Why We Need to Stop Coaching High School Runners Like Robots

Featuring OLYMPIC insights from Coach Mike Scannell

Look, I’m going to be straight with you. We’ve got a problem in high school distance running, and it’s not what you think. It’s not a lack of talent or “soft kids.” It’s us—the coaches. We are so busy following our beautiful, color-coded training plans that we’ve forgotten to actually look at the human beings standing in front of us.

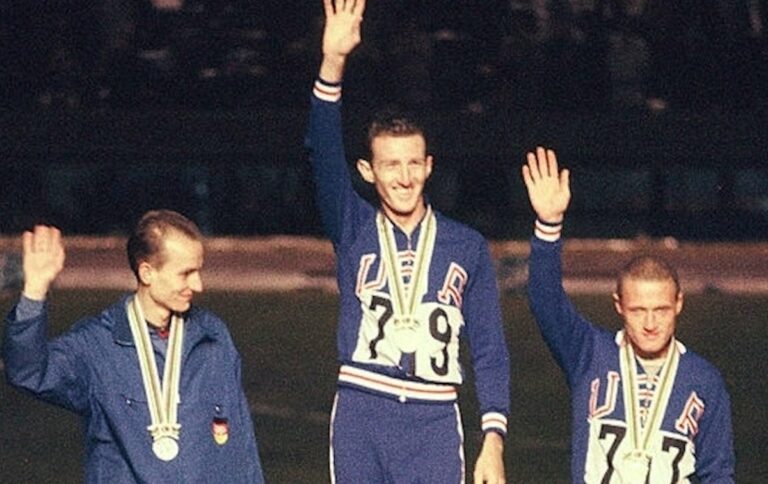

When Mike Scannell coached Grant Fisher to two Olympic medals, he didn’t do it by being a dictator. He did it by being a “passenger in the car.” Grant was always in the driver’s seat.

If we want our runners to reach their potential—whether that’s a State PR or an Olympic podium—we have to stop being drivers and start being mechanics.

The Problem: We’re Building Robots, Not Runners

Most coaches read the books—Daniels, Lydiard, whoever—and build “perfect” periodized plans packed with proven methodologies. We show up to practice and expect teenagers to execute them like clockwork. This is the danger of being information rich and experientially poor.

Teenagers aren’t predictable. They aren’t always responsible. And, they naturally resist being told what to do. They are seventeen-year-olds taking four AP classes, working part-time, and running on five hours of sleep. Your spreadsheet doesn’t account for the poor chemistry test, the falling out with a friend at lunch that day, or the fact that they’re “cooked” before they even start their warm-up.

As Coach Scannell points out, the system often “chews kids up and spits them out” because it values the plan over the person. When kids feel like interchangeable parts in your system, they often quit.

The Solution: The “Mechanic” Philosophy

Coach Scannell views the coach-athlete relationship as a professional partnership. He famously told Grant Fisher: “I will help, but you will drive. You’re the race car driver; I’m just the mechanic.”

Giving athletes agency doesn’t mean letting them do whatever they want. It means creating a collaborative environment where you coach with them, not at them. Here is how to implement that “Mechanic” mindset using three transformative questions:

Question One: “How are you feeling today—really?”

This is assessment, not small talk. Scannell uses high-tech tools like lactate analyzers to target specific blood values (like 3.8 to 4.0 mmol/L) to gage the impact of a workout. I can’t afford that- even if it was something my school district would let me do. (They won’t.) Thankfully for those of us without high tech tools, Scannell admits the “art” of coaching is looking an athlete in the eye.

- The Science: You might not have a lactate meter, but you have eyes. Is their form breaking down? Are they especially irritable? Are their shoulders slumped? Do they look beat up long before they should be?

- The Art: Ask about their sleep and stress. If an athlete is sick or over-stressed, their “numbers” won’t match the plan. Scannell notes that if an athlete isn’t “absorbing the training,” you’re just digging a hole.

Question Two: “Do you sign off on this plan?”

Scannell doesn’t just hand his athletes a workout; he sits down with them to discuss the philosophy behind the volume and intensity. He believes that at every level, an athlete must believe the work they are doing is what will get them to the podium. This is crucial. I meet with my teams once a week to go over the training plan and answer questions.

Before the season or a big block of training, show them the “why.” Ask them: “Does this make sense to you? Are you on board?” When an athlete signs off on a plan, they take ownership of it. They aren’t just following orders; they are executing a strategy they helped build.

Question Three: “How can I mirror your motivation?”

Not every kid wants to be Grant Fisher. Some want to win States; others just want to be part of a team. Scannell’s rule is simple: Mirror the athlete’s motivation. This is a lesson that I still haven’t mastered. I always want to see an athlete reach their potential. I have to remind myself that my goals for an athlete cannot, and will not, change the goals that exist in the head of the athlete.

As a coach, you are a mechanic. You are not a motivator. You might provide short term excitement or a boost in confidence, but if it doesn’t come from within, it isn’t going to last. Let the athletes tell you what they want and help them get there.

- If a runner comes to you asking for more work or recovery tips, give them 100% of your expertise.

- If a runner just wants to participate, show them what being a good participant looks like.

- Don’t tell them what they can’t do. Scannell warns that we should never set limits on kids, because “high school kids don’t know what they can’t do” until we tell them they can’t.

Practical Strategies for high school coaches

1. Adjust Immediately, Not Later

Don’t wait for the next day to fix a bad workout. If the wind is 20mph or the heat is 90 degrees, Scannell adjusts the pace or the rest within seconds. If the “mechanic” sees the engine is overheating, he pulls the car over. He doesn’t tell the driver to finish the lap and hope the engine doesn’t blow.

2. The 30-Second Check-In

You don’t need a PhD or a lactate meter to be a great coach. You just need to be present. Pull an athlete aside for 30 seconds. Ask: “What do you need from me right now to help you perform your best?”

As Coach Scannell says, we don’t just “get” fast runners; we make them by fostering their existing internal motivation. The next time you face a runner who seems “off,” resist the urge to push the spreadsheet and make them feel heard.

Ask. Listen. Respond. That’s how you develop not just faster runners, but better humans.

Watch the full interview with Mike Scannell on the B.rad Podcast here.