Progressive Mileage Guidelines by Age and Experience

I’ll never forget the kid who showed up to practice sophomore year announcing he’d run 60 miles that week because “that’s what David Rudisha (800m world record holder) did when he was my age.” By the of September, he was sidelined with overuse injuries. His fall season? Gone. His ability to help his teammates win a championship in October? Over before the leaves changed.

He wasn’t wrong about wanting to increase his mileage, or even his desire to follow in the footsteps of Rudisha. He was just catastrophically early. That was the first and last time he ignored his coaches’ advice on volume and summer training.

This article is part of our Complete Guide to High School Cross Country Training, which covers everything from seasonal planning to race day tactics.

The Volume Question Nobody Wants to Answer Simply

Every parent asks it: “How much should my kid be running?” Every athlete wants the magic number that unlocks their potential. And here’s the truth that’ll frustrate you—there isn’t one. But there are principles, forged in the foundational work of Arthur Lydiard and refined by Jack Daniels, that can guide us through the minefield of building young distance runners.

Arthur Lydiard revolutionized distance training in the 1960s with a radical idea: aerobic volume builds the foundation for everything else. His New Zealand runners logged massive miles—150-plus weeks—before touching hard speed work. They dominated globally. Daniels later quantified this with his VDOT system, showing us that aerobic development creates the platform for all other training intensities to work.

But here’s what neither coach was primarily dealing with: 14-year-olds juggling algebra homework, growth spurts, and three other sports.

The Factors That Actually Matter

Chronological age is a liar. I’ve coached freshman boys who could pass as 6th graders and freshman boys who looked like they were student teachers at the high school. Biological age—where they actually are in physical development—matters infinitely more than what their birth certificate says. A post-pubescent 15-year-old can handle training loads that would shatter a pre-pubescent 17-year-old who’s a late bloomer.

Training age trumps everything. A veteran sophomore running since middle school is a totally different athlete than the beginner who joined just because their buddy said the pasta parties were fun. The experienced runner has connective tissue that’s been gradually stressed and adapted. The newbie is basically held together with hope and enthusiasm. They need completely different approaches, regardless of their place on the team.

Athlete type shapes the ceiling. Some kids are diesel engines—they grind, they accumulate miles, they get stronger when volume rises. Others are Ferrari engines—brilliant, explosive, but they break if you run them too hard for too long. The diesel-engine kid might thrive on 50 miles a week as a junior; the Ferrari might peak at 35 and fall apart at 40. Neither is better. They’re just different machines requiring different fuel. As a coach you need to be able to identify both types.

Multi-sport athletes need flexibility. That girl playing point guard in winter and lacrosse in spring? She’s getting plenty of general conditioning. Maybe her summer base looks different than the single-sport runner, and that’s not just okay—it might actually save her. I’ve watched too many talented kids choose running over everything else at 14, then burn out by 17 because they lost their joy.

The Lydiard-Daniels Framework for High School

Both Lydiard and Daniels emphasize the same fundamental truth: aerobic capacity is the foundation. Without sufficient easy mileage—running at conversational pace where you’re building mitochondrial density, capillary networks, and cardiac output—you’re building a house of cards.

Daniels talks about running at 65-79% of max heart rate for easy runs, creating the aerobic enzyme adaptations that let you process oxygen efficiently. Lydiard called it “time on your feet” and insisted on months of base building before introducing anaerobic work. The high school application? Most of your miles must be genuinely easy. Forget your Strava ego; if it feels like work, slow down.

Because here’s the secret: volume is what changes you. The long runs on Saturday mornings when you’re half-asleep. The Tuesday shake-out that feels like you’re jogging through molasses. During the accumulated weeks where nothing feels special, your body is quietly becoming a more efficient running machine.

But—and this is crucial—Lydiard was training grown adults with years of base. Daniels himself notes that his VDOT tables and training recommendations assume mature athletes. High schoolers aren’t mature athletes. They’re adults-in-progress. Coaches need to adjust accordingly.

Practical Guidelines by Year and Experience

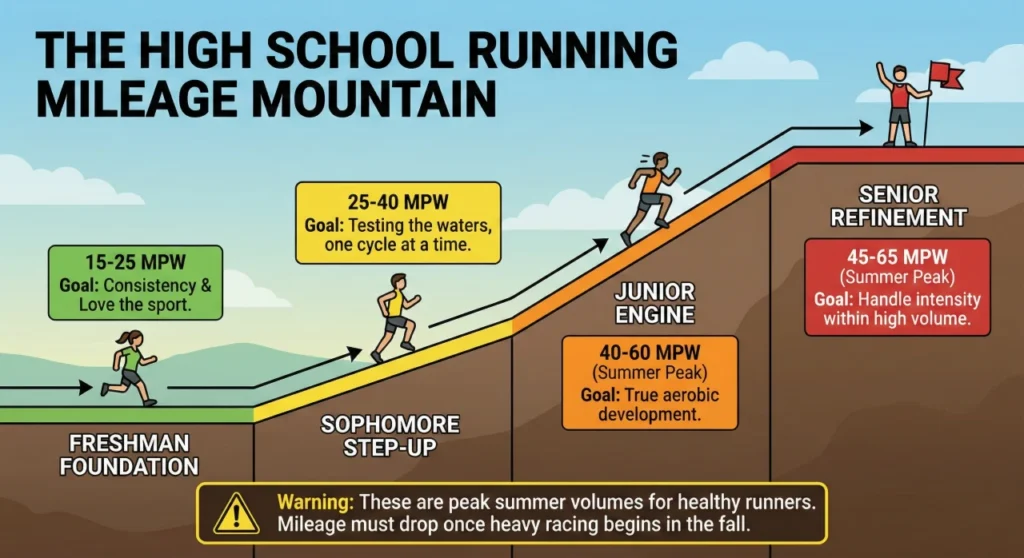

Freshman Year: The Foundation Layer

New runners: 15-25 miles per week maximum. Experienced club runners: 25-30 miles per week.

This is the year you fall in love or fall apart, and volume is almost never why someone falls in love. Focus on showing up, learning what easy pace actually feels like (hint: slower than they think), and running every other day minimum to build consistency.

I had a freshman girl—let’s call her Sidney—who’d never run competitively before. Started at 12 miles a week. By season’s end, she was at 20, smiling at every practice, and ran a 22:30 5K at the JV State Championships. Four years later? College scholarship. Started slow, stayed healthy, built the foundation.

Sophomore Year: Testing the Waters

New runners: 20-30 miles per week. Second-year runners: 30-35 miles per week. Club veterans: 35-40 miles per week.

This is the year for that gradual push. Athletes who built consistency freshman year can now explore what their bodies can handle. The key? One progression cycle at a time. Add miles in summer, hold in fall season. Add again next summer. Don’t spike volume mid-season chasing a PR that’ll cost you the rest of the year.

There was a sophomore named Jake—talented, hungry, super-competitive. He jumped from 30 to 48 miles in three weeks because his teammate was running 50. Tendonitis. Four weeks sidelined. He learned volume is earned, not borrowed.

Crucial Note: These peak mileage numbers are for the SUMMER BASE PHASE. Once racing season starts in September, total volume should decrease as intensity increases.

Junior Year: Building the Engine

Experienced runners: 35-50 miles per week. Elite-level athletes with multiple years: 50-60 miles per week.

Junior year is where Lydiard’s principles really start applying. Juniors with three years of base can handle legitimate volume blocks. This is where we see true aerobic transformation—the kid who was a solid varsity runner becomes a legitimate threat because their engine just got bigger.

But critically: this is still high school. The 60-mile week should be your peak week in summer, not your average week year-round. Daniels warns against chronic high-stress training, and teenagers in school are already under chronic stress.

Senior Year: Refinement and Performance

The experienced senior: 40-55 miles per week, with some elite athletes touching 60-70 at peak summer volume.

By now, you know your body. You know the difference between tired and injured. You’ve earned the right to train at higher volumes because you’ve proven you can handle it. This is where the magic happens—years of accumulated easy mileage coupled with consistent strength training and small, regular doses of speed work.

The Variables That Bend Every Rule

Summer matters exponentially. That 10-week window between seasons? That’s where you build the base that carries the entire year. Can’t do it during season when you’re racing every weekend and doing workouts twice a week. Summer is Lydiard time—long, slow, consistent distance. This is everything for the XC runner. Non-negotiable. Learn more about safe summer base training.

Recovery is training. Daniels quantifies this: quality runs require quality recovery. The 50-mile week with a 12-mile long run and a day of hill repeats needs four or five easy days. Sometimes teenagers skip the easy days because they don’t feel productive. Then they wonder why they’re always tired when the regular season begins.

One breakthrough season. Most high schoolers have one season where everything clicks—volume, health, development, and timing align. Often it’s junior or senior year. This is normal. Not every season will be your best season, and that’s not failure—it’s physiology. Be patient.

“Know when to hold ’em, know when to fold ’em, know when to walk away, and know when to run. -Kenny Rogers

Add mileage when: feel comfortable; no persistent aches; energy levels are good; you’re sleeping well; grades aren’t suffering.

Hold mileage when: racing season starts; growth spurts hit; life stress spikes; school workload intensifies; you’re fighting minor aches.

Back off when: injury whispers start; motivation craters; every run feels like a grind; you’re getting sick frequently; performances decline despite good efforts.

The kid who ran himself into injury sophomore year? He came back junior year. Started at 25 miles weekly. Progressed to 45 by the start of the senior season. Ran a 2:30 in the 1000m as a senior, breaking the existing school record, winning states and continued his successful running career in college. He learned that volume is a long game.

The Unsexy Truth About Building Distance Runners

Lydiard and Daniels both preach patience—months of base before intensity, years of development before peak performance. High school careers are four years, which feels like forever when you’re 14 or 15 but is actually a blip in a running lifetime.

The best high school runners I’ve coached weren’t always the most talented. They were the ones who showed up, progressed slowly, stayed healthy, and trusted the process when it felt boring. They logged thousands of easy miles before the magic happened.

Your freshman year mileage doesn’t determine your senior year success. Your consistency does. Your patience does. Your willingness to build the foundation and do the boring things: core work, strength training, form drills and strides.

Start where you are. Progress gradually. Listen to your body more than your ego. Focus inwardly, don’t measure yourself by someone else’s progression or success. And remember—volume is the tide that lifts all boats, but you’ll miss the wave by launching too early.

The miles will be there. They’ll wait. Build toward them like you’re constructing something meant to last, because the best runners? They’re still running long after the high school finish line fades in the rearview mirror.

Now that you understand the four-year progression, learn how to implement the crucial base phase in How to Build Base Without Getting Injured.