How to Build Base Mileage Without Getting Injured

It’s the Fourth of July. The local 5K just finished. I see my breakout sophomore limping. Don’t be a casualty of the ‘June Jump.’ Here is the veteran coach’s guide to navigating summer mileage.

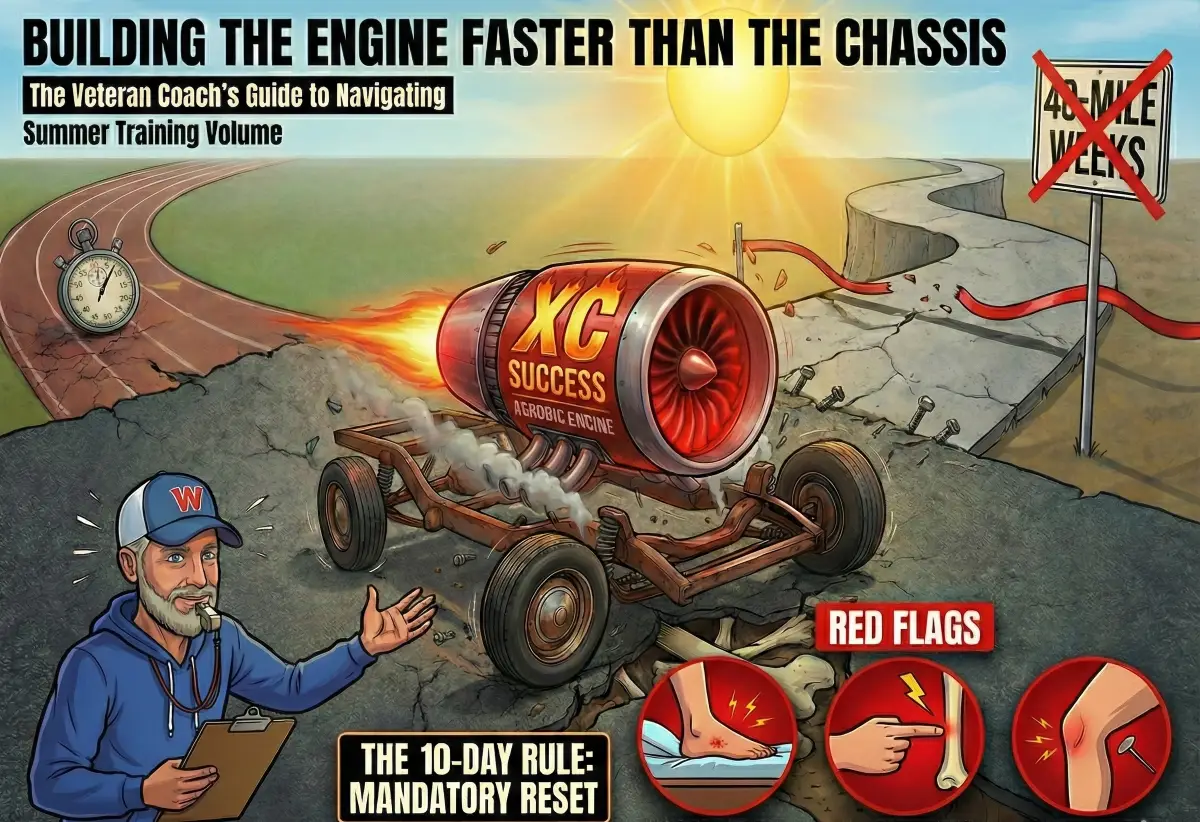

Building a massive aerobic engine is crucial for XC success—we all know the science. But if you build the engine faster than you build the chassis, the car shakes itself apart. Here is a veteran coach’s guide to successfully navigating summer training volume without blowing up your fall season.

This article is part of our Complete Guide to High School Cross Country Training, which covers everything from seasonal planning to race day tactics.

The 10-Day Rule

In my program, we have a non-negotiable law for the transition between seasons: The 10-Day Rule. It’s mandatory. All my runners to take a full 10-day break from running after track season ends. Cross-training like biking, swimming, or surfing is fine to keep active, but the body and mind desperately need a hard reset from the repetitive impact of running.

I learned the value of this years ago while sharing a cab ride in New York City with Gwen Jorgensen. This was before her 2016 Olympic Gold in the triathlon, but her mindset was already championship level. As I chatted nervously about my upcoming NYC marathon and future racing plans, she offered a piece of advice I’ve never forgotten: time away from the sport is essential. She revealed that she took an entire month completely off every year to recuperate. Her philosophy was clear: without scheduled downtime, gains diminish, and burnout is inevitable.

Consider the typical high school distance runner in early June from a physical standpoint. They are a finely tuned speed machine, running relatively low volume—perhaps 20 to 25 miles a week—at incredibly high intensity. Crucially, most of this work happens on a rubberized track that acts like a trampoline, forgiving the legs and returning energy with every stride. They have just tapered and peaked for their target races. That needs to be respected and considered at the macrocycle level. Each season is an extension of the one before.

Furthermore, we cannot ignore the immense psychological toll of this transition period. By late May, student-athletes have just endured the highest-pressure phase of their year—peaking for championship meets while simultaneously navigating final exams and end-of-year academic stress, prom proposals and summer job interviews. They are emotionally tapped out. To ask them to immediately pivot from that finish line and stare down the barrel of a new, grueling six-month training block for cross country is nuts. The psychological tank is often emptier than the physical one; without a genuine mental reset, burnout by October isn’t just a possibility, it’s a guarantee.

Despite this obvious physical and mental fatigue, the pressure to become a “serious” XC runner by racking up big summer miles is there. Too often, athletes jump straight onto unforgiving concrete sidewalks to log 40-mile weeks. It is important to remember that the cardiovascular system adapts quickly to this new volume. However, connective tissue—tendons, ligaments, fascia, and bone—adapts slowly. It takes months, not weeks, to adapt to the repetitive trauma of road running.

When your lungs say “Go” but your bones and brain say “No,” injury is the inevitable outcome. Instead of obsessing over an immediate ramp-up, athletes need to recharge their batteries first. Take the break. The miles will be there when you get back.

The Philosophy: “Earning” the Miles

Before we look at the red flags, you need to adopt a new mantra for the summer: Volume is earned, not given. You don’t get to run 50 miles a week just because you’re a junior now. You run 50 miles a week because your body successfully handled 45 miles for three weeks straight without a whisper of injury. If you can’t run 30 miles a week feeling good, 40 miles won’t make you faster; it will make you injured.

The 3 “Red Flags” You Must Never Ignore

High school runners are masters at lying to themselves about pain. You think pushing through pain makes you tough. Listen to me: Running through a side stitch is tough. Running through a stress reaction is stupid.

You need to know the difference between “good sore” (training adaptation) and “bad sore” (injury onset).

Red Flag #1: The Morning Hobble (Achilles/Plantar)

You wake up, put your feet on the floor, and your first three steps make you wince. Your heel feels bruised, or your Achilles tendon feels like a prickly cable. Once you walk around for ten minutes, it loosens up and feels fine.

- The Verdict: This is the early warning system for plantar fasciitis or Achilles tendinopathy. Your tendons are inflamed and tightening up overnight.

- The Action: Do not run through the morning hobble. If it takes 10 minutes to loosen up today, it will take 20 next week. Cut mileage. Eccentric heel drops become your new best friend.

Red Flag #2: Pinpoint Bone Pain (The Finger Test)

General soreness usually covers a broad area—your whole quad aches, or your entire shin feels tight. That’s usually muscular fatigue or “shin splints” (medial tibial stress syndrome).

But if you can take your index finger, press on one specific, dime-sized spot on your shin, foot, or femur, and it sends a jolt of sharp pain right to your stomach?

- The Verdict: Stop running immediately. Do not try a “test jog” tomorrow. That is a stress reaction, the precursor to a full fracture.

- The Action: See a doctor. You need an MRI or bone scan. If you catch a stress reaction early, you might miss two weeks. If you run on it until it cracks, you miss two months.

Red Flag #3: The Unilateral Ache (One-Sided Pain)

If both knees are a little achy after a hilly long run, that’s normal wear and tear.

If your left knee feels great, but your right knee feels like there’s an icepick under the kneecap every time you go down stairs?

- The Verdict: Asymmetry is never good. It means your gait is off, or you are compensating for weakness somewhere else in the chain (usually hips or glutes).

- The Action: Reduce volume and get to a physical therapist to find the imbalance before it blows out a joint.

The Practical Transition Plan

Phase 1: The Reset (1-2 Weeks after Track ends) Do not run. Seriously. Your body has taken a beating for six months. Take 7 to 14 days completely off running. Swim, bike, hike, play basketball. Let the micro-trauma heal. You will not lose fitness; you will gain longevity.

Phase 2: The Re-Entry (Late June) Start at 50% of your peak track mileage. If you ended track running 30 miles a week, your first week back is 15 miles. All easy effort.

Get Off the Concrete. Your bones hate concrete. It has zero give. Find grass parks, dirt trails, or cinder paths for at least 50% of your summer mileage. The softer surface reduces the impact force significantly, allowing you to log more miles with less skeletal stress.

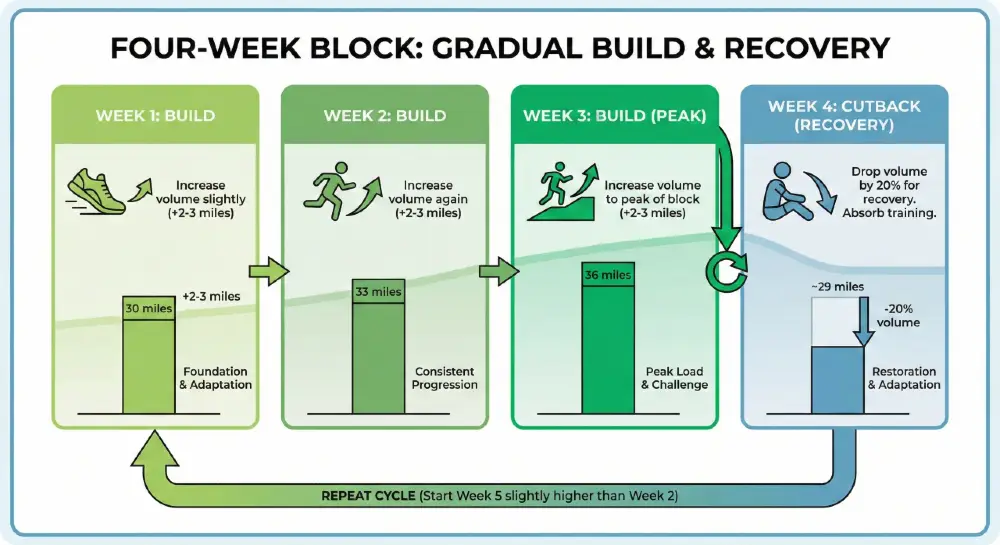

Phase 3: The Gradual Climb (July) Use the “Four-Week Block” method:

- Build Week 1: Increase volume slightly (e.g., add 2-3 miles total to the week).

- Build Week 2: Increase volume slightly (e.g., add 2-3 miles total to the week).

- Build Week 3: Increase volume slightly (e.g., add 2-3 miles total to the week).

- Cutback Week 3: Drop volume by 20% for a recovery week to absorb the training.

- Repeat, starting Week 5 slightly higher than Week 2.

Need help planning this? Use our free Summer Training Generator to build a safe progression.

The Long Game

September is a long way off. Nobody wins a state championship in July, but plenty of people lose one because they are either doing too much or too little.

Be patient. Watch for the red flags. Build the chassis strong enough to handle the engine you’re developing. Keep the athlete’s long-term development in mind. Refer to our age-based mileage guidelines. If you can stand on the starting line in August healthy, consistent, and injury-free, you’re already ahead of half your competition! And remember, with the heat and humidity, it’s not easy some days. Give yourself a break as needed.

Now that you know how to build base mileage safely, find out how to design the next phase of training with our Guide to Periodization Training