Canova Alternations: A High School XC Workout for the Middle Mile

We have all seen it at track practice. The whistle blows, the athletes hammer a 400m repeat, and then… they stop. Hands on knees, walking in circles, waiting for the heart rate to drop so they can do it again.

This is fine if you are training for the 100m dash. But for the 5k cross country runner, this “stop-and-go” mentality creates a physiological gap. It teaches the body to run fast only when it is fully recovered.

The problem? In the second mile of a cross country race at Derryfield Park or Mines Falls, you don’t get a standing recovery. You have to keep moving.

To fix this, we need to look at the training philosophy of Renato Canova.

Canova is an Italian coaching legend responsible for some of the fastest marathoners and distance runners in history. While his schedules for elites are impossibly high-volume, his core principle of “Specific Endurance” is exactly what high school runners are missing.

Today, we are going to fix your team’s “lactate shuttle” with a workout I call Canova Alternations.

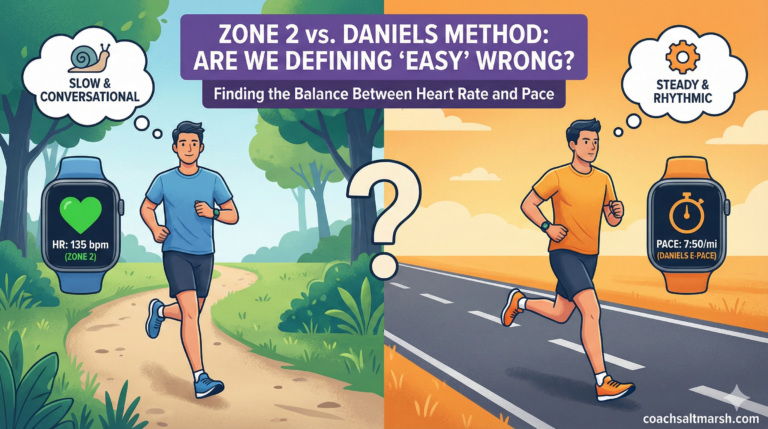

The Science: The “Float” vs. The “Jog”

When your athletes run 5k pace, their muscles flood with lactate. Traditional interval training (Run Hard / Rest Easy) teaches the body to clear that lactate while standing still or jogging slowly.

Canova argues that to race well, you must teach the body to recover while running fast.

We do this by replacing the “jog” recovery with a “float.”

A float is a steady, moderate pace—roughly 45-60 seconds per mile slower than 5k pace. It is fast enough that the body cannot simply flush out waste products passively; it has to actively pump lactate out of the legs to be used as fuel.

It’s the difference between bailing water out of a boat after the rain stops, versus bailing it out during the storm.

The Workout: High School Specific Alternations

Pacing Guidelines for 17:30 and 20:00 Runners

The hardest part of this workout is getting the “Float” right. If they run the “Hard” section too fast, they will be forced to walk the “Float.” That is a failed workout.

We want to control the effort. Here is how I break it down for a Varsity squad:

| Group | Goal 5k | 3 min “ON” Pace | 2 min “FLOAT” Pace |

| Varsity Boy | 17:30 | 5:38/mi (approx. 84s / 400m) | 6:37/mi (approx. 100s / 400m) |

| Varsity Girl | 20:00 | 6:26/mi (approx. 96s / 400m) | 7:34/mi (approx. 112s / 400m) |

Use the Canova Pace Calculator to find your athletes 5K Race Pace (100%) and Steady State (85%) pace.

Coaching Cues: What to Watch For

- “Don’t Fall Asleep on the Float!”

- Teenagers love to treat the recovery as a vacation. You have to be vocal. Remind them that the float is where the fitness is gained. If they look too comfortable during the 2 minutes, they are going too slow.

- Mechanics Under Fatigue

- Watch their form during the 3rd and 4th repetition. Are their hips sinking? Are they over-striding? Canova’s athletes look smooth even when they are redlining. Cue your runners to “stay tall” during the float.

- The “Crash” Safety Valve

- If an athlete is dying and can’t hold the float, slow down the “ON” segment, not the float. It is better to run the hard sections at 95% effort and maintain the steady recovery than to sprint and walk.

Why This Works for High Schoolers

Most high school races are lost in the middle mile. That is where the adrenaline wears off and the lactate builds up.

By practicing these alternations, you are giving your athletes the physical tool to handle that burning sensation without slowing down. You are teaching them that “recovery” doesn’t mean stopping—it just means finding a sustainable rhythm.

Give this a shot during your mid-season phase, perhaps 4-5 weeks out from the State Meet. It’s a grinder, but it builds the kind of engine that doesn’t quit.