timeline:

📈 Long-Term Development Framework

Ages 11-13 Middle School

- 20-30 minutes of running, 3-4 days per week

- Emphasis on play, games, and movement variety

- Zero specialization; encourage multi-sport participation

- Races are for fun and learning, not PRs

Ages 14-15 Freshman / Sophomore

- Gradual mileage increase (20-40 miles per week, 5-6 running days)

- Introduction to structured workouts

- Focus on aerobic development and form

- Beginning to identify as a “runner” but still playing other sports

Ages 16-18 Junior / Senior

- Higher training volume (40-60 miles per week, 6-7 running days)

- Race-specific preparation and periodization

- Mental skills training and competitive strategy

- College recruitment considerations

Share your philosophy and help parents’ understand your approach to longterm development. It will make your life as a coach easier and help you avoid headaches down the road.

Keeping it Fun: Preventing Running Burnout with Games

For middle schoolers, fun isn’t optional. It’s structural. Scott Christensen recommends “running-type games” that develop fitness without feeling like workouts:

The Potato Chip Run

Before a distance run, give each runner an unbroken Pringle chip. They palm it and run 2 miles. The goal? Return with the chip intact. This teaches upper body relaxation and focus while making the run feel like a challenge rather than drudgery. For my high school runners, I have them do the same thing but for 5x 100m strides.

Recruiting Strategy: Attracting Middle School Talent

Middle school coaches often ask: “Should I actively recruit talented kids from gym class or other sports?” The answer is yes—but carefully.

Here’s what works:

1. Build a Culture They Want to Join

If your high school program has a reputation for being positive, successful, and fun, you don’t need to recruit. Talented middle schoolers will show up voluntarily because their older siblings or neighbors talk about how great the team is.

2. Host a “Step-Up or Try Running” Day

Invite all 7th and 8th graders to a low-pressure Saturday morning where they run games, do relay races, and meet high school runners. No pressure, no clipboard with times, no cuts. Just exposure and relationship building.

3. Leverage Your Current Athletes

Upperclassmen are the best recruiters. When your state champion talks to an eighth-grader about how fun the team is, that carries more weight than anything you could say. Create a mentorship program (ex: Big Sisters) where incoming freshmen are paired with juniors/seniors.

5 Coaching Mistakes That Derail Long-Term Athlete Development

Mistake 1: Training Them Like Small Adults

Middle schoolers aren’t miniature high schoolers. Their growth plates aren’t fully formed until age 14-16. Their aerobic systems respond differently to training stimuli. Their hormonal profiles are completely different. Research on youth running consistently shows that training loads appropriate for 17-year-olds cause injury and burnout in 13-year-olds.

Mistake 2: Letting Parents Dictate Training

The parent of a talented middle schooler will google “elite running training” and find programs designed for 22-year-old professionals running 120 miles per week. Then they’ll email you asking why their son is only running 25. To make matters worse, they often spend money on ‘club’ coaches who make promises based on shortsighted training approaches.

Your job is to educate, not accommodate. Show them the data on overuse syndrome, and early specialization burnout. Steve Magness emphasizes that “kids whose parents are pushing them to train 20 hours a week eventually flame out because they specialized too early.” Stand firm.

Mistake 3: Comparing Them to Other Young Athletes

The 7th grader running 5:20 for the mile isn’t “behind” the 7th grader running 5:00. They’re on different developmental timelines. Boys often don’t hit peak height velocity until age 14-15. Be patient, be flexible and be positive. Judge athletes against their own baseline, not against their peers.

Mistake 4: Racing Too Frequently

Research shows that young runners benefit more from consistent training interrupted by occasional competitions than from constant racing with minimal training between events. Lydiard’s philosophy—build the aerobic base first, add speed later—applies especially to young runners.

Mistake 5: Ignoring Non-Running Development

Talented young runners need strength training, mobility work, and technical drills—not just more miles. Joe Vigil’s athletes at Adams State did extensive post-run routines focused on injury prevention and movement quality.

Scott Christensen recommends plyometrics 2-3 times per week for middle schoolers: “bounding, skipping, high knees,” not high-impact box jumps. These develop elastic strength and coordination.

The Long Game: What Success Actually Looks Like

Steve Magness’s research on elite athletes reveals a pattern: “Data for elite female 5K runners shows that before they made their big breakthrough to the Olympian level, most of their times stagnated for two or three years.”

This is normal. This is expected. The 8th grader who runs 5:25 for the mile might run 5:20 as a freshman, 5:28 as a sophomore (growth spurt!), and then 4:55 as a senior after their body settles and accumulated training kicks in.

Parents see the plateau and panic. Your job is to normalize it. “He’s growing four inches. His body is adapting. This is exactly what’s supposed to happen.”

The Immediate Action Plan: What to Do NOW

If you’re coaching middle schoolers or early high schoolers with talent, here’s your playbook:

- Meet with Parents Use the script above. Set expectations. Educate on long-term development.

- Assess Movement Quality Watch them run at an easy pace. Look for efficiency, not speed. Identify 2-3 form cues to work on.

- Establish the Culture Talented kids thrive in positive environments. Make practice fun. Celebrate effort, not just results.

- Create Individual Development Plans Even talented 13-year-olds need custom approaches. Don’t cookie-cutter the training.

- Protect Them From overtraining. From parental pressure. From their own enthusiasm. Your job is to get them to 18 healthy and still loving the sport.

Talent is everywhere. It’s hiding in gym classes, playing soccer, shooting hoops, bussing dishes, playing video games, doing literally anything except organized running.

Your job isn’t to find the next superstar. Your job is to create an environment where ordinary kids become extraordinary athletes through patient, intelligent development. Where the late bloomers have permission to bloom late. Where the early developers don’t burn out before high school.

Youth coaches are the most important coaches in the entire pipeline. We build the foundation. We either protect young talent or destroy it. Choose wisely.

Related Resources:

→ Complete Guide to Coaching High School Distance Runners

→ Building a Culture of Excellence in High School Running

→ Managing Parents: Communication Strategies That Work

→ Race Strategy: Teaching Athletes to Compete Smart