Mesocycles: The Engine of Adaptation

Mesocycles are 3-4 week training blocks within the macrocycle, each with a specific physiological target. This is where the magic happens—where abstract periodization theory becomes concrete workouts that create measurable adaptation. This is what you came for, right?

This article is part of our Complete Guide to High School Cross Country Training, which covers everything from seasonal planning to race day tactics.

First, let’s examine each mesocycle phase in detail:

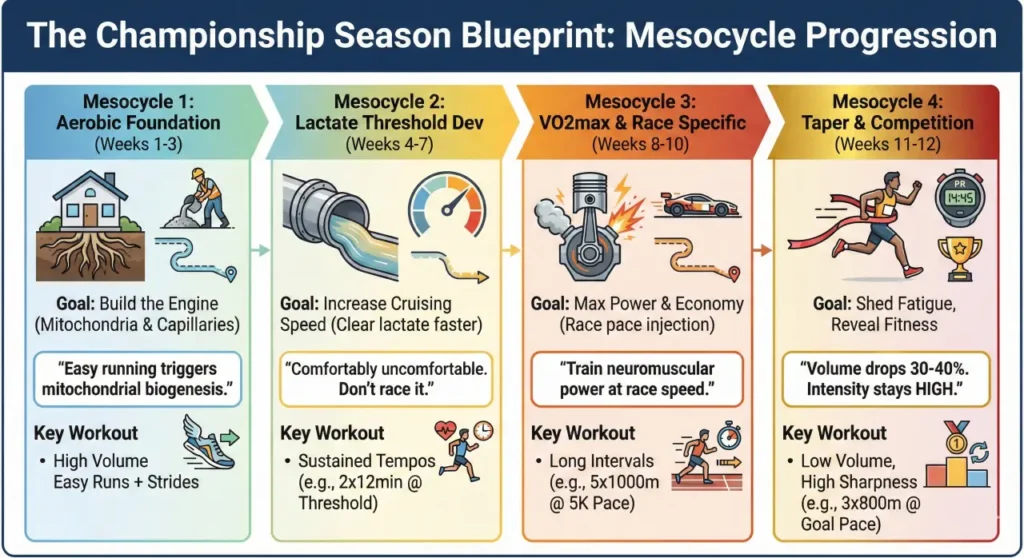

Mesocycle 1: Aerobic Foundation (Weeks 1-3)

Physiological Goal: Increase mitochondrial density, expand capillary networks, develop fat oxidation efficiency, establish movement patterns, build connective tissue resilience.

The Science: Steve Magness points to research showing that easy running at 65-75% max heart rate triggers mitochondrial biogenesis—literally creating new cellular power plants. But this process requires sustained, repeated training. One long run won’t do it. Three weeks of consistent aerobic volume will.

Beginning a season with high-intensity work before establishing aerobic base is like trying to build the second floor of a house before pouring the foundation. The structure might stand briefly but collapses under pressure. Mid-season plateaus await.

What This Looks Like in Practice:

A typical week in mesocycle 1 for an experienced varsity high school runner:

- Monday: 6 miles easy + drills and strides

- Tuesday: 8 miles easy with middle 4 miles progressive (still comfortable)

- Wednesday: 5 miles recovery + core work

- Thursday: 7 miles steady with 6x100m strides

- Friday: 4 miles easy

- Saturday: 10-12 mile long run

- Sunday: Off or 3-4 miles very easy

Total: 40-45 miles, 90% easy aerobic intensity

The long run is the centerpiece—progressively building from 10 to 12-14 miles across these weeks. Strides (15-20 second accelerations at mile race pace) maintain neuromuscular coordination without creating systemic fatigue. Strides should be done with a walk back. Do not rush this process. Pay attention to form and run fast without struggling.

Real World Example: Great Oak High School in California, perennial national contenders, famously builds the first three weeks almost entirely on steady volume. Their July and early August look boring on paper—LOTS of EASY miles, minimal intensity. But by September, when competitors are already tired, Great Oak runners have aerobic engines that keep delivering oxygen efficiently deep into races.

Real World Example: Great Oak High School in California, perennial national contenders, famously builds the first three weeks almost entirely on steady volume. Their July and early August look boring on paper—LOTS of EASY miles, minimal intensity. But by September, when competitors are already tired, Great Oak runners have aerobic engines that keep delivering oxygen efficiently deep into races.

Mesocycle 2: Lactate Threshold Development (Weeks 4-7)

Physiological Goal: Increase the pace at which lactate production exceeds clearance, improve buffering capacity, develop mental comfort with sustained effort.

The Science: Threshold training—running at 85-90% max heart rate, conversational but uncomfortable—creates specific adaptations that pure easy running doesn’t. As Christensen explains, threshold work increases the density of lactate transporters, which shuttle lactate out of working muscles. It also raises the concentration of mitochondrial enzymes that can use that lactate as fuel.

This matters because lactate accumulation is a primary limiter in races lasting 15-25 minutes (exactly the high school 5K range). The faster you can run before lactate floods your system, the faster your race pace.

Magness emphasizes that threshold development requires sustained exposure at the target intensity. A 20-minute tempo run creates adaptation. Six random 3-minute intervals don’t, even if the total time equals 20 minutes. The sustained stimulus is what triggers the specific biochemical cascade.

What This Looks Like in Practice for an experienced varsity high school runner:

Week 4-5 (threshold introduction):

- Monday: 6 miles easy + drills

- Tuesday: 2 mile warm-up, 3×8 minutes at threshold (2 min recovery), 2 mile cool-down

- Wednesday: 5 miles easy

- Thursday: 7 miles with 5 miles at “steady” effort (marathon pace, conversational)

- Friday: 4 miles easy

- Saturday: 12 mile long run with final 3 miles at steady

- Sunday: Off

Week 6-7 (threshold progression):

- Tuesday: 2 mile warm-up, 2×12 minutes at threshold (2 min recovery), 2 mile cool-down

- Thursday: 2 mile warm-up, 20-25 minute continuous tempo, 2 mile cool-down

- Saturday: 12-13 mile long run with middle 6-8 miles at marathon/steady effort

Total volume: 45-50 miles, with 15-20% at threshold intensity

The key progression: volume increases slightly, but more importantly, the duration of sustained threshold efforts extends from 8 minutes to 20+ minutes. This progressive overload is what forces adaptation.

Critical Coaching Detail: Christensen warns against the common error of running threshold work too hard. Threshold is controlled discomfort—you should be able to speak in short sentences. If you’re gasping for air, you’ve drifted into VO2max territory and you’re training a different system. High school athletes almost always err toward running too hard, which creates excess fatigue without the targeted adaptation. I implemented a rule that translated seconds, too fast or too slow, into pushups last XC season and it seemed to dial them in quickly.

Real World Example: Fayetteville-Manlius (New York), one of the most successful high school programs ever, built their dynasty on systematic threshold work. Coach Bill Aris doesn’t chase flashy VO2max intervals early season. He spends weeks developing threshold through “stomp” runs—sustained, controlled hard efforts that build the lactate clearance capacity to run 16-minute 5Ks without exploding. Their mid-season training blocks look repetitive by design—Tuesday tempo, Thursday tempo, Saturday long run with tempo segments. Week after week. It works because the repetition creates the adaptation.

Mesocycle 3: VO2max and Race Specific Development (Weeks 8-10)

Physiological Goal: Maximize oxygen uptake, improve running economy, develop neuromuscular power at race pace, sharpen mental race execution.

The Science: VO2max intervals—running at 95-100% max heart rate, roughly 3K-5K race pace—create adaptations that threshold work doesn’t touch. Magness details how these efforts increase stroke volume (the amount of blood pumped per heartbeat), enhance oxygen extraction in muscles, and improve running economy through neuromuscular coordination at speed.

Research shows that VO2max improvements happen in the 3-8 minute range of intense effort. Shorter sprints don’t sustain the stimulus long enough. Longer efforts drift below the target intensity. The sweet spot is 3-5 minute intervals with equal or slightly shorter recovery.

Critically, this phase builds on the previous mesocycles. Without the aerobic base from phase 1, you can’t recover between intervals. Without the threshold development from phase 2, you can’t hold the target pace long enough to create adaptation. Christensen calls this “training residuals“—earlier adaptations don’t disappear, they become the foundation that allows you to train harder in subsequent phases.

What This Looks Like in Practice for an experienced varsity high school runner:

Week 8 (VO2max introduction):

- Monday: 5 miles easy + drills and strides

- Tuesday: 2 mile warm-up, 6x800m at 5K goal pace (2-3 min recovery), 2 mile cool-down

- Wednesday: 5 miles easy

- Thursday: 7 miles steady

- Friday: 4 miles easy + strides

- Saturday: 10-11 mile long run

- Sunday: Off

Week 9-10 (race-specific progression):

- Tuesday: 2 mile warm-up, 5x1000m at 5K goal pace (2 min recovery), 2 mile cool-down

- OR: 2 mile warm-up, 3×1 mile at 5K pace (3 min recovery), 2 mile cool-down

- Thursday: 6 miles easy with 6x200m at mile race pace

- Saturday: 8-9 mile progression run (start easy, last 2-3 miles at tempo/threshold)

Total volume: 40-45 miles (volume decreases slightly as intensity increases)

Notice the progression: 800s progress to 1000s progress to miles, all at target 5K pace. Recovery stays relatively constant, which means work intervals get harder. The athlete develops the specific fitness to hold goal pace for progressively longer durations.

Race Integration: During this mesocycle, many programs race every weekend. Christensen advocates treating these races as hard workouts, not taper-and-peak performances. A Saturday race replaces the Tuesday VO2max workout. This allows athletes to develop racing skills—pack running, surging, mental toughness—while maintaining training load.

Real World Example: Loudoun Valley High School (Virginia) runs one of the more intelligent race-as-workout programs I’ve studied. During their pre-championship phase, they race hard on Saturday, treating it as the interval session. Tuesday is tempo work. Thursday is easy with strides. They don’t taper for these weekly races—kids might run 6 miles easy that morning before an afternoon invitational. By championship season, their athletes have race-specific fitness and mental toughness that crushes competitors who peaked in September.

Mesocycle 4: Competition and Taper (Weeks 11-12)

Physiological Goal: Achieve peak neuromuscular sharpness, shed accumulated fatigue while maintaining fitness, execute race performance.

The Science: This is controversial topic. And, honestly, this is where many coaches screw up. They either overtaper (reducing volume and intensity too much, too early) or undertaper (maintaining volume right up to championship day). Both kill performance.

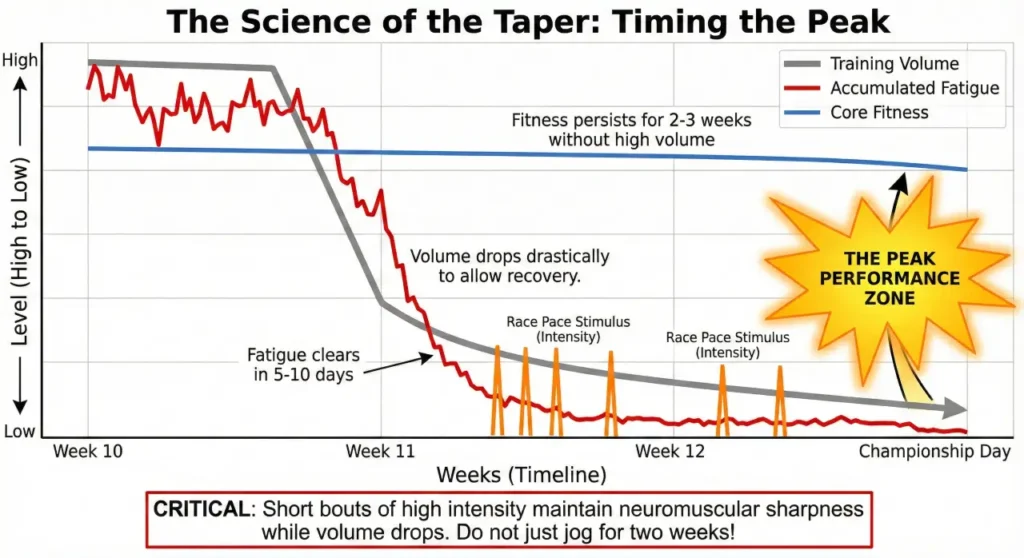

Magness cites research showing that fitness adaptations persist for 2-3 weeks without stimulus, but fatigue dissipates in 5-10 days. The taper exploits this gap. You reduce training stress enough for fatigue to clear, but not so much that fitness decays.

The taper should reduce volume by 30-40% while maintaining intensity. Christensen emphasizes that “you can’t gain fitness during taper week, but you can absolutely lose sharpness by going too easy.” The neuromuscular system—the connection between brain and muscles that allows you to run fast efficiently—degrades rapidly without race-pace stimulus.

What This Looks Like in Practice for an experienced varsity high school runner:

Week 11 (taper week 1):

- Monday: 5 miles easy

- Tuesday: 2 mile warm-up, 3x1200m at 5K pace (2 min recovery), 2 mile cool-down

- Wednesday: 4 miles easy

- Thursday: 5 miles easy with 4x200m at mile pace

- Friday: 3 miles easy

- Saturday: Race (regional championship)

- Sunday: 3-4 miles easy

Week 12 (championship week):

- Monday: 4 miles easy

- Tuesday: 2 mile warm-up, 3x800m at 5K pace (full recovery), 2 mile cool-down

- Wednesday: 3 miles easy + strides

- Thursday: 20-25 minute easy shakeout + 4x100m relaxed strides

- Friday: 15 minute very easy jog or off

- Saturday: Championship race

- Sunday: Celebrate

Total volume drops from 45-50 miles to 30-35 in week 11, then to 20-25 in week 12. But notice—you’re still touching race pace multiple times. You’re maintaining the neuromuscular patterns that allow you to run fast, just with massively reduced volume and stress.

Real World Example: Watching Newbury Park High School (California) taper is instructive. They run a hard workout the Tuesday before state finals—6x800m at race pace. Sounds crazy until you understand the science. That workout maintains sharpness without creating significant fatigue 10 days out. By race day, legs are fresh but the body remembers how to hurt. They’ve won multiple national championships using this approach.

The Art of Mesocycle Transitions

The most overlooked aspect of periodization? The transitions between mesocycles. Christensen warns that abrupt changes in training stimulus create breakdown rather than breakthrough.

Moving from base phase to threshold phase shouldn’t mean going from 45 miles of easy running to 45 miles with suddenly 10 miles of hard tempo work. The transition week (week 3-4 junction) should introduce threshold work gradually—maybe 3×6 minutes at threshold with generous recovery. Volume holds or drops slightly. You’re cueing the body: “New stimulus incoming, adapt accordingly.”

Think of mesocycle transitions like shifting gears in a car. Smooth transitions maintain momentum. Grinding gears destroys the transmission and stalls progress.

Programming Concurrent Qualities: The Weekly Microcycle

Within each mesocycle, the weekly structure—the microcycle—determines whether you’re maximizing adaptation or piling stress randomly. The research is clear: hard days should be hard, easy days should be easy, and the sequence matters.

Magness advocates for the “hard-easy-hard-easy” framework with intelligent spacing:

The Standard Microcycle:

- Monday: Recovery/Easy

- Tuesday: Primary workout

- Wednesday: Easy

- Thursday: Secondary workout (speed if Tuesday was threshold, tempo if Tuesday was VO2max)

- Friday: Easy

- Saturday: Long run or race

- Sunday: Off

This pattern creates 48-72 hours between hard sessions—the minimum required for physiological recovery and adaptation.

The mistake many high school programs make? They run “medium-hard” every day. Monday is 6 miles at “comfortable” pace. Tuesday is a tempo run. Wednesday is 7 miles at “steady” pace. Thursday is interval work. Friday is 5 miles at “moderate” pace. Saturday is a race. Nothing is easy enough to recover. Nothing is hard enough to create overload. The athletes exist in perpetual medium fatigue, never adapting optimally.

Adjusting Periodization for Individual Variables

The periodization model I’ve outlined is a framework, not a prescription. Individual variation demands individual adjustment.

Training Age: Freshmen with six months of running can’t handle the same mesocycle structure as seniors with four years of base. The freshman might need to extend general prep to 4-5 weeks, barely touch VO2max work, and never exceed 30 miles weekly.

Athlete Type: Some runners are volume responders—their fitness correlates directly with mileage. Others are intensity responders—they thrive on harder workouts with less overall volume. A coach can discover this through careful observation across seasons. The volume responder might run 50 miles weekly during specific prep; the intensity responder peaks at 30 but hammers workouts harder.

Multi-Sport Athletes: The soccer player joining for track season in March skips general prep entirely—they have an aerobic base from soccer. They need accelerated threshold development (2 weeks instead of 4) before jumping into race-specific work. The periodization timeline compresses but the sequence stays intact.

Recovery Capacity: The athlete who bounces back in 24 hours can handle three hard sessions weekly. The athlete who needs 72 hours gets two. Both can succeed, but their microcycles look different.

Monitoring and Adjusting: The Feedback Loop

Smart coaches build feedback mechanisms to know when adjustments are needed.

Performance Markers: Are athletes hitting workout targets? If your runners can’t complete the prescribed 6x800m at goal pace by week 9, either the goal pace is wrong or the preceding mesocycles didn’t create the necessary adaptation. Go back and repeat the previous week(s).

Subjective Wellness: Monitor sleep quality, mood, muscle soreness, and motivation. When multiple athletes report poor sleep and flat motivation for three consecutive days, that’s not mental weakness—it’s physiological distress signaling. Dial back intensity for 3-4 days and reassess.

Injury Patterns: If multiple runners develop the same injury during a specific mesocycle, that’s not bad luck—it’s a programming error. Shin splints epidemic during week 4-5? The volume jumped too aggressively entering threshold phase. Achilles issues in week 9? The shift to VO2max work lacked adequate transition. Periodization should prevent injury patterns, not create them.

Race Results: Are athletes racing faster as the season progresses? A properly periodized season sees progressive improvement—slower early-season races, significant drops mid-season as fitness builds, peak performances at championships. If your fastest races happen in September, your periodization is backwards.

The Mental Periodization Nobody Discusses

Physical periodization gets all the attention, but psychological periodization is equally critical for high school athletes.

Early season (general prep) should feel relaxed—building fitness without pressure. This is when athletes rediscover their love for running after summer break, when team bonds form on easy long runs. Workouts are conversational. Races should be low-key events.

Mid-season (specific prep) introduces controlled stress—workouts are harder, expectations rise, but the championship is still distant. Athletes develop mental toughness through challenging threshold work and weekly competitions. They learn to suffer productively.

Late season (pre-competition and taper) is when intensity peaks both physically and psychologically. Every workout matters. Racing is high-stakes. The team-focused mindset shifts toward individual peak performance.

If you flip this—demanding championship-level intensity in week 2, or keeping things casual in week 11—you’ll break athletes mentally before the racing ever breaks them physically.

To see how these mesocycles fit together in a real season, view this 13-week Championship Season Case Study.