Zone 2 Training for High School Runners: Solving the 4-Year Burnout Crisis

It was mid October, more than halfway through cross country season and a week before Divisionals, and I was chatting with another coach after practice when Sarah’s mom called my cell.

“Coach, can we talk?”

Sarah was one of my varsity girls—a junior with legitimate talent. She’d been a standout freshman, improved her sophomore year, and was supposed to have a breakout season. Instead, she’d been struggling. Not injured, exactly. Just… off. Quiet. Head down during races.

“She doesn’t want to run anymore,” her mom said quietly. “She’s exhausted all the time. She says practice feels like a chore. We thought maybe she was anemic, but the blood work came back fine. I think she gets along with the other girls. I know she likes you. I don’t know what’s wrong.”

I’d seen this movie before. Too many times, actually.

Sarah wasn’t sick. She wasn’t overtrained in the traditional sense—we’d been careful about mileage progression and recovery weeks. But somewhere between her freshman enthusiasm and junior year reality, running had stopped being something she wanted to do and started becoming something she had get through.

She was burned out. And she was only 16.

The brutal truth? Coaches do this to kids all the time. We take talented freshmen, push them hard because they can handle it, watch them improve for two years, and then wonder why they’re zombies by senior year—if they even make it that far.

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, 70% of youth athletes quit organized sports by age 13. The ones who make it to high school? Many are running on fumes by their final season.

And here’s what really keeps me up at night: we’re doing it wrong from the very beginning. We need to rethink our approach in terms of “career,” not “season.” This where Zone 2 training for high school runners comes in.

⏱️ The “Too Long; Didn’t Read” Summary

We are “coaching the fun out” of distance running. High-intensity training is causing a burnout epidemic, leaving talented athletes as physical and mental “zombies.”

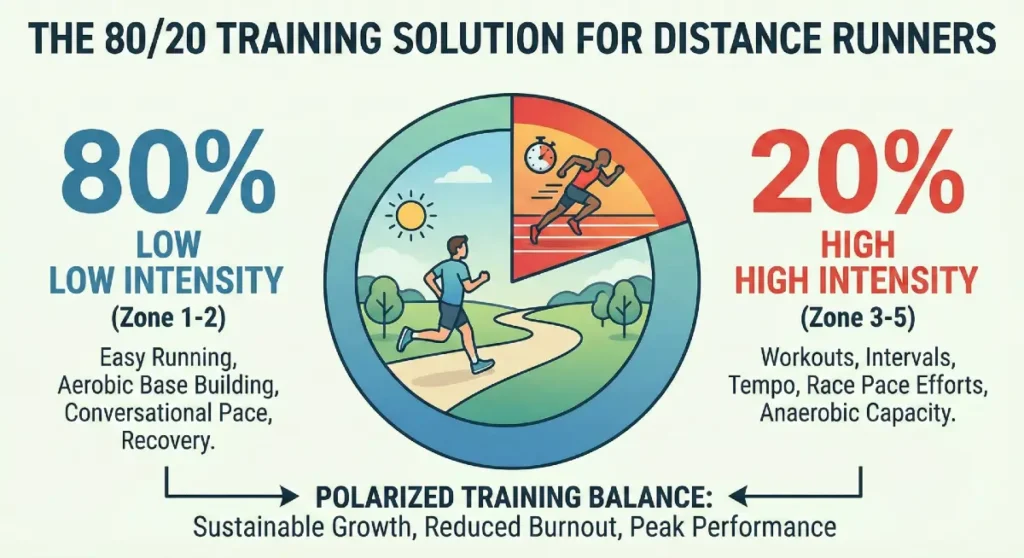

Adopt the 80/20 principle: 80% of weekly volume at a conversational Zone 2 intensity (aerobic) and 20% at high intensity.

Zone 2 triggers mitochondrial biogenesis and increased capillary density—building the aerobic engine required for elite racing without the “crash.”

The Demographic Divide in Athlete Retention

| Demographic Group | Participation (Ages 6-17) | Primary Reason for Quitting |

| All Youth | ~54% | “Not having fun anymore” |

| Girls (Varsity) | ~48% | High perceived pressure / Burnout |

| Boys (Varsity) | ~56% | Injury / Specialization fatigue |

| Black/African American | ~42% | Lack of access/Cost (at younger ages) |

| Hispanic/Latino | ~38% | Community infrastructure |

The Longevity Crisis Nobody Talks About

Let’s be honest—when we talk about “athlete development” in high school distance running, what we really mean is: “How do I get this kid to run a faster 5K this season?”

Next season? That’s future Coach’s problem.

Four-year development plan? That’s all well and good and we have the best intentions. But, most programs are just trying to survive the next invitational.

But here’s the thing that’s been creeping into mainstream fitness culture over the past year and completely changing how smart coaches think about training: longevity and metabolic health.

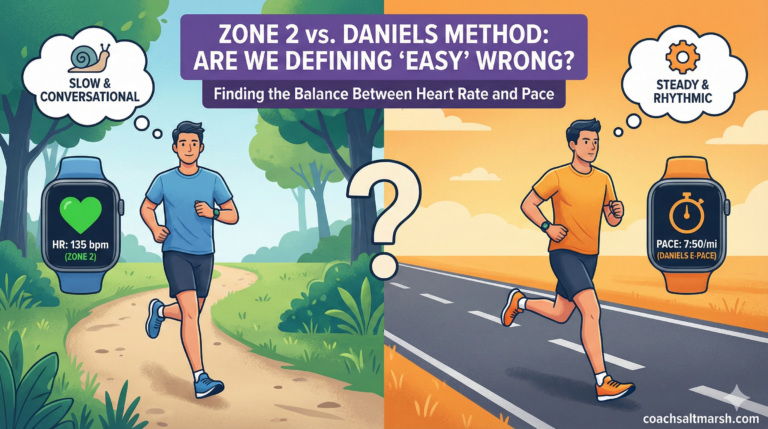

In 2026, “Zone 2 training” has moved from the realm of endurance nerds and biohackers into the general consciousness. The 80/20 principle—80% of weekly training volume at low intensity (Zone 2), with only 20% at high intensity has taken hold. I first encountered this concept when Matt Fitzgerald provided me with an advance copy of his book, 80/20 Running.

The longevity crowd is obsessed with mitochondrial health. Even your aunt who does Pilates twice a week is talking about her VO2 max. And you know what? They’re onto something that distance coaches should have been prioritizing all along.

Because when you dig into the science of what actually builds durable, long-term athletic performance, it’s not the sexy interval workouts or the crushing tempo runs.

It’s the slow, boring aerobic work that nobody wants to do.

What the HeCK is Zone 2, Anyway?

Before we go further, let me define this clearly because there’s a lot of confusion out there.

Zone 2 training is exercise at an intensity where your body primarily uses fat for fuel through aerobic metabolism, typically 60-70% of maximum heart rate. This is the effort level just below your first lactate threshold—the point where your breathing gets noticeably harder.

Here’s the practical test: Can you hold a conversation?

Not give one-word answers between gasps. Not manage a sentence every 30 seconds. Actually talk in complete paragraphs without your breathing pattern changing dramatically.

If yes, you’re probably in Zone 2.

If you’re breathing through your mouth, if you can feel lactate building in your legs, if you’d struggle to sing the Brady Bunch theme without pausing—you’re above Zone 2.

For many high school runners, Zone 2 pace is painfully slow. Like, “I could walk faster than this” slow for some kids. Which is exactly why they don’t want to do it.

Your freshmen boys will complain. Your competitive juniors will feel like they’re wasting their time. Your parents will wonder if you know what you’re doing.

But here’s what’s happening inside their bodies during those “easy” runs that makes all the difference.

The Science of the “Aerobic Engine”

Inside every muscle cell in your body are these tiny structures called mitochondria. You probably learned about them in 9th grade biology—they’re the “powerhouses of the cell.”

What your biology teacher probably didn’t tell you is that mitochondria are the difference between a XC kid who plateaus sophomore year and one who’s still improving as a senior.

Here’s what research shows happens when athletes do consistent Zone 2 training:

The Biological Payoff: What Happens Inside the Cell

Consistent Zone 2 training isn’t just “easy running”; it’s a high-level physiological renovation. Here is how your athletes’ bodies transform from the inside out:

1. Mitochondrial Biogenesis (Building the Fleet)

Zone 2 work stimulates the creation of brand-new mitochondria and increases mitochondrial density. This allows cells to generate energy far more effectively.

The Analogy: Think of it like adding more engines to a car. You want to race faster? Don’t just tune the single engine you have—build thousands of new ones. More mitochondria = more energy production capacity.

2. Metabolic Flexibility (The Hybrid Advantage)

This is the ability to efficiently switch between burning carbohydrates and fats for fuel. Athletes with high metabolic flexibility maintain energy without lactate accumulation.

- Better Blood Sugar Regulation: Improves insulin sensitivity.

- Late-Race Power: Kids don’t “bonk” as hard when glycogen stores get low.

- Faster Recovery: Efficient fuel switching speeds up the cellular cleanup process.

The Analogy: It’s like a hybrid automobile. You aren’t just reliant on the limited “gas” (glycogen); you’ve unlocked a massive, sustainable “battery” (fat oxidation).

3. Capillary Density (The Delivery Network)

Zone 2 training increases the number of tiny blood vessels (capillaries) that deliver oxygen directly to the muscle fibers.

- Better Oxygen Delivery: More pipes mean more oxygen reaches the “engines.”

- Waste Removal: Faster clearance of metabolic byproducts during hard efforts.

- The Bottom Line: Better blood flow = better performance. It’s that simple.

Capillary density is your body’s “Amazon Prime” delivery service. It ensures that oxygen arrives exactly when needed and that the “metabolic trash” is hauled away before it causes a bottleneck. You don’t win races by having the loudest factory; you win by having the best supply chain.

4. Fat Oxidation Capacity (Expanding the Tank)

At lower intensities, the body preferentially burns fat for fuel. Training this system increases the “time to fatigue” and promotes faster muscle tissue recovery.

Build a bigger aerobic engine, and everything else becomes easier.

The Big Picture: When you build a bigger aerobic engine, every other type of training (intervals, tempos, hill repeats) becomes more effective. You aren’t just training for the next race; you’re building a durable athlete.

The Catch: These Adaptations Take Time

You can’t speed-hack mitochondrial development.

Research on endurance athletes shows that these adaptations take time to develop—the amount and intensity of training is crucial to the quantity and quality of mitochondria, and muscle mitochondria have a half-life of only one or two weeks, meaning athletes need consistent aerobic work to maintain these gains.

You want to know why the seniors are burned out? Because they spent three years hammering their glycolytic systems with interval workouts while neglecting the aerobic foundation that takes years to build properly.

It’s like trying to build a skyscraper by starting on the 40th floor. Sure, you might get some impressive-looking architecture up there for a while. But without a solid foundation, the whole thing eventually collapses.

The Senior Year Burnout Syndrome

Let me paint you a picture of how this typically goes wrong:

Freshman Year: Athlete shows up with natural talent. You’re excited. You throw them into workouts with the varsity group because “they can handle it.” And they can—for a while. They PR multiple times. Parents are thrilled. Kid loves running.

Sophomore Year: More of the same. Bump up the mileage. Add another hard workout per week. He’s still improving, though maybe not as dramatically. Some nagging injuries pop up. Nothing serious. You manage it.

Junior Year: Things start getting weird. The PRs aren’t coming as easily. He seems tired more often. You attribute it to harder classes, maybe a demanding social life. You keep the training load high because, hey, this is the year that matters for recruiting.

Senior Year: Your senior runner, and team leader, either (a) limps through the season as a shell of their former self, or (b) quits entirely before the season even starts.

Have you ever seen this happen?

This is the predictable result of what exercise scientists call “overtraining syndrome”—extended periods where training loads exceed recovery capacity, resulting in decreased performance, increased injury and illness risk, and derangement of endocrine, neurologic, cardiovascular, and psychological systems.

But here’s what’s interesting: the problem usually isn’t too much volume. It’s too much intensity for too long.

The 80/20 Solution

Elite endurance athletes have known this forever. Stephen Seiler’s research on world-class rowers and cross-country skiers found that successful athletes did approximately 80% of their training at low intensity and 20% at high intensity.

Think about that. The best endurance athletes in the world—people whose literal job is to run/ski/row fast—spend 80% of their training time going slow.

Why? Because that’s what builds the aerobic engine. That’s what creates mitochondrial density. That’s what develops capillary networks and metabolic flexibility.

The hard stuff? That’s just teaching your body to access the engine you’ve built.

But most high school programs flip this ratio. We do maybe 50-60% easy running and 40-50% hard work. Some programs are even worse—closer to 70/30 in the wrong direction.

And then we wonder why kids are cooked by their senior year.

What This Actually Looks Like in Practice

Okay, enough theory. Let’s talk about what implementing an 80/20 approach actually means for your program.

For Freshmen and Sophomores:

Your job in years 1-2 is to build the biggest aerobic engine possible.

- 80-85% of weekly volume at conversational pace

- One workout per week maximum (and often just strides or hill repeats, not full intervals)

- Focus on gradually increasing weekly mileage (following the 10% rule)

- Teach good form and running mechanics

- Make running fun and social

I know what you’re thinking: “But Coach, if I don’t have them doing 800m repeats, they won’t get faster!”

Wrong. They’ll get faster from the sheer volume of aerobic work. Research shows that for developing athletes aerobic work is more valuable than occasional crushing workouts. Your freshman who runs 40 miles a week at easy pace will improve more than the freshman who runs 30 miles with two hard workouts.

For Juniors:

This is where you start adding intensity, but still protecting the base.

- 75-80% of weekly volume easy

- Two moderate workouts per week (tempo runs, cruise intervals, fartleks)

- Strategic hard efforts before key races

- Continue building mileage ceiling

- Emphasize race-specific fitness

Notice we’re still at 75-80% easy work. This is a competitive junior who’s ready to race hard and chase PRs. And we’re STILL protecting that aerobic foundation.

For Seniors:

The victory lap—harvest what you’ve planted.

- 70-75% easy (the lowest percentage, but still the majority)

- Two hard workouts per week

- Peak training load (but not increased training load)

- Race frequently and aggressively

- Trust the fitness is there

By senior year, if you’ve done this right, you have an athlete with:

- Massive mitochondrial density built over three years

- Elite fat oxidation capacity

- Excellent metabolic flexibility

- Strong aerobic foundation that can support high-intensity work

- Fresh legs and genuine enthusiasm for the sport

Instead of a burned-out shell of a kid who just wants the season to be over.

But Won’t They Be Slow If They Train Slow?

This is the #1 pushback I get from coaches, athletes, and parents.

“If we’re running 8:00 pace on easy days, how will they learn to race 5:30 pace?”

Two answers:

Answer #1: The hard workouts teach race pace. That’s what the 20% is for. When you show up to your interval session fresh—because you didn’t trash yourself on yesterday’s “easy” run—you can actually hit the prescribed paces and get the intended training stimulus.

Answer #2: The aerobic system is the limiting factor for almost all high school distance runners.

Let me say that again because it’s important: For 95% of high school kids, their ceiling is determined by their aerobic capacity, not their speed.

Your 18:00 5K runner isn’t running 18:00 because they lack speed. They’re running 18:00 because their aerobic engine can’t sustain a faster pace for 3.1 miles. Heck, they can probably hammer an 800 at 4:30 pace. It’s not a speed problem.

Build a bigger engine (Zone 2 work) and the speed takes care of itself.

The Controversy: Does Zone 2 Even Matter?

Now, I need to address something that came out recently and is causing some confusion in coaching circles.

A 2025 research review concluded that current evidence does not support Zone 2 training as uniquely optimal for mitochondrial adaptations, and that higher-intensity exercise may produce superior adaptations from a biochemical perspective.

Some coaches saw this headline and thought: “See! Zone 2 is overrated! Let’s go back to crushing our kids!”

But here’s what they’re missing:

The study doesn’t say Zone 2 doesn’t work. It says that higher intensity ALSO works for mitochondrial adaptations—and might even work better in isolation.

The key phrase is “in isolation.”

Because here’s the reality: You can’t do high-intensity work 7 days a week. Your body will break down. The research acknowledges this: Zone 2 depletes little glycogen and requires minimal recovery time, allowing athletes to continue exercising on days when they can’t sustain higher intensities.

So yes, a hard interval session might trigger more mitochondrial biogenesis than an easy run. But you can’t do intervals every day. You CAN do Zone 2 work almost daily. And the cumulative effect of consistent aerobic work over months and years is what builds championship athletes.

The Metabolic Health Angle

Here’s where this gets really interesting and why the longevity crowd is so obsessed with Zone 2 work.

Recent research shows Zone 2 training has profound effects on overall metabolic health:

- Enhances metabolic flexibility by increasing fat burning and improving insulin sensitivity

- Reduces risk of diabetes, obesity-related complications, and cardiovascular disease

- Supports cellular resilience, long-term cardiovascular health, and parasympathetic tone

- Can be performed daily with easy recovery, making it ideal for building sustainable exercise habits

In other words: Zone 2 training doesn’t just make better runners. It makes healthier humans– for life!

And isn’t that supposed to be the point of high school athletics? Not just winning cross country meets, but helping kids develop habits and capacities that will serve them for life?

When I prioritize Zone 2 work with my freshmen and sophomores, I’m not just building better runners. I’m teaching 14-year-olds that slow, consistent work builds real fitness. That you don’t need to destroy yourself every workout. That sustainable effort over time beats sporadic heroics.

These are lessons that apply to everything: academics, relationships, career, health.

A Real Conversation I Had with a Parent

Parent: “Coach, I don’t understand why Bekah is running so slow on her easy days. Don’t we want her to get faster?”

Me: “Absolutely. That’s exactly why she’s running slow.”

Parent: “But… that doesn’t make sense.”

Me: “Okay, think about it this way. Bekah’s muscles need more mitochondria—that’s what produces energy aerobically. Zone 2 work is the most efficient way to trigger mitochondrial growth. If she’s running too hard on easy days, she’s training her glycolytic system, which is already well-developed. She’s also accumulating fatigue that will make her hard workouts less effective. Running easy allows her to accumulate more total volume, triggers the specific adaptations she needs, and keeps her fresh for quality sessions. Make sense?”

Parent: [silence]

Me: “Here’s what I’m asking you to trust: By the time Bekah is a senior, if we do this right, she’ll have an aerobic engine that will support whatever goals she has. She’ll still love running. And she’ll have learned habits that will keep her fit for life. That’s worth more than shaving 20 seconds off her 5K time as a freshman by running her into the ground.”

Most parents get it once you frame it this way. Some don’t. That’s okay—you’re the coach, not them.

The Four-Year Blueprint

So what does a proper 4-year development plan actually look like? Here’s my framework:

Year 1: Freshman

Primary Goal

Establish consistent training, learn good form, and build a massive aerobic base.

Year 2: Sophomore

Primary Goal

Continue base building and introduce structured, race-specific workouts.

Year 3: Junior

Primary Goal

Peak performance for recruiting and developing high-level mental toughness.

Year 4: Senior

Primary Goal

Deliver best career performances and leave a legacy on the course.

Common Mistakes Coaches Make

After 25 years of doing this, I’ve seen every possible way to screw up athlete development. Here are the big ones:

Mistake #1: Treating every workout like a race If every practice is a puke fest, when do athletes actually get better? Adaptation happens during recovery, not during the workout itself.

Mistake #2: Comparing athletes to their peers instead of their potential Just because Jon can handle 60 miles a week as a freshman doesn’t mean Henry should do the same. Individual progression matters more than team averages.

Mistake #3: Sacrificing sophomore year for freshman glory The kid who runs 17:30 as a freshman and 17:45 as a senior—that’s a failure of coaching, not a failure of the athlete.

Mistake #4: Ignoring the psychological toll Overtraining syndrome isn’t just physical. The research is clear: significant predictors of burnout include negative affect and worry, with athletes experiencing illness and injury more likely to negatively perceive their performance.

Mistake #5: Not communicating the plan Athletes and parents need to understand WHY you’re having them run slow. Otherwise they think you don’t know what you’re doing (or worse, they go home and train in secret)!

My Challenge to You

If you’re a coach reading this, here is your 5-step action plan.

Audit your current training

Go through the last month of workouts and calculate what percentage of total training volume was at Zone 1-2 intensity vs. Zone 3-5. Be honest.

Have the conversation with your team

Explain what Zone 2 is, why it matters, and how you’re going to prioritize it going forward. Show them the research. Make them understand that running slow is not being lazy—it’s being smart.

Start with your freshmen and sophomores

Don’t try to overhaul your entire program overnight. Start with your youngest athletes—the ones who have the most to gain from a proper aerobic foundation.

Track and communicate progress

This is key: If you’re going to ask kids to trust a process that feels counterintuitive, you need to show them it’s working. Track workout paces, race times, and how athletes feel. Celebrate improvements. Make the invisible visible.

Be patient

Real mitochondrial development takes months and years, not weeks. Trust the process even when results aren’t immediately obvious.

The Bottom Line

Listen, I get it. It’s tempting to push talented freshmen hard because they can handle it. It’s exciting to see immediate results. It feels like good coaching when your kids are running fast workouts.

But if you want athletes who are still improving—and still enjoying running—as seniors, you have to play the long game.

You have to build the aerobic engine first. You have to protect that foundation even when it feels slow and boring. You have to trust that the work you’re doing today is creating the athlete you’ll see in three years.

Because here’s the truth that nobody wants to hear: The most important thing you can give a high school athlete isn’t a fast 5K time. It’s a healthy relationship with the sport that lasts beyond high school.

Zone 2 training does both. It builds the physiological foundation for long-term performance. And it creates sustainable training habits that don’t leave kids broken and burned out.

That kid who’s still running in college? Still running in their 30s? Still using fitness as a tool for health and stress management at 50?

That kid learned to value the slow, boring aerobic work. They learned that sustainable beats spectacular. They learned to build an engine that lasts.

And that’s the real longevity we should be coaching toward.

Today, Sarah is a junior in college, still running, and currently training for her first marathon.

🏃♂️ FAQ: Zone 2 RUNNING

The coaching world has been buzzing about recent studies questioning the “uniqueness” of Zone 2. Here is the direct breakdown of what the science actually means for your program.

Is Zone 2 training still necessary after the 2025 research review on HIIT?

Yes. While the 2025 review noted that high-intensity exercise can produce superior mitochondrial adaptations from a strictly biochemical perspective, it does not invalidate Zone 2.

The study looked at these adaptations in isolation. In a real-world training cycle, Zone 2 remains the essential “filler” that allows for high training volume without the systemic fatigue or injury risk associated with daily high-intensity work.

If high-intensity work builds more mitochondria, why not do it every day?

Because of recovery biology. High-intensity sessions (Zones 4 and 5) heavily deplete glycogen and place significant stress on the central nervous system.

If you “crush” your athletes with high intensity every day, their mitochondrial gains will be erased by Overtraining Syndrome (OTS) and injury before the season ends.

Why is the “Low and Slow” approach better for high schoolers specifically?

High school athletes aren’t professionals; they have “hidden” stressors that impact their physiological “budget”:

- Physical Development: Their bones and tendons are still maturing.

- Psychological Load: SATs, social dynamics, and 7:00 AM school starts.

- Lack of Recovery Tech: Most 16-year-olds don’t have access to daily massage, cryotherapy, or 10 hours of undisturbed sleep.

For a teenager, Zone 2 is a safety net. It builds the engine while leaving them enough energy to actually be a student.

Does the 80/20 rule apply if my runners are “low mileage”?

Actually, it’s even more important. Coaches of low-mileage programs often feel they need to make every mile “count” by running them hard. This is a mistake.

Even at 20 miles per week, maintaining the 80/20 ratio ensures that the athlete develops the metabolic flexibility needed to transition to higher mileage in college or their senior year.

- 80/20 Running by Matt Fitzgerald – The definitive book on polarized training

- AAP Guidelines on Youth Overtraining – Medical perspective on preventing burnout

- Mitochondrial Adaptations to Exercise (PMC) – Deep dive into the science