The Science of Periodization: Building the Perfect High School XC Macrocycle

The season had fallen apart by mid-October.

A talented squad that had looked promising in August was now scattered across the training spectrum—two kids injured, three overtrained and flat, four undertrained and fitness-lagging. The coach, well-intentioned but flying by instinct, had programmed workouts week-to-week based on “feel” without any structure. Hard days piled on hard days. Collegiate workouts that didn’t fit. 10x400s at 1600m pace two days prior to the state meet. Peak fitness arrived in September, six weeks before the championship meet that mattered.

This article is part of our Complete Guide to High School Cross Country Training, which covers everything from seasonal planning to race day tactics.

I’ve seen this movie too many times. And the tragedy? It’s completely preventable.

Periodization—the systematic planning of training into structured cycles with specific physiological goals—is the difference between programs that stumble into occasional success and programs that produce it reliably. Yet many high school coaches either ignore periodization entirely or misapply principles designed for professional athletes to teenagers with 12-week seasons wedged between algebra tests and homecoming dances.

This is the deep dive into how periodization actually works for high school distance running, grounded in the groundbreaking methods of Arthur Lydiard, the research of exercise physiologists like USATF instructor Scott Christensen and the practical insights of coaches like Steve Magness. We’ll explore the physiological evidence for why periodization matters, how to structure macrocycles around the compressed high school calendar, and what mesocycle progressions actually develop the specific adaptations that racing requires.

Because if you’re going to ask kids to run until their legs burn and their lungs scream, you owe them a plan that’s built on more than hope. Anything less isn’t just irresponsible—it is negligence.

The Physiological Case for Periodization

Scott Christensen, a longtime high school coach and exercise science educator, makes the research clear in his extensive writings on training theory: the human body adapts to stress through progressive, specific stimuli applied in the right sequence. Throw random stress at an athlete and you’ll get random adaptations—or worse, conflicting adaptations that cancel each other out.

When you apply a training stress, the body goes through three phases: alarm (fatigue), resistance (adaptation), and either exhaustion (overtraining) or supercompensation (fitness gain). Periodization is simply the art of managing these phases so you’re constantly riding the wave of supercompensation rather than drowning in exhaustion.

Steve Magness, coach and author of The Science of Running, emphasizes that different training intensities create different and sometimes contradictory adaptations. High-volume easy running builds mitochondrial density, increases capillary networks, and enhances fat oxidation—the aerobic engine. Threshold work improves lactate clearance and raises the ceiling on sustainable pace. VO2max intervals increase maximal oxygen uptake and running economy. Sprint work develops neuromuscular power and anaerobic capacity.

Here’s the problem: you can’t maximize all of these simultaneously. If you try to develop everything at once (ex: increase volume and intensity at the same time) and you develop nothing optimally. As Alex Hutchinson notes, the body has limited adaptation resources. High-intensity work and high-volume work both require recovery and create systemic stress. Stack them together without structure and you either underperform or break down.

This is where periodization becomes non-negotiable. By organizing training into sequential phases where specific adaptations are prioritized, you create a cumulative fitness that’s greater than the sum of its parts. Enter Coach Lydiard and his famous training pyramid.

Scott Christensen puts it simply: “Train everything all the time and you’ll be mediocre at everything. Train things in sequence, building each adaptation on the foundation of the last, and you’ll be exceptional when it counts.”

Understanding the High School Macrocycle

A macrocycle is the largest training cycle—typically an entire season or training year. For high school runners, we’re usually working with three distinct macrocycles annually: cross country (August through November), indoor track (December through March in many states), and outdoor track (March through June). Summer serves as an extended base phase bridging cycles.

The critical constraint for high school? Compressed timelines. College and professional runners might spend 16-20 weeks preparing for a championship race. High school cross country? You’ve got 12 weeks from first practice to state meet, often less. Indoor and outdoor track are similarly condensed.

This compression changes everything. You can’t follow a traditional Lydiard-style buildup of 12 weeks base, 6 weeks hill work, 4 weeks speed, and 4 weeks taper. The season would be over before you touched race pace.

The solution, as Magness argues, is concurrent periodization—maintaining multiple training qualities simultaneously but with varying emphasis as the season progresses. You never completely abandon base work, or strides, or speed, or strength, but the ratio of volume to intensity shifts systematically across mesocycles.

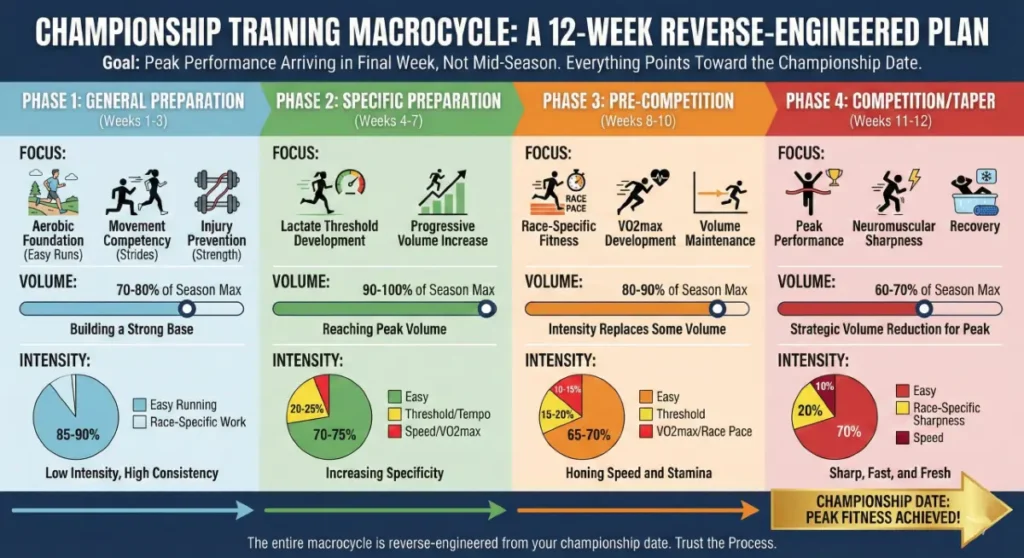

A properly structured high school cross country macrocycle

Phase 1 (Weeks 1-3): General Preparation

- Focus: Aerobic foundation (easy runs), movement competency (strides), injury prevention (strength)

- Volume: 70-80% of season max

- Intensity: 85-90% easy running, minimal race-specific work

Phase 2 (Weeks 4-7): Specific Preparation

- Focus: Lactate threshold development, progressive volume increase

- Volume: 90-100% of season max

- Intensity: 70-75% easy, 20-25% threshold/tempo, 5-10% speed/VO2max

Phase 3 (Weeks 8-10): Pre-Competition

- Focus: Race-specific fitness, VO2max development, volume maintenance

- Volume: 80-90% of season max (intensity replaces some volume)

- Intensity: 65-70% easy, 15-20% threshold, 10-15% VO2max/race pace

Phase 4 (Weeks 11-12): Competition/Taper

- Focus: Peak performance, neuromuscular sharpness, recovery

- Volume: 60-70% of season max

- Intensity: 70% easy, 20% race-specific sharpness, 10% speed

The entire macrocycle is reverse-engineered from your championship date. Everything points toward peak fitness arriving in that final week, not in week 6 when it doesn’t matter.

Common Periodization Failures and Fixes

| FAILURE | SYMPTOM | FIX |

|---|---|---|

| 1. No Plan At All | Workouts chosen spontaneously based on “feel.” | Map the season in July to ensure structure exists before flexibility is applied. |

| 2. The “More Is Better” Trap | Volume and intensity increase simultaneously until burnout. | Inverse Relationship: As intensity rises (Wks 8-12), volume must drop 15-20%. |

| 3. Peaking Too Early | Best races in Sept; flat/injured by Nov. | Patience. September training must look like preparation, not racing. |

| 4. The Plateau Period | Fitness stagnates after week 6. | Variation: Change the emphasis between mesocycles to force new adaptations. |

| 5. Undertapering | Athletes arrive at State Meet tired. | Trust the Taper: Cut volume 30-40% in final 2 weeks; keep intensity high. |

Final Words on the Importance of Periodization

We’ve established the roadmap, but a map is useless if you don’t know how to navigate the terrain. You now understand the what and the why of the macrocycle, yet the championship season is ultimately defined by the daily grind of the how. How do you specifically transition from a volume-heavy General Prep phase to the intensity of Pre-Competition?

The answer lies in the mesocycle—the distinct 3-to-4 week training blocks that act as the concrete stepping stones to your peak. Ready to go deeper? In Part 2, we will cover Building a Championship XC Mesocycle, breaking down exactly how to construct the 3-4 week blocks that turn this theory into daily practice.