High School Cross Country Training: The Complete Coaching Guide

By Coach Saltmarsh

High school cross country is a unique physiological and psychological puzzle. You have four years to take an adolescent—often physically immature and mentally (err..) developing—and turn them into an aerobic machine capable of racing 5,000 meters at their absolute physiological limit.

Unlike collegiate or professional coaching, where the athletes are selected, high school coaching is about development. We don’t just recruit talent; we build it.

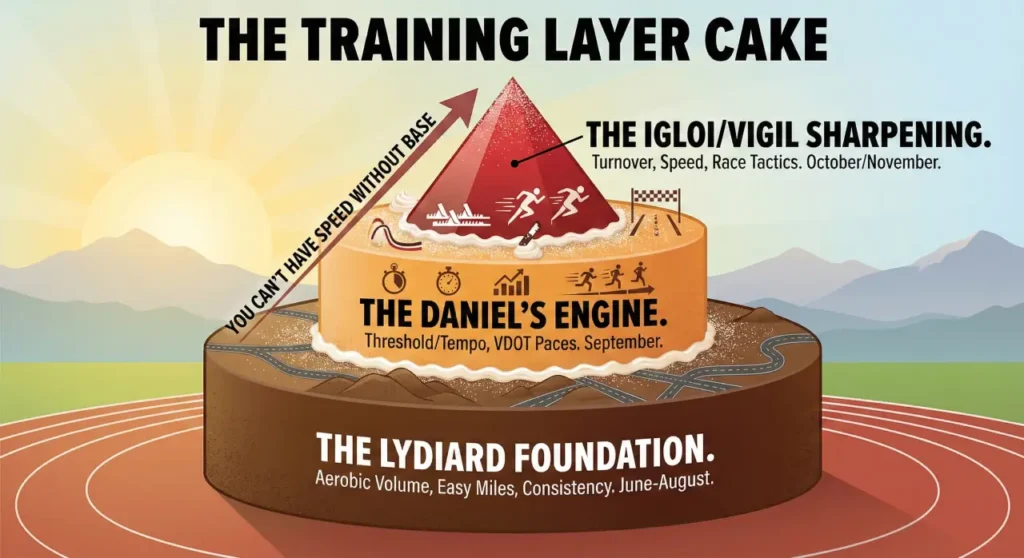

This guide represents a synthesis of the most effective training methodologies in history—Arthur Lydiard’s base building, Jack Daniels’ VDOT precision, Mihály Iglói’s interval structures, and Joe Vigil’s scientific peaking—adapted specifically for the 14-to-18-year-old runner.

Whether you are a veteran coach looking to refine your periodization or a new coach building a program from scratch, this is your blueprint for the season.

Part 1: The Philosophy of the High School Season

Before we discuss mileage or split times, we must agree on the goal. In high school cross country, the goal is not to win the workout. The goal is to run the fastest possible time at the Championship Meet in late October or early November.

Every run, every lift, and every recovery day must serve that specific endpoint.

To do this, we borrow from the masters:

- The Lydiard Influence: We accept that aerobic development takes years, not weeks. We prioritize volume (relative to age) over intensity in the early season.

- The Daniels Influence: We use physiological data (VDOT) to ensure we are training the correct energy systems, not just “running hard.”

- The Vigil Influence: We teach that “physiology is psychology.” A runner cannot hurt enough to win if they do not have the character to endure it.

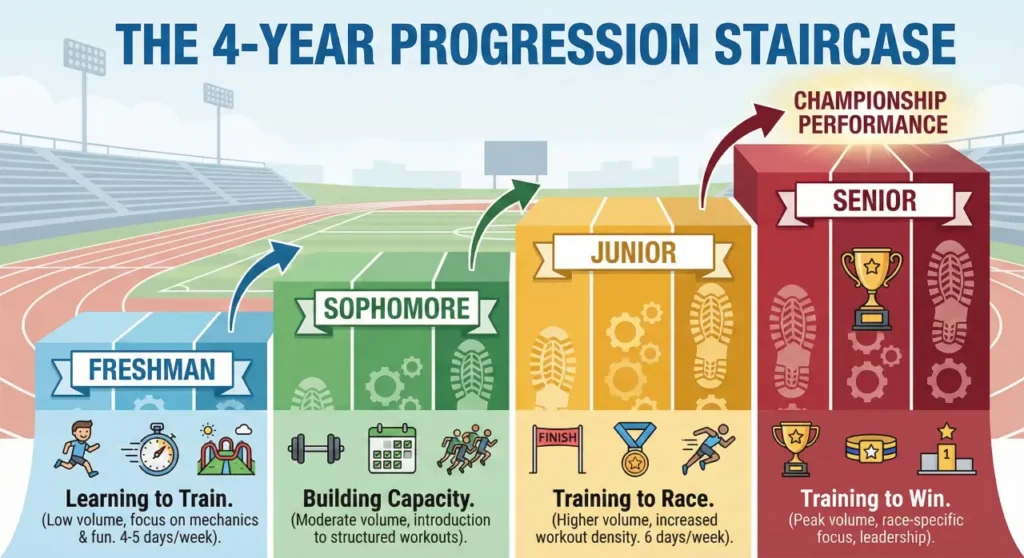

The 4-Year Progression

The biggest mistake I see in high school coaching is treating a freshman like a senior. A 14-year-old boy or girl does not have the skeletal maturity or aerobic capacity of an 18-year-old. I’ve made this mistake during lean years when we just didn’t have the numbers and regretted it.

If you throw a freshman into a senior’s 50-mile week, you don’t get a faster freshman; you get a stress fracture. We must view training as a four-year staircase. Here is the comprehensive guide on progressive mileage for high schoolers.

Part 2: The Foundation (June – August)

“Miles Make Champions”

Arthur Lydiard famously said, “Miles make champions.” For the high school runner, the summer is where the season is won or lost. You cannot cram aerobic fitness in September. The physiological adaptations required to process oxygen efficiently—capillary density, mitochondrial biogenesis, stroke volume—require months of steady-state running.

However, “just run” is dangerous advice for a teenager. We need structured aerobic development.

The Role of Summer Training

Summer training should be 90% aerobic. The pace should be conversational. The focus is on consistency and frequency.

- Freshmen: 4-5 days a week. Focus on learning to love the run.

- Varsity: 6 days a week. Focus on increasing the long run.

The summer is also where we introduce the “Long Run”—the single most important run of the week. Ideally, this constitutes 20% of the weekly volume.

Injury Prevention During Base Phase

The risk of high mileage is overuse injury: shin splints, patellar tendonitis, and stress reactions. The culprit is rarely the distance itself, but the rate of increase. We follow the 10% rule loosely, but more importantly, we listen to the body. Everything you need to know about building safe summer base mileage.

Part 3: The Science of Periodization (JULY – NOVEMber)

Structuring the Season

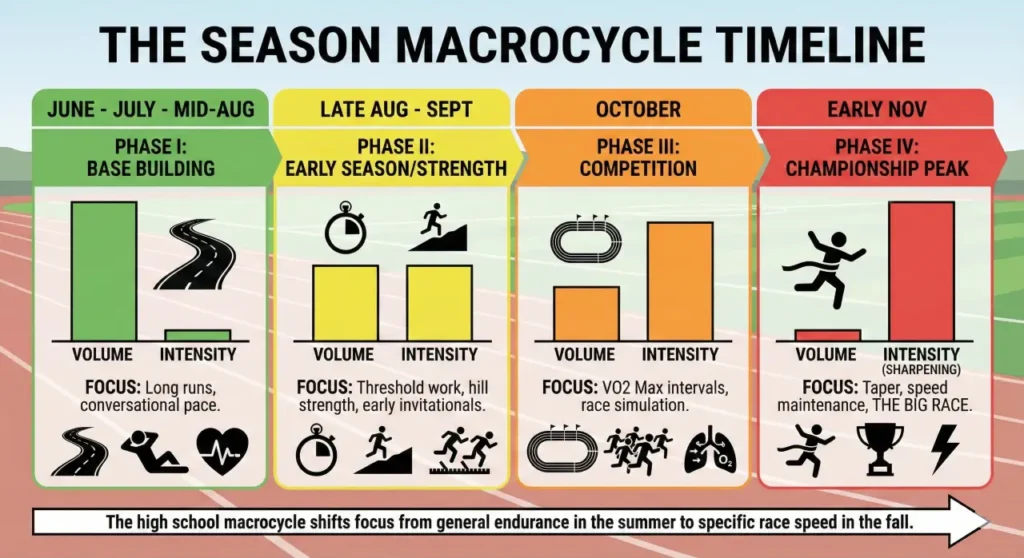

We cannot hold a peak forever. This is where Periodization comes in. We divide the season into distinct phases (Mesocycles), shifting our focus from General Endurance to Specific Endurance. Read more with our guide to designing training mesocycles.

- Phase I (Base): High volume, low intensity. (Summer)

- Phase II (Early Season): Moderate volume, introduction of Threshold. (September)

- Phase III (Competition): Maintenance volume, high intensity (VO2 Max). (October)

- Phase IV (Peaking): Low volume, high intensity. (November)

Adapting this for high schoolers is tricky because they race almost every week. We have to train through the dual meets, using them as workouts, rather than tapering for every Wednesday afternoon race. Or, we can choose to focus on a schedule made up of invitationals and cherry-pick our race days. Either way, you must adhere to the science of periodization and macrocycles.

Part 4: The Workouts (The “Meat” of Training)

The Daniels Approach: Threshold is King

If Lydiard owns the summer, Jack Daniels owns September. The most critical energy system for a 5k runner is the Lactate Threshold (roughly the pace you can hold for 60 minutes, or “comfortably hard”).

For high schoolers, we call these “Tempo Runs.”

- The Workout: 20 to 25 minutes at Threshold Pace (T-Pace).

- The Benefit: It pushes back the point at which lactic acid accumulates in the blood, allowing the runner to run faster for longer without fatigue.

The Igloi Influence: Rhythm and Intervals

Mihály Iglói taught us that not all intervals need to be gut-busting sprints. “Fresh” intervals—short repetitions with short rest—can build mechanical efficiency and speed without destroying the legs. We use these early in the season to keep the legs snappy while mileage is high. Want more specifics, check out these 3 Essential High School XC Workouts.

Calculating the Paces

You cannot guess these paces. A Tempo run run too fast is a race; run too slow, it’s junk mileage. We use race data or time trials to determine training paces. This is the only way to ensure that your athletes are getting exactly what they should in terms of training stress from every workout.

Use our free Training Pace Calculator to determine the exact Threshold pace and Easy pace for every runner on your team based on their most recent 1-mile or 5k time.

Training Paces

Part 5: Race Day and Tactics

The Mental Game

Coach Joe Vigil emphasizes that the distance runner must be "the toughest athlete in sports." But toughness is a skill, not a trait. We teach our athletes to dissociate from the pain during the middle mile and associate with the competition during the final mile. Younger athletes tend to measure their success by how they do versus their teammates. Reluctant competitors are satisfied measuring their success based on past performances. Champions understand that racing is about winning.

Managing the Race Week

How do you balance a hard Tuesday workout with a Saturday invitational? The structure of the practice week is critical.

- Monday: Long Run

- Tuesday: Quality Workout (Threshold or VO2 Max)

- Wednesday: Recovery Run

- Thursday: Pre-Meet (Neuromuscular activation -shorter, faster)

- Friday: Shakeout

- Saturday: RACE

- Sunday: Rest or Recovery (depending on athlete)

Structuring the perfect 2-hour practice A daily guide to organizing your week for maximum recovery and performance.

Part 6: The Championship Phase (Late October - November)

The Art of the Taper

The work is done. You cannot get fitter in the last 10 days; you can only get fresher. The goal of the taper is to shed fatigue while maintaining aerobic tension.

Many coaches make the mistake of dropping intensity and volume. This leaves legs feeling "flat."

- Rule of Thumb: Drop the volume (mileage), but keep the intensity (pace) high. The workouts get shorter, but the speed stays fast.

Championship Tactics

Championship racing is different from dual meets. The fields are larger, the start is faster, and the adrenaline is higher. We prepare our athletes for "The Funnel"—the narrowing of the course 400m in—and how to manage the adrenaline and nerves in the first mile so they don't crash in the third.

Need help scoring a home meet? Use this FREE XC Meet Scoring Calculator for all of it.

Summary: The Coach's Responsibility

Coaching high school cross country is a privilege. We are teaching young people how to set a goal that is months away and work toward it every single day. By combining volume, precision, and passion, we give our athletes the best possible chance to succeed—not just on the course, but in life. Read my case study on building a championship season.

Ready to Plan Your Season Now?

Don't start from scratch. I’ve built a 12-week XC season training template that scales for Varsity and JV runners. Always FREE for subscribers. Check it out!

About the Author

Coach Saltmarsh is a high school distance coach and educator focused on bringing elite sports science to the high school level. His tools and training plans are used by coaches across the country to simplify the math of training and develop successful distance runners.