The Guide to Freshman Mileage

Many high school coaches are so terrified of “breaking” a freshman that they accidentally train them to be slow forever.

They treat 14-year-olds like fragile porcelain dolls, capping them at 15 miles a week of junk mileage, terrified that a long run will snap a growth plate. The reality? Volume is rarely the killer; intensity is. If you want a freshman to reach their senior year potential, you don’t shield them from mileage—you teach them how to progress safely.

🔑 Key Takeaways for Freshman Mileage

- Assess History Don’t use Chronological Age; use “Running Age” (sports background).

- Mandatory Strides Perform 4–6x strides (20 sec) 2–3 times a week to fix mechanics.

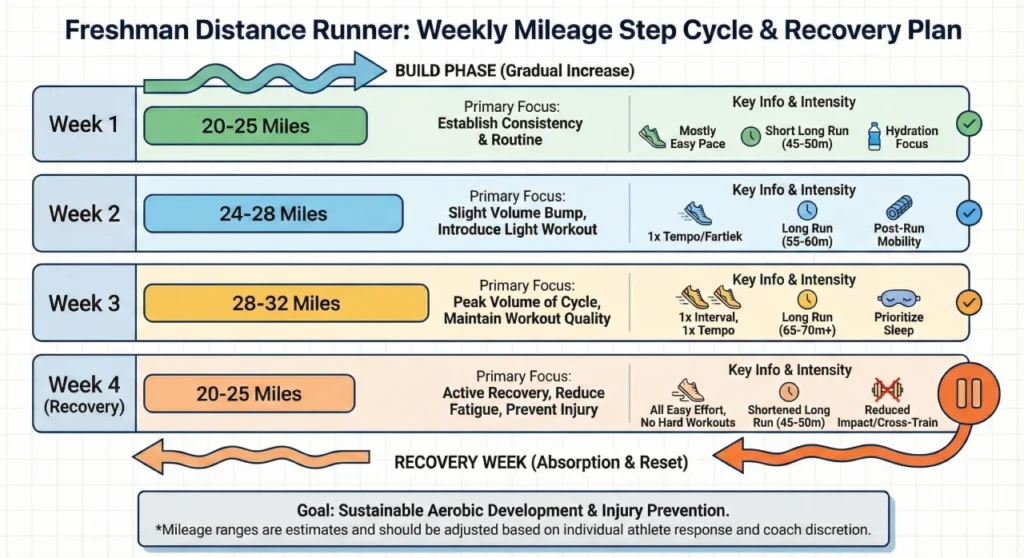

- Step Cycles Use a 3-week progression with a recovery week (e.g., 20mi, 22mi, 24mi, 20mi).

- Consistency Frequency (days per week) comes before volume (miles per day).

1. The Metric That Matters: Running Age vs. Chronological Age

The single biggest mistake coaches make is looking at a birth certificate to determine training volume. You must look at Running Age (Training Age) and Background Aerobic Age.

- Scenario A: The “Soccer” Freshman

- Profile: Has played competitive soccer or lacrosse for 6+ years.

- Physiology: High Aerobic Age, low skeletal durability. Their lungs say “Go,” but their shins say “No.”

- Progression: Faster aerobic ramp-up, but strict caps on pavement pounding.

- Scenario B: The “Couch-to-5K” Freshman

- Profile: No sports background, sedentary lifestyle.

- Physiology: Low aerobic floor, low durability.

- Progression: The long term approach—patience. Frequency before volume. 4 days becomes 5, then 6.

- Scenario C: The “Burnout” Transfer

- Profile: Ran youth track/AAU since age 8.

- Physiology: High Running Age, high burnout risk.

- Progression: They don’t need more mileage; they need different stimulus.

2. The Secret Sauce: Strides & Neuromuscular Hygiene

If you only run slow, you learn to be slow.

Freshmen who run nothing but easy mileage develop what I call “The Shuffle”—hips drop, knees barely lift, and ground contact time increases. You are effectively training them to be inefficient.

Why Strides Are Mandatory (Not Optional):

- Neuromuscular Wiring: Running long runs uses slow-twitch fibers. Strides force the brain to recruit fast-twitch fibers even in a fatigued state. This doesn’t make the athlete a sprinter; it makes their cruising speed efficient.

- Mechanical Efficiency: You cannot “cue” good form at 9:00/mile pace. You have to run fast to force the body to organize itself. Strides naturally fix mechanics: the athlete gets up on their toes, hips drive forward, and arms sync up.

- The Lydiard/Canova Connection: Lydiard insisted on “wind sprints” during base phase to keep the nervous system sharp. Canova uses “Alactic Sprints” to improve the chassis without taxing the engine.

The Saltmarsh Prescription:

- The Rest: Full recovery. Walking back to the start. If they are breathing hard when they start the next one, it’s an interval workout, not a neuromuscular drill.

- When: 2–3 times a week, after an easy run. Never on recovery days.

- The Protocol: 4-6 x 100 meters

- The Pace: Accelerate to 95% speed (fast, but relaxed). Not a max effort sprint. If they are straining their face, they are doing it wrong.

Applying the Masters to 9th Graders

We don’t reinvent the wheel; we just scale it down.

- The Lydiard Foundation: Arthur Lydiard proved that aerobic development is a lifetime project. For a freshman, we aren’t building a pyramid for this season; we are laying the concrete slab for their Senior year. The “Long Run” is non-negotiable. Even for a freshman, building up to a 60-minute run (at conversational pace) does more for their future physiology than any amount of 400m repeats.

- The Jack Daniels Consistency: Daniels emphasizes training at the right VDOT (current fitness), not goal fitness. Freshmen often run their easy days too hard (Category 3 pacing). You must force them to run slow to run long. If they can’t hold a conversation, the mileage doesn’t count.

- Canova’s “Extensive to Intensive”: Renato Canova teaches us to extend the ability to run longer before we run faster. Before you increase the speed of a tempo run, increase the duration of the tempo run.

4. Special Considerations: Boys vs. Girls

You cannot coach them identically during puberty.

- The Freshman Boy:

- Risks: Testosterone surges lead to aggressive running and “ego miles.” They will try to race their easy runs.

- Adjustment: Strict pace enforcement. Use heart rate monitors or the “talk test” relentlessly.

- The Freshman Girl:

- Risks: The Q-angle (hip width) changes, affecting knee mechanics. Bone density issues are real if nutrition isn’t tracking with energy expenditure (RED-S).

- Adjustment: Focus heavily on posterior chain strength (glutes/hips) to support the mileage. If a girl grows tall rapidly, plateau the mileage until coordination catches up.

5. The Practical Progression Models

Forget the generic “10% Rule.” It’s too linear. Use Step Cycles.

Coach Saltmarsh’s Golden Rule: Never increase volume and intensity in the same week. If you add intervals, cut the mileage.

Final Recommendation for Coaches

Stop looking at mileage as a risk and start viewing it as an investment account.

- Be Patient: It takes 6–8 weeks for the cardiovascular system to adapt, but months for tendons to catch up.

- Be Individual: The 14-year-old girl who grew 3 inches this summer has different needs than the 14-year-old boy who hasn’t hit his growth spurt.

- Be Consistent: A freshman who runs 25 miles a week for 12 weeks beats the freshman who runs 40 miles for 3 weeks and spends the rest in the pool.

Build the engine first. The chassis comes later.

For a tool that does the math for you and customizes these progressions based on the athlete’s specific season length use my Mileage Progression Tool. For a complete Summer Training Plan use my Summer XC Plan Generator.