The Chimp Paradox for Runners: Master Your Mental Game

Mile 2 of your 5K race. Your legs are screaming. Your chimp brain is throwing a full-blown tantrum: “Why are we doing this? This is stupid. We should stop. We could just walk. We can just say we are hurt or sick. No one would judge us.”

Sound familiar?

What if I told you that voice isn’t really you—it’s your inner chimp? And more importantly, what if you could learn to manage it?

Dr. Steve Peters’ revolutionary “Chimp Paradox” model has helped Olympic athletes, elite performers, and everyday people understand the battle happening inside their heads. For distance runners, coaches, and parents supporting young athletes, this framework isn’t just interesting psychology—it’s the difference between DNF and PR, between burnout and breakthrough.

Let’s explore how understanding your chimp can transform your running.

Understanding Dr. Steve Peters’ Chimp Paradox Model

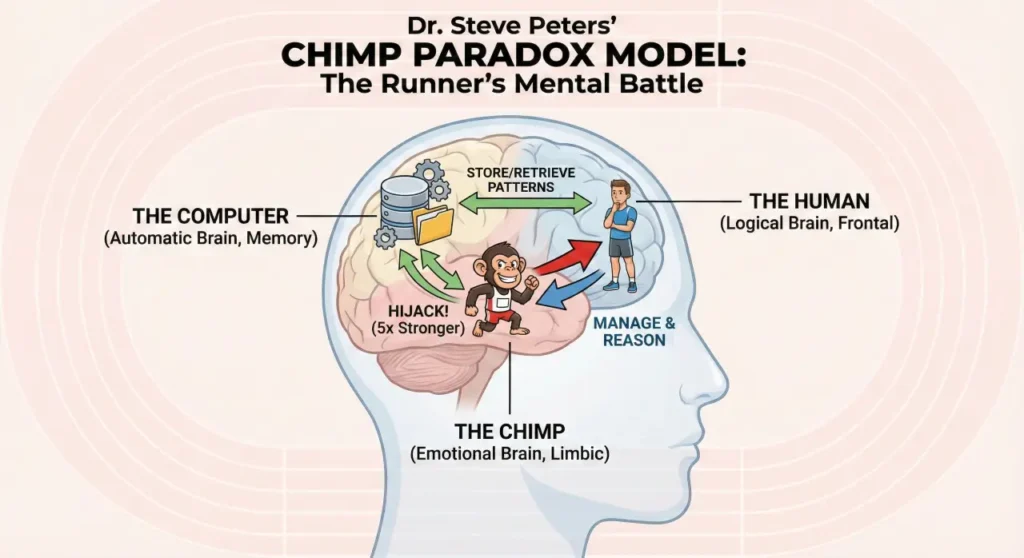

Dr. Steve Peters, a psychiatrist who worked with British Cycling and helped athletes win multiple Olympic gold medals, developed a simple but powerful model for understanding how our minds work. According to Peters, we have three main parts to our psychological makeup:

THE CHIMP – Your emotional, impulsive side that thinks in black and white, catastrophizes, and reacts based on feelings rather than facts. It’s fast, powerful, and often irrational.

THE HUMAN – Your rational, logical side that thinks things through, considers consequences, and makes decisions based on facts and values. It’s slower but more accurate.

THE COMPUTER – Your automatic thinking patterns, habits, and stored beliefs that run on autopilot without conscious thought.

Here’s the critical insight for runners: Your chimp is 5X times stronger than your human. When your chimp gets triggered during a hard workout or race, it can hijack your thinking completely. That’s why even the most logical training plan can fall apart when emotions take over.

The Psychology of Distance Running: Why You Need This Model

Distance running is unique in how it exposes our mental vulnerabilities. Unlike sports with constant external stimulation, running gives us long stretches of time alone with our thoughts. This is great when you’re enjoying a long run to clear your head or want some alone time. But during a hard workout or a race, let’s face it, your chimp has plenty of opportunity to speak up:

- During those brutal 400m repeats when it whispers “you can’t do this”

- At 3:00 AM before race day when it catastrophizes about everything that could go wrong

- When comparing yourself to faster runners on Strava and feeling inadequate

- After a disappointing race when it wants to quit entirely

The physical pain of distance running is real, but it’s often the chimp’s interpretation of that pain that determines whether you push through or fall apart. Here’s a common misconception that drives runners crazy—learning to recognize and manage your chimp isn’t about becoming mentally tougher—it’s about becoming mentally smarter.

The Three Minds in Action: A Runner’s Perspective

Your Chimp Brain on Running

Your chimp operates on survival instinct. When you’re halfway through a tempo run and breathing hard, your chimp interprets this as danger:

Notice the emotional, catastrophic, absolute nature of these thoughts. Your chimp doesn’t deal in nuance. It deals in drama. OMG!

The chimp also hijacks your thinking before runs. “It’s too cold.” “I’m too tired.” “One missed workout won’t matter.” “I think my ankle hurts.” These aren’t rational assessments—they’re your chimp trying to keep you comfortable and safe.

Your Human Brain on Running

Your human, when it can get a word in, thinks differently:

The human reviews facts, recalls past experiences, and makes rational decisions aligned with your actual goals.

Your Computer Brain on Running

Your computer stores all your automatic patterns:

The computer is neutral—it runs whatever programs you’ve installed. The key is recognizing which programs are helpful and which need updating.

The Four Steps to Managing Your Chimp on the Run

Dr. Peters offers a practical framework that distance runners can apply immediately:

1. Recognize Your Chimp

The first step is simply noticing when your chimp is talking.

- During hard efforts when discomfort triggers emotional reactions

- When you’re comparing yourself to others

- Before important races when anxiety builds

- After setbacks when you want to catastrophize

2. Acknowledge the Chimp

Don’t try to suppress or ignore your chimp—that only makes it louder. Instead, acknowledge it: “Okay, I hear you, chimp. You’re scared/uncomfortable/worried.”

For runners: When your chimp screams “I can’t do this!” during a race, you might internally respond: “I hear you, chimp. You’re uncomfortable, and you want this to stop. That’s normal.”

3. Challenge the Chimp with Facts

Once you’ve acknowledged your chimp, bring in your human to examine the actual facts:

- Chimp: “This pace is too hard—I’m going to blow up!”

- Human: “My heart rate is 165, which is exactly where it should be for this effort. I’ve sustained this in training.”

- Chimp: “I’m so much slower than everyone else—I’m terrible at this!”

- Human: “I’m running my race at my current fitness level. Progress isn’t linear, and I’ve improved significantly over the past six months.”

4. Let Your Human Take Control

Once you’ve challenged the chimp with facts, make a conscious decision from your human brain about what to do next. This might mean:

- Staying at the planned pace despite discomfort

- Adjusting the plan based on legitimate data (heart rate, weather, injury warning signs)

- Using a mantra or focus cue to override chimp chatter

- Breaking the race into smaller, manageable segments

Practical Applications for Runners, Coaches, and Parents

For Athletes: Race Day Chimp Management

Pre-race: Your chimp will catastrophize. Expect this. Have your human ready with facts:

- “I’ve trained for this distance and pace”

- “Nerves are normal and don’t predict performance”

- “My taper has prepared me—feeling flat is expected”

During the race: When your chimp panics (and it will), use the four-step process:

- Notice: “My chimp is freaking out about this hill”

- Acknowledge: “You’re uncomfortable, chimp—I get it”

- Challenge: “My splits show I’m on pace, and I’ve trained on tougher hills”

- Decide: “I’m maintaining effort through this hill, then reassessing at the top”

Post-race: Your chimp will either inflate success (“I’m amazing!”) or catastrophize failure (“I’m terrible!”). Let your human do the analysis with facts and perspective.

For Coaches: Teaching Chimp Management

Make it explicit: Introduce the chimp model to your athletes. Give them language to describe their mental challenges.

Create chimp-aware workouts: Design sessions where athletes practice managing their chimp:

- Progressive runs where discomfort builds gradually

- Negative-split workouts that challenge catastrophic thinking

- Time trials that expose chimp voices in race-like conditions

Debrief the mental game: After tough workouts, ask:

- “When did your chimp show up?”

- “What was it saying?”

- “How did you respond?”

- “What would your human have said?”

Model it yourself: Share your own chimp struggles. Normalize the experience and show it’s manageable.

For Parents: Supporting Young Runners

Normalize the chimp: Help your young athlete understand that everyone has a chimp, even Olympic champions. It’s not a weakness—it’s biology.

Don’t fuel the chimp: When your athlete is catastrophizing before a race (“I’m going to finish last!”), resist the urge to over-reassure or dismiss. Instead, ask: “Is that your chimp talking? What would your human say?”

Celebrate mental management: Praise effort in managing emotions, not just race results. “I noticed you stayed calm when things got tough in that race—that’s huge growth.”

Watch your own chimp: Your anxiety can trigger your athlete’s chimp. Before competitions, manage your own nervous energy so you’re not amplifying their stress.

Create psychological safety: Make sure your athlete knows that struggling mentally doesn’t mean they’re weak, and that they can talk to you about chimp challenges without judgment.

Take Action: Start Managing Your Chimp Today

This week: During your next hard workout or race, simply notice your chimp. Don’t try to change anything yet—just observe. What does your chimp say when things get uncomfortable? Write it down afterward.

This month: Practice the four-step process (Recognize, Acknowledge, Challenge, Decide) during increasingly difficult running situations.

This season: Track your mental management progress alongside your physical training. Celebrate the moments when you successfully navigated a chimp hijacking.

Want to go deeper? Read Dr. Steve Peters’ book “The Chimp Paradox” for the complete model and additional strategies. Consider working with a sports psychologist who can help you apply these concepts to your specific mental challenges.

Remember: every elite runner has a chimp. The difference between good and great often comes down to who’s in charge when the going gets tough.