The Complete Guide to Coaching High School Distance Runners

After two decades coaching high school cross country and track, including multiple state championships and dozens of All-State performers, I’ve learned something crucial: the difference between average programs and exceptional ones rarely comes down to talent. It comes down to coaching that understands both the science and the soul of adolescent development.

I spent years studying exercise physiology, dissecting training methodologies, and analyzing VO2max charts. But the real breakthrough in my coaching came when I stopped treating sixteen-year-olds like miniature college athletes and started understanding them as the rapidly developing, highly motivated, wonderfully complex young people they are.

This guide synthesizes what research tells us about coaching high school distance runners with what actually works in the unpredictable works in the unpredictable, resource-constrained, gloriously messy reality of high school coaching.

Understanding Your Athletes: More Than Just Numbers

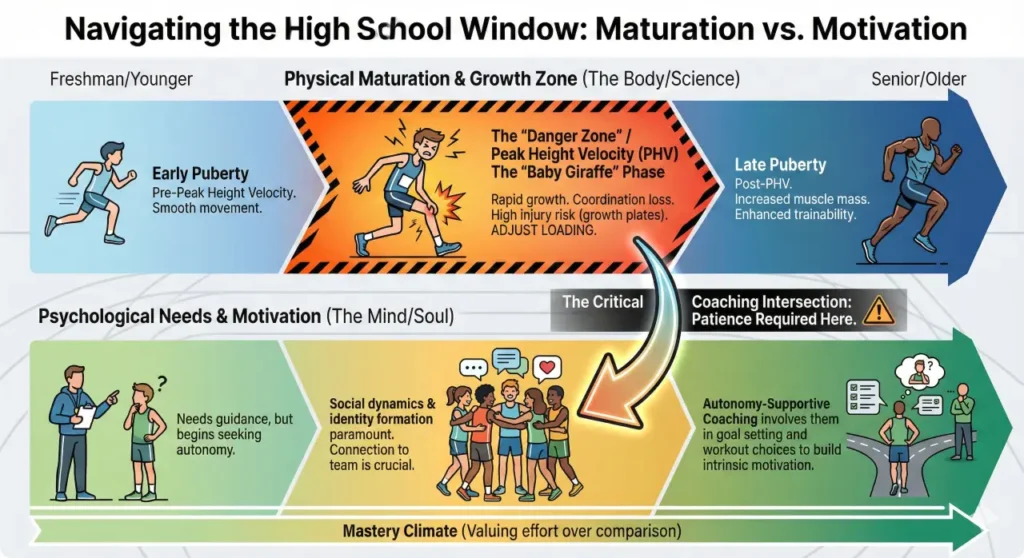

Before we discuss training zones or mileage progressions, let’s talk about who you’re coaching. High school distance runners exist in a unique developmental window. They’re experiencing dramatic physiological changes while navigating academic pressures, social dynamics, identity formation, and—in many cases—their first serious athletic commitments. And, well, let’s just say it… distance runners are different.

The research on adolescent athlete development consistently emphasizes that chronological age tells you surprisingly little. A freshman team might include a 14-year-old who hasn’t hit their growth spurt alongside a 15-year-old who’s biologically closer to 18. They cannot—and should not—train the same way.

The Maturation Dilemma

Peak height velocity (PHV) marks the period of fastest growth during puberty. For girls, this typically occurs around ages 11-13; for boys, 13-15. The year surrounding PHV is simultaneously the best and worst time for athletic development.

On one hand, hormonal changes dramatically enhance trainability. Muscle mass increases, aerobic capacity expands, and the neuromuscular system becomes more adaptable. On the other hand, this rapid growth creates temporary coordination challenges, increases injury susceptibility (particularly to growth plate issues), and can temporarily disrupt movement patterns that were previously smooth.

Smart coaches monitor for signs of rapid growth—sudden changes in shoe size, complaints about “growing pains,” temporary awkwardness in previously fluid runners—and adjust training accordingly. When a sophomore suddenly shoots up three inches over the summer, they need patience and modified loading, not your standard mileage progression. We sometimes refer to them as baby giraffes. Take it easy on them at that stage.

The Psychology Matters More Than You Think

Research on adolescent athlete motivation reveals something many coaches miss: controlling coaching behaviors—however well-intentioned—undermine long-term development and increase fear of failure. Autonomy-supportive coaching, where athletes are given appropriate decision-making power and their psychological needs are respected, produces more resilient, intrinsically motivated runners. I find this to be especially evident with girls.

What does this look like practically? It means involving athletes in goal-setting conversations rather than simply imposing targets. It means explaining the “why” behind workouts rather than demanding blind obedience. It means recognizing that a runner’s sense of competence, autonomy, and connection to teammates profoundly affects their training response.

The coach who creates a mastery climate—where improvement and effort are valued over comparison with others and ‘winning at all costs’—develops athletes who remain engaged with running long after high school. The coach who emphasizes only performance outcomes and peer comparison may produce short-term results but often at the cost of burnout, injury, alienation, or early sport dropout.

The Foundation: Building the Aerobic Engine

Distance running, from the 800m to the 5K, is overwhelmingly aerobic. Even the 800m derives approximately 60-70% of its energy from aerobic metabolism. This fundamental truth should drive your training philosophy.

The 80/20 Principle (Or Close to It)

Elite distance runners worldwide, across all events from 5,000m to the marathon, perform approximately 80% or more of their training volume at low intensity. This isn’t recreational jogging—it’s deliberate, consistent aerobic development at paces well below race intensity. And, low intensity translates to easy pace. But, let’s be careful about what we call easy in front of the athletes. You may want to replace easy with ‘regular’ in your working vocabulary.

For high school runners, this means most training should occur at comfortable conversational pace. If your athletes can’t maintain a conversation during their regular daily runs, they’re training too hard too often.

Why does this matter? Because the aerobic adaptations that make runners faster—increased mitochondrial density, enhanced capillary networks, improved fat oxidation, greater stroke volume—develop best through sustained, moderate-intensity training. Runners who constantly push threshold or VO2max paces during “easy” runs chronically elevate their stress hormones, accumulate excessive fatigue, and ultimately develop more slowly than athletes training more patiently.

I’ve seen this happen. I coached a state champion a few years ago. She was always running with the slowest group on recovery days and was the last one to finish the warm up laps. But, on race day, especially when it mattered most, she was faster than anyone else! She wasn’t being lazy on the recovery days, she was being very smart.

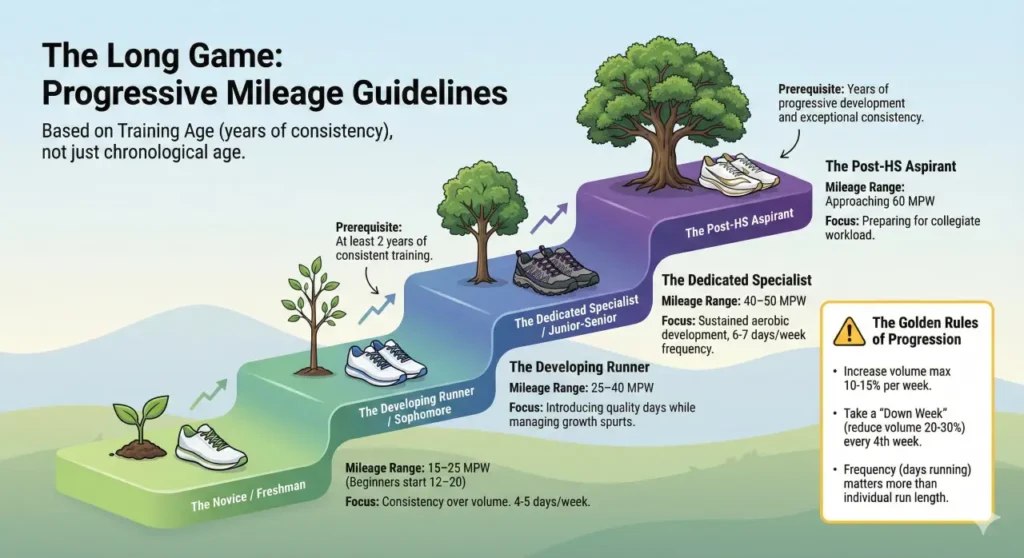

Mileage Progression: The Long Game

How much should high school distance runners run? The answer frustrates coaches seeking definitive numbers, but it’s genuinely individualized. Research on youth athlete development emphasizes progressive loading matched to training age (years of consistent training) rather than chronological age. A freshman with three years of middle school running background can handle more volume than a senior novice.

General guidelines I’ve found effective:

Freshmen: 15-25 miles per week during competitive season. True beginners might start even lower—12-20 miles weekly—with emphasis on consistency over volume. Beginning at just 4 days a week.

Sophomores: 25-40 miles per week. Athletes should have at least two full years of consistent training before pushing beyond 40 weekly miles.

Juniors/Seniors: 40-50 miles per week for dedicated distance specialists. Runners pursuing post-high school competition might extend toward 60, but this requires years of progressive development and exceptional consistency.

Two critical principles: First, increase weekly volume no more than 10-15% per week, and include periodic down weeks (reducing volume by 20-30%) every 4th week. Second, athletes should run 6-7 days per week rather than cramming mileage into fewer, longer runs. Frequency matters more than individual run length for developing aerobic fitness while managing injury risk. Hammering out a single long run is satisfying to the Strava ego, but not the smart thing to do.

Easy Runs Are Not Junk Miles

Many coaches struggle with truly easy running. They intellectually understand it but instinctively feel their athletes should “push themselves” more. This misses the point entirely. It’s not a question of toughness or desire. It’s having the discipline to run the workout as intended that matters most.

Easy runs serve multiple essential functions: they add training volume without excessive stress, promote recovery between hard sessions, develop fat oxidation and metabolic efficiency, and build the capillary networks that deliver oxygen to working muscles. None of these adaptations require suffering.

I tell my athletes that easy runs should feel easy. If you’re constantly checking your watch to “make sure you’re not going too slow,” you’re missing the purpose. The goal is accumulating aerobic stimulus, not impressing anyone with training paces.

The Hard Days: Making Quality Count

If 80% of training is easy, what about the other 20%? This is where specificity enters, where we develop the physiological capacities to handle competitive racing over 5 kilometers.

Three Essential Workout Types

VO2max intervals develop maximum aerobic capacity—the engine’s ceiling. These are hard efforts at approximately current 2-mile race pace, typically lasting 3-6 minutes with equal or slightly shorter recovery. Classic examples: 6 x 800m at 3K pace, 5 x 1000m at 5K pace, 4 x 1200m at 5K pace.

The key? These should feel hard but controlled. If your runner is destroying themselves on the first interval and barely surviving the last, the pace is too fast or recovery insufficient. VO2max work requires 48-72 hours recovery before another hard session. Tuesdays work well if you have a Saturday meet.

Threshold runs target the metabolic boundary where lactate begins accumulating faster than it can be cleared—roughly current 10K race pace for trained runners, 10-mile to half-marathon pace for less experienced athletes. These sustained efforts, typically 20-40 minutes for high schoolers, teach the body to buffer and clear lactate more efficiently while improving running economy.

I prefer continuous tempo runs (20 minutes at threshold pace) for experienced runners and broken tempos (3 x 8 minutes with 2-minute recovery, or 2 x 12 minutes with 3-minute recovery) for developing athletes. The physiological stimulus is very similar, but broken tempos are psychologically more manageable.

Aerobic power workouts bridge easy running and threshold work—sustained efforts at moderate intensity that extend aerobic capacity without the sharp discomfort of threshold or VO2max training. Progressive long runs, where you start easy and gradually accelerate to moderate effort over the final 25-30% of the run, accomplish this beautifully while reinforcing the ABC (always be closing) mentality.

The Critical Balance: Recovery

Here’s what separates good coaches from great ones: understanding that adaptation happens during recovery, not during the workout itself. The workout is merely the stimulus. Growth occurs when the body repairs and rebuilds stronger than before (supercompensation).

High school athletes require more recovery than adults. Their bodies are simultaneously managing training stress and growth/maturation demands. Sleep requirements are higher (9+ hours ideally, though many fall short). Academic and social stressors compound physical fatigue.

The hard/easy microcycle—alternating difficult training days with genuine recovery days—isn’t optional. It’s physiologically mandatory. A typical training week might look like:

- Monday: Easy run

- Tuesday: VO2max intervals

- Wednesday: Easy run with strides

- Thursday: Threshold workout

- Friday: Easy run or complete rest

- Saturday: Long run (with aerobic power component if athlete is ready)

- Sunday: Easy run or rest

Notice only two truly hard sessions weekly. More frequent hard training doesn’t accelerate improvement; it accelerates breakdown.

Strength Training: The Missing Link

Distance running coaches often view strength training as “extra” or “if we have time.” This is a mistake. Research increasingly demonstrates that appropriate strength training enhances running economy, reduces injury risk, and improves sprint speed and power—all valuable for distance runners.

What Strength Training Should Look Like

Forget bodybuilding or powerlifting protocols. Distance runners need functional strength that supports running mechanics and protects against injury.

Effective strength programs emphasize:

Unilateral lower body work: Single-leg squats, split squats, step-ups, and single-leg deadlifts develop stability and address imbalances.

Posterior chain development: Deadlift variations, Nordic hamstring curls, and glute bridges strengthen the muscles that propel running forward and protect against hamstring strains.

Core stability: Planks, side planks, and dead bugs develop the anti-rotation and anti-extension strength that maintains efficient posture during fatigue.

Plyometric progression: Box jumps, bounding, and skipping drills develop the reactive strength and elastic recoil that improve running economy.

Strength sessions need not be lengthy—20-30 minutes, 2-3 times weekly is sufficient. The key is consistency and progressive overload, gradually increasing difficulty as athletes adapt.

Critically, strength training should complement, not compete with, running training. Schedule strength work after the run. During peak competition phases, maintain strength work but reduce volume to manage overall fatigue. Eliminate it entirely during the taper phase.

Race Strategy and Competition Development

Training develops fitness, but racing develops racers. How you prepare athletes for competition matters enormously.

Teaching Pace Judgment

Many young runners race terribly—not from lack of fitness, but from poor pace management. They surge with adrenaline through the first mile, suffer through the second, and survive the third. To make matters worse, losing ground in the last mile adds emotional defeat to physical exhaustion. Bookmark this link for later if you want to learn everything you need to know about mastering 5K race strategy.

Teach pace awareness through practice. Time trials at goal pace, with splits called every 400m, help athletes internalize what sustainable race pace feels like. Negative split long runs, where the final portion runs faster than the first, develop the discipline to start conservatively. Race simulation workouts—intervals at race pace with short recovery, mimicking the physiological and psychological demands of racing—prepare athletes for competition’s unique stresses.

I once had a team that didn’t understand the visceral effort required to win. In a move that broke my own rules about athlete comparison, I had them run 8x400s at the exact paces of our top league rivals. It was physiologically aggressive and psychologically risky, but it worked. It gave them a tangible definition of ‘fast.’ To this day, alumni still mention that workout—usually with a grimace—but it completely reset their racing expectations. Coaching is an art. Sometimes you just call an audible on the play because it feels right.

Developing Competitive Toughness

Racing hurts. This is non-negotiable. But there’s a difference between productive discomfort and destructive suffering.

Mentally tough athletes, research suggests, share common characteristics: they maintain control under pressure, stay committed despite setbacks, view challenges as opportunities rather than threats, and possess confidence in their preparation.

You develop these qualities not through motivational speeches but through structured experiences. Time trials where athletes practice race-day routines. Workouts where they finish strong despite fatigue. Challenging races where incremental improvement (pace, strategy, execution) matters more than placing.

Critically, create a mastery-oriented environment where athletes compare themselves to their previous performances, not their teammates or rivals. Runners who focus on personal improvement demonstrate greater resilience and sustained motivation than those obsessed with beating specific competitors. I remind them that “you can only control you.”

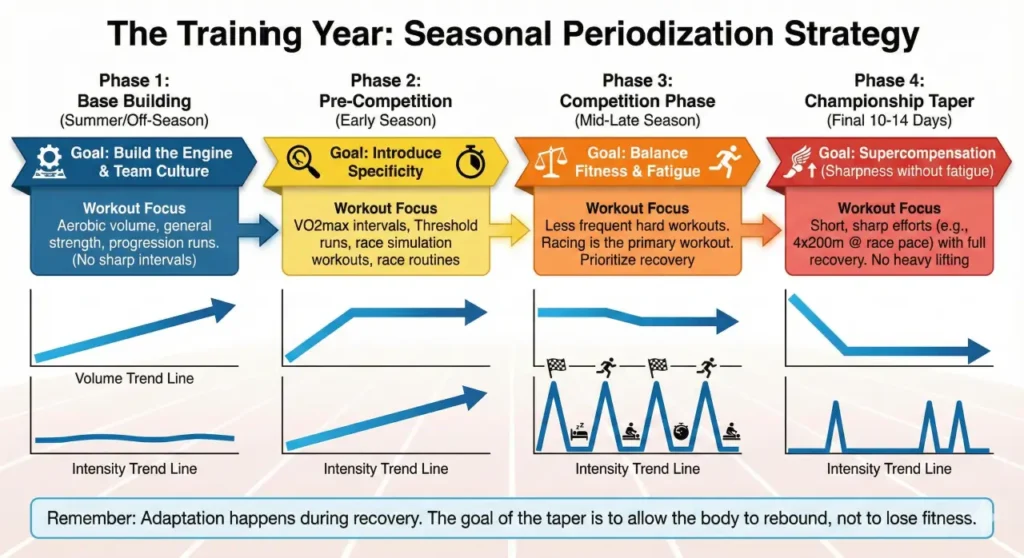

The Training Year: Periodization for High School

High school sports operate on compressed timelines. You might have 14 weeks of cross country followed by 12 weeks of track, with limited off-season development time. Effective periodization—organizing training into purposeful phases—is essential.

Base Building (Summer/Off-Season)

This is your foundation period. Emphasis should be on gradually increasing mileage, developing general strength, and accumulating aerobic volume. Workouts, if included, should be aerobic power efforts—progression runs, longer tempo segments—rather than sharp VO2max intervals.

This is also when you develop the team culture that will carry through the season. Summer training should be engaging enough that athletes want to participate, but not so intense that they arrive at official practice exhausted.

Pre-Competition (Early Season)

As competition approaches, training becomes more specific. Weekly mileage might plateau or slightly decrease while workout intensity increases. VO2max intervals, threshold runs, and race-specific pace work enter the rotation.

Continue strength training 2-3 times weekly. Begin race simulation workouts. Practice race-day routines, including warm-up protocols and pre-race mental preparation.

Competition Phase

This is the balancing act—maintaining fitness while managing fatigue from racing. Weekly mileage often decreases 10-20% from peak volume. Hard workouts occur less frequently, with some weeks containing only one quality session plus the race. A typical late-season race week: Monday/Tuesday easy, a short quality workout Wednesday, Thursday easy, a very easy shakeout run on Friday, and a race Saturday.

Drop volume during competitive phases. Under-rested athletes cannot perform their best, and risk accumulates quickly.

Championship Preparation – The Taper

The 10-14 days before your championship meet require precise management. Reduce volume by 30-50% while maintaining some intensity to preserve neuromuscular sharpness. Include short, sharp efforts—4-6 x 200m at 5K pace with full recovery—to keep legs feeling fast without accumulating fatigue.

Athletes often feel anxious during the taper, worried they’re “losing fitness” from reduced training. Educate them: supercompensation—the body’s performance rebound following training stress reduction—is real. Trust the process.

Common Coaching Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Mistake #1: Training Everyone Identically

Individual differences in maturation, training history, and response to training are enormous. The workout that perfectly challenges one athlete might be too much, or too little, for others.

Solution: Create training groups based on current fitness and training age, not grade level or race times. Assign different paces, distances, or recovery periods within the same workout structure. Accept that individualization requires more planning but produces better outcomes.

Mistake #2: Chronic Moderate Intensity

Don’t get in the habit of telling your athletes they did a good job every day. Runners doing all their easy runs too fast and their hard workouts not hard enough—perpetually stuck in moderate intensity—never develop optimal fitness. They’re too tired to truly push hard workouts but never recovered enough to benefit from easy days.

Solution: Be ruthless about pace discipline. Easy runs should be genuinely easy, often slower than athletes instinctively want. Hard workouts should be appropriately challenging. There should be clear distinction between training intensities.

Mistake #3: Ignoring Non-Running Stressors

Training stress is just one input into an athlete’s total stress load. Academic pressure, part-time jobs, family issues, relationship drama, inadequate sleep—all these affect training capacity.

Solution: Communicate regularly with athletes. When you notice performance declining or mood shifting, investigate before assuming they’re “not trying hard enough.” Sometimes the best coaching decision is reducing training volume to accommodate external stressors.

Mistake #4: Sacrificing Long-Term Development for Short-Term Success

The temptation to overtrain talented freshmen or sophomores, chasing immediate results, is strong. But athletes who peak as sophomores rarely reach their potential by senior year. Worse, some burn out entirely.

Solution: Take the long view. Prioritize consistent, progressive development over multiple years. Accept that sometimes holding back an athlete’s training—even when they beg for more—is the right decision. Your job is developing lifetime runners, not just seasonal success.

Communication: The Art of Coaching

Technical knowledge matters, but coaching is fundamentally about relationships and communication. How you interact with athletes profoundly impacts their development. They won’t remember you for the way you explained a threshold run, but they will remember the way you made them feel supported during the passing of their grandfather. Communication is also a vital part of managing parent relationships.

Feedback That Motivates

Research consistently shows that feedback emphasizing effort, strategy, and improvement outperforms feedback focused on ability or outcomes. “You executed that race plan perfectly, staying patient through two miles before making your move at the crest of the hill like we planned” is more valuable than “Good job winning.”

Provide specific, constructive feedback that helps athletes understand what they did well and what to adjust. Avoid generic praise or criticism. The runner who struggles to a disappointing finish benefits more from “Your first mile was too aggressive given the conditions; let’s discuss pacing strategy” than “That was a tough one. Good job.”

The Power of Autonomy-Supportive Coaching

Involving athletes in decision-making—within appropriate boundaries—increases their investment and intrinsic motivation. This doesn’t mean letting athletes design their own training (you’re the expert), but it means soliciting input and explaining rationale. I do this a lot, often times I’ll do this towards the end of a difficult set of reps. It really speaks to their mindset and informs you as a coach.

“We have two workout options this week: 5x1Ks at threshold, or 6x800m at vVO2max. Given where you are in training, I think option A makes sense, but what are your thoughts?” This approach respects athletes’ autonomy while maintaining your guidance role.

Building Team Culture

Great teams aren’t just collections of fast individuals. They’re groups where athletes genuinely care about each other’s success, where work ethic is contagious, and where struggling runners receive support rather than judgment. It’s about shared goals and family values.

You, the coach, cultivate this through deliberate choices: how you talk about teammates in front of others, whether you celebrate depth as much as top-end talent, how you respond when runners compare themselves negatively to teammates. Model the behavior you want—speak respectfully about all athletes, emphasize team scoring, celebrate personal bests regardless of absolute times.

Working With Different Athlete Types

Not all distance runners are the same. Understanding different athlete profiles helps you coach more effectively. It’s important that you learn how to identify talented young distance runners even before they enter your program.

The Naturally Gifted Runner

This athlete often frustrates their teammates. They make running look easy, often succeed with minimal training, and might resist summer sessions. They’re accustomed to relying on talent rather than work ethic.

Your challenge: help them develop discipline before talent alone stops being sufficient. Emphasize that their current success represents only a fraction of their potential. Show them what serious training could unlock by taking them to events like NXR to see the best in their region.

The Hard Worker with Limited Natural Ability

This runner desperately wants success, trains consistently, and might be tempted to overtrain chasing results they see talented teammates achieve more easily. Coaches love this type of athlete.

Your challenge: help them embrace their own trajectory. Celebrate their improvement, not their placement. Protect them from overtraining by monitoring volume carefully. Help them understand that progress might be slower but is no less valuable. One of my most successful guys wasn’t naturally gifted (only made varsity senior year) but developed the relentless work ethic and mental toughness that made him a 4-year, Division 2 success story after graduation.

The Inconsistent Athlete

Talented but unreliable, this runner trains sporadically, makes excuses, and frustrates you by underperforming their ability. This type can kill a program with their negativity and lack of buy-in.

Your challenge: understand what’s really happening. Sometimes “inconsistency” masks anxiety, depression, or external stressors. Other times it reflects genuine low commitment. Have honest conversations about goals and expectations. If they just don’t care, don’t waste your time on them. But, if there is a way to help them overcome whatever is holding them back, you may have found your 5th runner.

The Anxious Perfectionist

This athlete obsesses over every workout, spirals when things don’t go perfectly, and might develop disordered eating or exercise patterns.

Your challenge: help them develop perspective and self-compassion. Normalize setbacks as part of training. Model healthy attitudes toward food and bodies. Watch for warning signs of overtraining or disordered behaviors, and involve parents and appropriate professionals if concerns arise. This type is often heartbreaking for a coach.

Moving Forward: Your Coaching Philosophy

Effective coaching integrates scientific understanding with practical wisdom, technical expertise with relational intelligence. The research gives us frameworks and principles, but application requires judgment, flexibility, and deep knowledge of the specific athletes in front of you.

My coaching philosophy evolved from “maximum training produces maximum results” to “optimal training produces maximum results, and optimal is highly individualized and contextual.” The athletes who’ve thrived in my program weren’t necessarily the most talented or the ones who trained the hardest. They were athletes whose training matched their needs, whose psychological development paralleled their physical development, and who remained healthy and motivated long enough for consistent work to accumulate into meaningful improvement.

Your program will reflect your own values, knowledge, and context. But regardless of specifics, effective coaching requires:

- Grounding training in exercise science principles while remaining flexible in application

- Treating athletes as developing humans, not just performance machines

- Communicating clearly, compassionately, and consistently

- Taking the long view, prioritizing sustainable development over immediate results

- Continuously learning, adapting, and improving your craft

Note to Coach:

Distance running is beautifully simple in concept—move forward as efficiently as possible for as long as necessary—but endlessly complex in execution. That complexity, that challenge of helping young people discover what they’re capable of, is what makes coaching so rewarding.

Your athletes will remember how you made them feel long after they forget specific workouts or race times. Coach with competence and compassion. Demand excellence while providing support. Challenge athletes while keeping them physically and emotionally healthy.